Journal of Financial Planning; November 2014

Jarrod Johnston, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor of finance at Appalachian State University where he teaches courses in finance and retirement planning.

Ivan Roten, Ph.D., CFP®, is an associate professor of finance in the department of finance, banking, and insurance at Appalachian State University.

Executive Summary

- This paper examines various scenarios to illustrate when 401(k) loans are advisable and when they are a poor choice.

- Loans from 401(k) plans represent a trade-off between the interest rate that would be paid on a bank loan and the return expected to be earned on the 401(k) investments. A 401(k) loan is preferable only if the interest rate exceeds the expected return of the 401(k) investments.

- Origination and maintenance fees combined with small loan amounts dramatically increase the cost of 401(k) loans. Borrowers may reduce their deferral rate to offset loan payments. Tax consequences in the event of default, usually due to job loss, and bankruptcy protection may also diminish the appeal of 401(k) loans.

- Loans taken from 401(k) plans are preferable when used as an alternative to high-interest rate debt. Loans are also preferable when expected investment returns are low. Individuals with low-rate fixed-income 401(k) investments may be better off lending that money to themselves through a 401(k) loan.

Many 401(k) plans offer participants the option to borrow from their own accounts. Details and restrictions vary across plans, but generally the minimum amount is $1,000 with the maximum amount being the lesser of $50,000 or 50 percent of the vested account balance. Loans are amortized and the maximum length is five years.1 The employer may also restrict the number of loans outstanding and the reasons for borrowing. Legally, a plan that offers loans must make them available to all participants and must apply any restrictions uniformly.

The average 401(k) loan size is roughly $7,000 and has been slowly rising since 1998, according to data from the Employee Benefit Research Institute. As shown in Figure 1, among individuals with access to 401(k) loans, about 20 percent had loans outstanding in 2011. The outstanding loan balance was nearly 15 percent of 401(k) assets. Although the percentages have been mostly steady, the overall amounts have been rising as total 401(k) assets increase.

The convenience of 401(k) loans has increased their popularity. Typically, borrowers complete a brief application while at work and receive the funds within a few days. Most plans allow borrowing for any reason and do not require a credit check. Loan payments are usually set up by the employer and deducted from the borrower’s paycheck.

Other factors are more important in determining the prudence of borrowing from a 401(k). Proponents of 401(k) loans argue that borrowing from yourself and paying interest back into your account is better than paying interest to a bank or other financial institution. Although this sounds appealing, a 401(k) loan that returns 6 percent to a borrower’s account is a poor choice if the borrower’s account would otherwise earn 14 percent. Leaving money in the 401(k) and borrowing from an outside source will increase the wealth of the participant. However, 401(k) loans may be good alternatives for borrowers who have poor credit or are liquidity constrained. This is primarily due to the high interest rates the participant would otherwise pay (Tang and Lu 2014).

Li and Smith (2008) and Lu and Mitchell (2010) found that liquidity constrained households are more likely to take 401(k) loans. However, Li and Smith (2008) also noted that 401(k) borrowing has been increasing among households that are not liquidity constrained. This suggests that 401(k) loans are more likely to be considered a credit option for all eligible participants, not just the liquidity constrained.

It’s important to note that, in general, competitive interest rates and the tax deductibility of home equity loans make these tools a better alternative to 401(k) loans. Interest rates on home equity and 401(k) loans are typically 1 to 2 percent above the prime rate. If a borrower is eligible for the tax deduction of a home equity loan, the rate of the home equity loan will be lower than that of a 401(k) loan. The home equity loan provides additional savings to the borrower compared to the 401(k) loan.

The main argument against borrowing from a 401(k) is lost investment return. The money borrowed is paid back with a fixed amount of interest rather than a potentially higher return from stock and bond investments. Detractors also argue that 401(k) loan payments are double taxed because they are paid with after-tax dollars. Although this is technically true for the interest payments on 401(k) loans, this argument is nonetheless irrelevant. Loans are paid with after-tax dollars regardless of whether they are 401(k) loans or bank loans (mortgage and home equity loans are exceptions). Similarly, earnings in a 401(k) are taxed at withdrawal regardless of whether the earnings are from investments in stocks or bonds or from a loan to the account holder (earnings are not taxed with Roth 401(k)s).

The relevant issue is the wealth difference at the end of the loan. Beshears, Choi, Laibson, and Madrian (2008) showed that the effect of 401(k) loans on asset accumulation is minimal. They also concluded that 401(k) loans are a reasonable source of credit when the borrower is liquidity constrained.

A final argument against 401(k) loans is that they are used to increase consumption rather than to provide an alternative for other debt. Beshears, Choi, Laibson, and Madrian (2011), using annual data from The Survey of Consumer Finances, found in various years that up to 33 percent borrow from their 401(k) to purchase or improve a home; up to 23 percent purchase a vehicle or other durable good, and up to 16 percent pay for education or medical expenses. Utkus and Young (2010) showed that younger, less educated, and poorer individuals were more likely to borrow from their 401(k). Li and Smith (2008) found that many households with high interest rate credit card debt do not borrow from their loan-eligible 401(k). Borrowing to retire high-rate credit card debt that was incurred due to an unfortunate event is likely to be a prudent decision. However, if credit card debt is due to poor decisions or reckless spending, financial counseling is often needed to ensure the borrower will make better decisions in the future. A borrower who continues to use credit cards irresponsibly after borrowing to pay them off will be in worse financial condition.

We present findings that the interest rate and the investment return are the most important factors influencing the 401(k) loan choice. The relevant interest rate is the rate that would be paid if a 401(k) loan was not used. The rate of a 401(k) loan is typically lower than the rate of similar loans. The difference in payments provides savings to the borrower. The choice for the borrower is whether the investment return is expected to be higher than the lowest available market rate. If the investment return is expected to be higher, a 401(k) loan is a poor choice.

Although the interest rate and the investment return are the most important factors, other variables can dramatically reduce the benefits of 401(k) loans. Origination fees, maintenance fees, size of the loan, and the return on savings are relevant factors that need to be considered. Table 1 summarizes the conditions that indicate whether a 401(k) loan is appropriate.

Scenario Analysis

The following analysis examines whether the decision to borrow from a 401(k) is better than borrowing from a bank or other financial institution at market rates. It is assumed that there is a need to borrow money. The possibilities include auto loans, other unavoidable expenses, and paying off credit card or other high interest-rate debt.

The analysis begins with assumptions favorable to 401(k) loans. The model uses four factors: (1) the 401(k) loan rate; (2) the bank loan rate; (3) the marginal tax rate; and (4) the investment return or the return for money invested in the 401(k). The following assumptions were made in the analysis:

- Five-year amortized loan with monthly payments

- Investment returns are compounded monthly

- A marginal tax rate of 20 percent

- No transaction fees

- The difference between the 401(k) loan payment and the bank loan payment increases or decreases the 401(k) balance

For example, assume an individual needs a $20,000 loan. The loan can come from the individual’s 401(k) at 5 percent or from a bank at 7 percent. The monthly payments on the 401(k) loan and the bank loan are $377 and $396, respectively. The $19 difference is equivalent to $23 on a before-tax basis and is added to the 401(k). Assuming an 8 percent monthly compounded investment return, the 401(k) loan payments and the additional contributions equal $29,440 at the end of five years. If the loan is taken from a bank, the $20,000 that remains in the 401(k) grows to $29,797 at the end of five years. The account balance is $357 lower if the loan is taken from the 401(k). There is no difference between the two options when the 401(k) investment return is 7.5 percent. When the investment return is greater than 7.5 percent, a bank loan is the best option. Conversely, if the investment return is less than 7.5 percent, a 401(k) loan is preferable.

The break-even investment return for different assumptions is shown in Table 2. If the investment return is expected to be less than the break-even investment return, a 401(k) loan is preferable. Otherwise, a bank loan is preferable. The break-even investment return is a function of the bank loan rate, the difference between the bank loan rate and the 401(k) loan rate, and the tax rate. As the differential between interest rates rise, the break-even investment return rises above the bank loan rate.

Similarly, the break-even investment return rises when the tax rate increases.2

The initial scenario assumptions are favorable to 401(k) loans. The use of more realistic assumptions decreases the appeal of 401(k) loans. If the payment difference is deposited into an after-tax savings account instead of being contributed to a 401(k), the break-even investment return declines to slightly below the bank rate. For example, if the 401(k) rate is 5 percent, the market rate is 7 percent, and the savings rate is 1.5 percent, the break-even investment return falls from 7.5 percent to 6.8 percent.

The analysis changes if the interest rate available on a 401(k) loan is 4.25 percent, the savings rate is 0.65 percent, the marginal tax rate is 20 percent, and the interest rate on a personal loan is 11.25 percent. The break-even investment return in this example is between 10 percent and 13 percent, depending on additional assumptions. The 401(k) loan is preferable unless the expected return on investments in the 401(k) is greater than 10 percent to 13 percent.

Historical Analysis

The following analysis shows account balances at the end of the five years being determined for various loans compared with the account balances for 401(k) loans taken at the same time. In addition to the previous assumptions, the 401(k) loan rate was assumed to be the prime rate plus 1 percent. The investment return was calculated using the S&P 500 Index. Rates for auto loans, personal loans, and credit cards were used for comparison. The data were obtained from the Federal Reserve Economic Database at the St. Louis Federal Reserve site (research.stlouisfed.org/fred2).

The ending 401(k) account balance for $20,000 invested in the S&P 500 for five years was calculated, as was the ending 401(k) account balance for a $20,000 loan to the participant for five years. Loan payments and the difference in payments were assumed to be invested in the S&P 500. The analysis began in January 1980, and the first account balance comparison was January 1985. Account balances were calculated each year beginning in January from 1985 through 2013. Rates for auto loans, personal loans, and credit cards were used for comparison. Credit card data begin in 1994. The average for the calculation is from 1999 to 2013. The average account balance is reported in Table 3.

The data include the high interest rate environment of the early 1980s, when the prime rate reached 20 percent. The average 401(k) balance is $615 higher if the loan is taken from a 401(k) compared to an auto loan. The 401(k) loan advantage increases with higher rate loans. Historically, 401(k) loans have been a reasonable lending choice. This is particularly true in high interest rate environments and in comparison to relatively high interest rate loans. When data from the 1980s are excluded, the results are mixed. Auto and personal loans are better alternatives to 401(k) loans.

Fees and Expenses

Another assumption that favors 401(k) loans is the absence of fees. However, many 401(k) plans charge origination and quarterly maintenance fees, whereas bank loans typically do not. This combination typically decreases the appeal of 401(k) loans. In particular, these fees dramatically increase the cost of small 401(k) loans.

The effect of fees on the break-even investment return is presented in Table 4. A $20,000 loan with a market rate of 7 percent has a 7.5 percent break-even investment return when the difference is contributed to a 401(k). The break-even falls to 6.8 percent when the difference is invested in a savings account. If a $75 origination fee and a $35 annual maintenance fee are included, the break-even falls to 6.3 percent. Drop the loan amount to $2,000 and the break-even falls to 2.4 percent. A combination of 401(k) loan fees and small loan size dramatically reduces the appeal of 401(k) loans.3

Other Considerations

Deciding whether to obtain a 401(k) loan involves a review of several other advantages and drawbacks associated with these loans.4 First, there is no credit check with 401(k) loans, making them more attractive to individuals with poor credit. Additionally, individuals with poor credit are typically charged higher interest rates when applying for a traditional loan; this is not the case with a 401(k) loan. Another advantage to 401(k) loans is the ease of use. Generally, a short form is submitted to the employer and loan payments are deducted from the borrower’s paycheck.

A significant disadvantage is that if a 401(k) loan is not paid back, the outstanding amount is reported to the Internal Revenue Service as a distribution and the borrower must pay ordinary income tax plus a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty if the borrower is younger than age 59½. The possibility of default increases in the event of job loss. A loan from a 401(k) must be repaid in full within 90 days after employment ends, or the loan is in default. Also, assets in retirement plans are protected in bankruptcy. Individuals who may face bankruptcy would not want to deplete protected assets. A 401(k) loan is a poor option for individuals facing a job loss or possible bankruptcy.

Conclusion

When borrowing is unavoidable, a 401(k) loan may be the most appropriate choice under three scenarios. First, if the only alternative is high interest rate debt, a 401(k) loan may be the best alternative. A return to a high interest rate environment similar to the early 1980s would make 401(k) loans more attractive to all eligible participants. Credit card or other high interest rate debt may make 401(k) loans attractive to individuals saddled with these kinds of debt. Second, a 401(k) loan may be preferable if expected investment returns are low. For instance, an individual with low-rate fixed income investments in his or her 401(k) may be better off lending the money to himself/herself through a 401(k) loan. Third, the 401(k) loan may be the only option for those who have poor credit or those who are liquidity constrained.

A 401(k) loan is not a good choice under numerous scenarios. The current low interest rate environment makes 401(k) loans less attractive. Additionally, having good credit and access to home equity loans allow many to borrow at low rates that make 401(k) loans less competitive. A 401(k) loan is a poor choice if other low-rate debt is available. A 401(k) loan is also a problematic choice when origination and maintenance fees are required and the amount to be borrowed is small. Finally, borrowing outside of a 401(k) plan is preferable when investment returns are expected to be high or when borrowers may lose their jobs or file bankruptcy.

Endnotes

1. Loans to purchase a home may exceed five years.

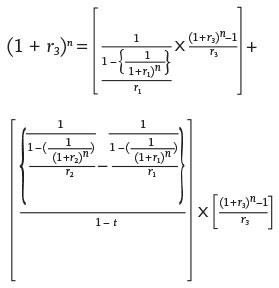

2. The equation to determine the break-even investment return is: Edit media

where r1 is the 401(k) loan rate, r2 is the bank loan rate, r3 is the break-even investment return, n is the number of periods, and t is the tax rate.

3. Loans from banks and other financial institutions may also include application or processing fees. Generally, personal loans do not have fees. Lines of credit have annual fees that range from $0 to $50. Auto loans have application or processing fees that range from $0 to $175. Credit cards often have annual fees of $50 or less. Fees make these loans more expensive and increase the appeal of 401(k) loans.

4. Although this analysis deals with 401(k) plans, it is important to note that salary deferral plans similar to 401(k) plans, such as 403(b) plans, may have different loan provisions that make them a poor alternative. Often, 403(b) plans require the participant to borrow from the financial institution that is the record keeper rather than from the participant’s own account. They also typically require that the amount of the loan be invested in a fixed-income investment while paying back the loan to the institution at a higher rate. For example, an individual who takes a $20,000 loan from her 403(b) plan must have $20,000 in her account invested in a guaranteed or other fixed-income investment while taking the loan from the provider at some higher rate. In this case, the 403(b) participant essentially pays a 2 percent premium to borrow her own money.

References

Beshears, John, James Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte Madrian. 2008. “Financial Liquidity and Saving: Evidence from 401(k) Loans.” Harvard University and National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

Beshears, John, James Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte Madrian. 2011. “The Availability and Utilization of 401(k) Loans.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper: Investigations in the Economics of Aging.

Li, Geng, and Paul Smith. 2008. “Borrowing from Yourself: 401(k) Loans and Household Balance Sheets.” Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Vol. 2008–42, Federal Reserve Board.

Lu, Timothy, and Olivia Mitchell. 2010. “Borrowing from Yourself: The Determinants of 401(k) Loan Patterns.” Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper No. 2010.

Tang, Ning, and Timothy Lu. 2014. “Are Your Clients Making the Right Loan Choice?” Journal of Financial Planning 27: (10) 39–47.

Utkus, Stephen P., and Jean Young. 2010. “Financial Literacy and 401(k) Loans.” Pension Research Council Working Paper No. 2010–28.

Citation

Johnston, Jarrod, and Ivan Roten. 2014. “Benefits and Drawbacks of 401(k) Loans in a Low Interest Rate Environment.” Journal of Financial Planning 27: (11) 40–44.