Journal of Financial Planning: September 2011

David M. Blanchett, CFP®, CLU, AIFA®, QPA, CFA, is the director of consulting and investment research for the Retirement Plan Consulting Group at Unified Trust Company in Lexington, Kentucky.

Executive Summary

- The widespread acceptance of target-date portfolios has improved participant investing. More participants are deciding to let investment professionals manage their accounts and will likely achieve higher returns and less risk as a result.

- Unfortunately, target-date portfolios, in particular target-date funds, are widely misused and are not properly understood by 401(k) plan participants. Because of this, target-date funds are likely only a temporary solution to the permanent problem of 401(k) plan participant self-direction.

- This paper will introduce an automatic managed account solution designed to be a permanent asset allocation solution for 401(k) plan participants.

- Initial evidence suggests professionally managed portfolios designed in a way to maximize participant use have advice-acceptance rates of more than 80 percent and dramatically improve the probability of 401(k) plan participants accumulating enough assets to fund retirement income.

The age of target-date portfolios is well upon us. Target-date portfolios, especially target-date mutual funds, have exploded in popularity since the introduction of the Pension Protection Act (PPA), signed into law on August 17, 2006, by President George W. Bush. Defined-contribution plan fiduciaries, whether they are members of the plan oversight committee or are plan consultants, likely already have addressed the suitability of target-date funds for their plan or are going to in the near future.

Target-date investments are great, in theory, for improving participant investing. The notion that participants are poor investors (the permanent problem) has been well established; therefore, moving participants into a professionally managed investment holds great potential. Unfortunately, the realization of these benefits in the current target-date mutual fund environment has been questionable. For example, only 19 percent of participants in defined-contribution plans at Vanguard that have target-date mutual funds available are pure target-date investors who invest solely in a specific target-date fund (Vanguard 2010).

The true target of any participant-level investment policy should be to maximize the likelihood of retiring successfully (defined as replacing 70 percent of compensation during retirement including Social Security) with the least amount of risk, something target-date investments by their nature are unable to do. Although the one-size-fits-all approach in target-date investing is an improvement over participant-directed investing, target-date investing is by no means the optimal participant asset allocation solution. This paper suggests that another solution—correctly designed, professionally managed accounts—provides a better answer to the permanent problem of poor investing decisions commonly made by 401(k) plan participants. Initial evidence suggests professionally managed portfolios designed in a way to maximize participant use have adoption rates of more than 80 percent and dramatically improve the probability of 401(k) plan participants accumulating enough assets to fund retirement income.

Introducing Qualified Default Investment Alternatives

The PPA introduced a variety of changes to defined-benefit and defined-

contribution plans, including qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs). QDIAs can be used as the default investment for participants who are automatically enrolled in a 401(k) plan but who did not affirmatively elect a particular investment. Before the introduction of the PPA, there was no “safe harbor” for the default investment choice and therefore no ERISA §404(c) relief for plan sponsors.1 This led to the widespread use of conservative investment options, such as money market or stable value funds, as the default in the absence of a participant election. Although money market and stable value funds offer capital conservation, they are not necessarily prudent long-term investment solutions for 401(k) plan participants, and therefore do not qualify as QDIAs for purposes of §404(c)(5).

The PPA introduced three types of QDIAs: risk-based investments, target-date investments, and professionally managed portfolios. Among the three options, target-date investments (also referred to as life-cycle investments) have become the overwhelming favorites. According to the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging (2009), 96 percent of plans that offer the automatic enrollment feature are using target-date funds as the default investment. In terms of overall adoption, as of 2009, 75 percent of plans with assets over $200 million were using target-date portfolios, 66 percent of plans with assets between $5 million and $200 million were using target-date portfolios, and 50 percent of plans with assets below $5 million were using target-date portfolios (Janus and Brightwork Partners 2009).

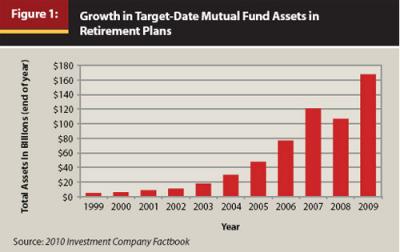

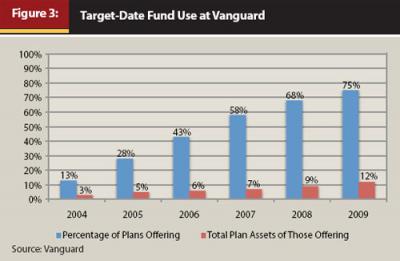

Vanguard, the second-largest retirement plan provider in the United States by assets, has seen a dramatic increase in its defined-contribution plans offering target-date funds. In 2004 only 13 percent of its plans had target-date funds, which increased to 75 percent by 2009. Vanguard’s experience with increasing 401(k) plan use of target-date funds mirrors that of the 401(k) plan industry, with the number of assets in target-date portfolios exploding as more plan sponsors introduce them to their 401(k) plans. Figure 1 shows the growth in total assets in target-date mutual funds in 401(k) plans from 1999 to 2009.

Participant Investing: The Permanent Problem

In theory, the widespread use of target-date funds (or really any professionally managed portfolio) holds great promise. This is because most people, 401(k) plan participants included, are notoriously bad investors. Studies have consistently documented this; see for example Kasten (2005) or Munnell et al. (2006). These poor decisions are limited not only to fund selection but also to asset allocation decisions.

From a fund selection perspective, Frazzini and Lamont (2008) have noted that mutual fund flows tend to be “dumb money,” whereby reallocating across different mutual funds, retail investors tend to experience lower returns and reduce their wealth in the long run (for example, buying tech mutual funds in 1999). Fund investors tend to purchase funds that have outperformed their peers (chase returns), which subsequently underperform. In a separate analysis, Teo and Woo (2004) also find evidence to support the dumb money effect.

From an asset allocation perspective, Mottola and Utkus (2007) have provided one of the most robust studies about the asset allocation decisions of investors. They reviewed the allocations of approximately 2.9 million participants at Vanguard and found that only 43 percent of participants had “green” portfolios with balanced exposure to diversified equities. They noted that 26 percent of participants had “yellow” portfolios with possibly too-aggressive or too-conservative equity allocations, and 31 percent of participants had “red” portfolios with either no equities or too high a concentration of employer stock. The authors also noted that the cost associated with these poor asset allocation decisions is significant, reducing expected real returns by roughly 60 to 350 basis points per year.

Hewitt Associates and Financial Engines (2010) noted that the median annual return from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2008, for investors who received employer-provided help or advice (for example, use of a managed portfolio solution) was 186 basis points higher (after taking fees into account), on average, than the returns of those who did not receive any help. Although these findings are notable and consistent with past research on the benefits of professionally managed solutions, only 25.3 percent of the participants eligible to receive the advice in those plans chose to do so. Of the participants who did use advice, 9.8 percent used target-date funds, 9.7 percent used managed accounts, and 5.8 percent used online advice, according to the study. Therefore, although there clearly are benefits to following advice, most participants don’t actually obtain them because they don’t use the advice.

Attempting to educate participants to help them make better investing decisions has also yielded poor results. Most participants are simply not interested in learning about investing and financial markets (no more, for example, than is the author in learning how his car operates). When confronted with too many options, 401(k) plan participants experience something known as choice overload, and participation tends to decline. A commonly cited study regarding choice overload conducted by Iyengar, Jiang, and Huberman (2003) noted that participation in 401(k) plans dropped 2 percent for every 10 options offered in the plans surveyed.

What does appear to work is simplicity. A study by Citistreet in 2007 found that the fewer decisions employees need to make, the more likely they are to enroll in a 401(k) plan. The study noted that enrollment rates can be improved significantly by removing the investment decision making up front and by defaulting employees into an appropriate fund or portfolio. Once participants are enrolled, a second tier of communication can be used to help them, if desired, choose other appropriate investments for their savings goals. The key is to make the enrollment process as simple as possible.

Target-Date Funds: The Temporary Solution

The typical investment strategy of a target-date portfolio is relatively straightforward: as the portfolio approaches its target retirement date, the asset allocation becomes more conservative by reducing the equity exposure of the portfolio over time. For example, a target-date portfolio with 40 years until retirement may have an 80 percent allocation to equities that decreases to 40 percent as the portfolio approaches its retirement date. The lifetime equity exposure of a target-date portfolio is commonly referred to as its glide path. Glide paths can vary significantly across target-date providers. Figure 2 shows the range of equity allocations across target retirement years for target-date mutual funds.2

Selecting a target-date fund is usually intuitive for 401(k) plan participants, because they simply select the portfolio with the target retirement date that most closely matches their expected retirement date. Target-date funds also work well as default investments, because all plan sponsors need to know about a participant to default him or her into the appropriate target-date fund is the participant’s birth date and an assumed retirement age. The default procedure is generally outlined in the plan’s investment policy statement.

Target-date funds aren’t without their faults, though, as many plan sponsors, participants, and plan consultants have come to realize. Three key problems with target-date portfolios (in particular target-date mutual funds) are (1) their one-size-fits-all approach to risk (in which all participants have the same equity allocation based on expected retirement date), (2) their construction primarily from investments from the sponsoring mutual fund company, and (3) their use in combination with other plan investments.

Can you imagine walking into a doctor’s office and, after providing no other information than your birthday, having the doctor prescribe you a medication? A single glide path approach to target-date investing ignores the possibility of investors with varying risk preferences. There is such a thing as a conservative 30-year-old and an aggressive 60-year-old; yet in a single glide path environment, everyone the same age has the same equity allocation regardless of risk tolerance.

Although it is unlikely each participant will provide detailed information about his or her risk tolerance and risk capacity, it is possible to determine whether a participant is on track to retire successfully using a few data points available from the plan sponsor, such as the participant’s age, savings rate, compensation, and current total plan savings. Blanchett and Kasten (2010) suggest that dynamically updating a participant’s asset allocation based on his or her funded status leads not only to a higher probability of achieving retirement success but also to less account dispersion at retirement.

Most target-date portfolios, especially target-date mutual funds, are constructed entirely from mutual funds from the sponsoring organization. For example, the Fidelity Freedom 2030 Fund consists of 23 investments, each of which is a Fidelity mutual fund. Very few 401(k) plan core menus today feature investment menus from a single provider, so how can it be prudent that plan investments expected to receive a lion’s share of the money be invested entirely with a single company? A study by BrightScope found that target-date funds have internal fees between 10 percent and 25 percent more expensive than other funds offered on the core menu.

Finally, target-date mutual fund investors commonly combine the funds with other investments, effectively destroying the intended benefit of the target-date portfolio. Janus (2009) noted that 65 percent of 401(k) plan participants believe they need to combine a target-date fund with other funds in the plan in order to achieve the desired amount of income for retirement. Additionally, 63 percent of participants believe target-date funds need to be combined with other funds in order to achieve a diversified portfolio. Participants often fail to realize the diversification benefits of target-date funds, and instead tend to perceive them as “black boxes” they then combine with other investment options in the plan.

Given these attitudes, it is not surprising that target-date use has not been overwhelmingly positive. Vanguard has noted that only 41 percent of its participants use target-date funds when they are offered. Of those target-date fund participants, 54 percent are mixed investors, combining a target-date fund or funds with other fund options.3 Therefore, only 19 percent of participants who had access to target-date funds at Vanguard were using them correctly or were pure target-date investors (Vanguard 2010). Although the number of retirement plans adding target-date funds has increased at Vanguard, asset growth in target-date funds has not followed suit, as shown in Figure 3. It can also be inferred from Figure 3 that only 9 percent of Vanguard’s total retirement plan assets are currently invested in target-date funds.

The Target-Date Experience

Most participants’ experience using a target-date fund has been mixed at best. During the enrollment process, a participant will typically see a list of target-date funds included among a list of the other core menu investment options. Given this layout, target funds appear as black boxes, not as distinct total portfolio solutions. Therefore, it’s not surprising that most participants use them incorrectly, if at all. Although properly used target-date funds should serve as an entire investment solution for participants, they appear to be one of many potential options.

Additional participant confusion about target-date funds stems from how they operate. Janus and Brightwork Partners (2009) concluded that many participants do not sufficiently understand target-date funds or how to use them and that investor education about target-date funds has been inadequate and ineffective. The study notes that despite target-date fund holders’ general understanding of the target-date concept, participants are prone to misuse them and often harbor misperceptions about the specific objectives and attributes of the target-date portfolios.

Plan sponsors appear equally unsure when it comes to selecting target-date funds. The preamble to the QDIA regulation says, “A fiduciary must engage in an objective, thorough, and analytical process that involves consideration of the quality of competing providers and [QDIA] investment products, as appropriate.” Despite this guidance, the most important overall consideration when selecting a QDIA by sponsors was best overall performance, not more relevant attributes such as the equity glide path or fees, according to Janus and Brightwork Partners (2009). Plan sponsors also are not applying the same level of due diligence to target-date funds or holding them to the same standards as other funds in their investment menu, despite the fact they are significantly more complex from a selection and monitoring perspective.

Plan sponsors are becoming increasingly weary of target-date funds, likely because of poor participant use and the additional difficulties associated with selection and monitoring. A study by Janus and PLANSPONSOR (2010) noted a significant decrease in the percent of plan sponsors who believe target-date funds are the best QDIA for their participants, with balanced and target-risk funds gaining attention. In 2009, 56 percent of plan sponsors believed target-date portfolios were the best QDIAs for their plan, but in 2010 only 34 percent did. Only 51.7 percent of plan sponsors believe participants are using target-date funds correctly, and more than one-third of plan sponsors are unsure whether their recordkeeper is offering the most appropriate target-date funds available, according to the study.

The target-date mutual fund industry came under increasing scrutiny given the performance of target-date funds during the recent recession, especially during 2008. In 2008, the average return for mutual funds with a 2010 target retirement date was approximately –24 percent. The Oppenheimer Transition 2010 fund was down 41 percent, a dangerous drop given participants in the fund would be expected to retire in two years. Although the poor performance of target-date funds can likely be attributed to multiple factors, the internal competition to generate the highest return in the peer group led to increasing equity allocations that played a significant role in the poor performance.

In response to these events the U.S. Department of Labor has proposed new rules to enhance target-date retirement fund disclosures about the design and operation of target-date or similar investments, including an explanation of the investment’s asset allocation, how that allocation will change over time (with a graphic illustration), and the significance of the investment’s target date. Although these updates should provide participants more information about target-date funds, it is unlikely they will dramatically improve target-date fund investing behavior and use, given the framework in which they are traditionally offered.

The Permanent Solution … Is Automatic

So why aren’t target-date portfolios working? The fundamental theory on which they’re based is actually quite sound: automatically enroll participants in a professionally managed portfolio. Automatic enrollment works because people, 401(k) plan participants included, are prone to inertia. People tend to be lazy with matters they do not necessarily understand and too often just go with the flow. If the default (or easy) investment choice is a target-date portfolio, more participants are likely to use it than if they have to actively select it. Target-date use will also increase when participants believe the plan sponsor (potentially in conjunction with the plan consultant) has vetted the default option through implicit endorsement.

A key problem with the current enrollment process, though, is that most people don’t automatically enroll in their 401(k) plan; they actively participate in the enrollment process. They receive enrollment packets, forms, and other information that demands their time and involvement when it comes to determining allocations or selecting funds. Instead of asking participants how they would like to allocate the monies, a better approach would be to get information about each participant’s funded status (risk capacity) and risk tolerance. This information could then be used to determine how to invest the participant monies.

Granted, most participants won’t provide much information (if any), but enabling the participant to provide the 401(k) plan provider additional information can ensure the asset allocation assigned to that participant is far more meaningful than a single glide path. There will be some participants who will always want to opt out of any managed account platform and direct the investments themselves. Given the evolution of the 401(k) plan, taking away the ability to self-direct would likely be poorly received among participants, even though it is well within the right of the plan sponsor to do so.

Given the attributes and behaviors of 401(k) plan participants, especially as they relate to evidence regarding the use of target-date funds, the author contends there is a better approach to getting participants into a professionally managed portfolio. The ideal strategy not only maximizes professionally managed portfolio adoption by participants but also ensures the portfolio is suitable for each participant’s situation. This strategy would contain the following features:

- Enrollment in the managed account solution is automatic. No checking a box—just fill in your basic personal identification and beneficiary information (at a minimum) and you’re done.

- The portfolio assigned to the participant uses basic information already available to the 401(k) plan recordkeeper, such as age, compensation, savings rates, and total savings, to make general asset allocation decisions based on the funded status of the participant. Additional information can be provided by the participant, which would allow participants the chance to be engaged in the portfolio selection process by providing data about their unique situations and ensure the portfolio matches both their risk tolerance and risk capacity.

- The optimal portfolio dynamically updates through time based on the funded status of the participant. This prevents the initial allocation from becoming stale.

- The portfolio is built from the core menu funds and is presented as such. This would remove the black-box nature of target-date mutual funds.

- The solution is offered at no additional cost to the employee. Currently managed account platforms can cost anywhere between 10 bps and 75 bps. Additional cost is an obvious barrier to participant adoption. A lower fee assessed at the plan level also removes any prohibited transaction concerns with respect to using advice options as the default.

- The solution should be all or none; either you’re in or you’re out. Some participants will always want to direct their own accounts, and given the history of the 401(k) plan it is unlikely self-direction will disappear anytime soon. Multiple advice options could be offered, though—a variety of target-date portfolios with varying risk tolerances, along with risk-based portfolios.

Empirical evidence suggests introducing a managed account platform based on the above attributes as the default investment option can significantly improve retirement readiness for 401(k) plan participants. According to Kasten (2010), using a similar managed account solution led to advice acceptance of more than 90 percent. And combining the automatic portfolio solution with other automatic features such as automatic enrollment and progressive savings can lead to a 50 percent increase in the percentage of participants on track to retire successfully.

Conclusion

The widespread acceptance of target-date portfolios has improved participant investing. More participants are deciding to let investment professionals manage their accounts, and these participants will likely achieve higher returns and experience less risk as a result. Unfortunately, target-date portfolios, in particular target-date funds, are widely misused and are not properly understood by 401(k) plan participants. Because of this, target-date funds are likely only a temporary solution to the permanent problem of 401(k) plan participant self-direction.

The true target of any participant-level investment policy should be to maximize the likelihood of achieving the goal of funding retirement income with the least amount of risk, something target-date investments by their nature are unable to do. This paper introduced an automatic managed account solution designed as a permanent asset allocation solution for 401(k) plan participants. Initial evidence suggests professionally managed portfolios designed in a way to maximize participant use have advice acceptance rates of more than 90 percent and dramatically improve the probability of 401(k) plan participants being able to retire successfully.

Endnotes

- §404(c) is a defense for an allegation of imprudent investing at the participant level. In order to be compliant a number of conditions must be satisfied, one of which is that the participant—not the sponsor—had to have affirmatively made the investment election.

- Data were obtained from Morningstar as of December 31, 2009. For data integrity purposes all funds with equity allocations less than 20 percent were removed from the test population.

- Of the 54 percent “mixed” investors, only 3 percent were using combinations of only target-date funds; the other 97 percent were combining target-date funds with other investment options in the core menu.

References

Blanchett, David M., and Gregory W. Kasten. 2010. “Improving the ‘Target’ in Target-Date Investing.” Journal of Pension Benefits 18, 2 (Winter): 11–18.

BrightScope. “Real Facts About Target-Date Funds.” www.brightscope.com/media/docs/whitepapers/BrightScope-Real-Facts-about-Target-Date-Funds.pdf.

Citistreet press release. May 7, 2007. “Simple, Effective Communications Lead to Increased Plan Usage.” http://benefitslink.com/pr/detail.php?id=40628.

Frazzini, Andrea, and Owen Lamont. 2008. “Dumb Money: Mutual Fund Flows and the Cross-Section of Stock Returns.” Journal of Financial Economics 88, 2 (May): 299–322.

Hewitt Associates and Financial Engines. 2010. “Help in Defined Contribution Plans: Is It Working and for Whom?” http://corp.financialengines.com/employer/DCHelpReport_Jan2010.pdf.

Investment Company Institute. 2010. Investment Company Fact Book. 50th ed. www.ici.org/pdf/2010_factbook.pdf.

Iyengar, Sheena, Wei Jiang, and Gur Huberman. 2003. “How Much Choice Is Too Much? Contributions to 401(k) Retirement Plans.” Pension Research Council Working Paper 2003–10. www.archetype-advisors.com/Images/Archetype/Participation/how%20much%20is%20too%20much.pdf.

Janus white paper. 2009. “The Burden of Good Intentions: Opportunities and Challenges for Target-Date Funds.”

Janus and PLANSPONSOR. 2010. “Trends in Target-Date Funds.”

Kasten, Greg K. 2005. “Self-Directed Brokerage Accounts Tend to Reduce Retirement Success and May Not Decrease Plan Sponsor Liability.” Journal of Pension Benefits 12, 2 (Winter): 43–49.

Kasten, Greg K. 2010. “Increasing Retirement Success with the UnifiedPlan.” www.unifiedtrust.com/documents/UnifiedPlan IncreasesRetirementSuccess.pdf.

Mottola, Gary R., and Stephen P. Utkus. 2007. “Red, Yellow, and Green: A Taxonomy of 401(k) Portfolio Choices.” Pension Research Council Working Paper 2007–14. www.reish.com/publications/pdf/redyellowgreen.pdf.

Munnell, Alicia H., Mauricio Soto, Jerilyn Libby, and John Prinzivalli. 2006. “Investment Returns: Defined Benefit Versus 401(k) Plans.” Center for Retirement Research. www.imninc.com/Evergreen1/BC_Investment_Returns.pdf.

Teo, Melvyn, and Sung-Jun Woo. 2004. “Style Effects in the Cross-Section of Stock Returns.” Journal of Financial Economics 7: 367–398.

U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging. 2009. “Target Date Retirement Funds: Lack of Clarity Among Structures and Fees Raises Concerns” (October). http://aging.senate.gov/events/hr217cr.pdf.

Vanguard. 2010. How America Saves website. https://institutional.vanguard.com/VGApp/iip/site/institutional/marketing/How AmericaSaves.