Journal of Financial Planning: June 2020

Executive Summary

- College costs are increasing, and most students need to save or borrow to pay for education. Outstanding parental debt may affect the decision about how to fund their children’s education.

- The purpose of this research is to investigate whether parents’ own student loan balances affect their decision to save for their child(ren)’s college education via tax-advantaged education saving vehicles and if their debt affects their decision to take out loans on behalf of their child(ren) for educational purposes.

- According to this study, parents who are paying off their own student loan debt are less likely to invest in tax-advantaged accounts for their children’s education.

- For financial planners, this research highlights the importance of advising parents who may have their own student loan debt to start saving in tax-advantaged vehicles early.

Terrance K. Martin Jr., Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the Woodbury School of Business at Utah Valley University. He is also the founder of Tranquility Financial Planning and a professional speaker. His research interests include the value of financial advice and financial education.

Lua A.V. Augustin, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the Eberly College of Business at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests include financial literacy and credit management.

Laura C. Ricaldi, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the Woodbury School of Business at Utah Valley University. She also works as an associate adviser for GRID202 Partners, a financial planning firm consisting of multi-credentialed advisers committed to helping diverse clients. Her research interests are consumer loans, credit card borrowing, and materialism.

Jose Nunez is a research associate for Tranquility Financial Planning. He is an honors graduate of The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

One of the best investments an individual can make is earning a college degree. Having a college degree may provide greater stability for starting a family; it allows an individual to have better job opportunities with higher pay; and it provides better job security in volatile markets. In 2018, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics analyzed the earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment. Of those above age 25, people with a high school diploma had an unemployment rate of 4.1 percent, whereas people with a bachelor’s degree had an unemployment rate of 2.8 percent. The median weekly earnings for people with only a high school diploma were $730, and $1,198 for people with a bachelor’s degree, for an annual difference totaling $24,336.1

College costs are increasing (Carnevale and Strohl 2013). Paulsen and St. John (2002) noted that governments are placing more of the burden of financing college education on families and individuals. Student loans are replacing grants as the primary source of education financing; tuition rates continuously rise as a result of the decline of state funding for colleges. And student loan debt is increasing due to the greater costs of higher education (Belfield, Britton, Dearden, Van Der Erve 2017).

Rising college costs have affected students in other ways, such as having poor academic attainment, below-average performance, lower expectations, and lower college enrollment (Bennett, McCarty, and Carter 2015; Cappelli and Won 2016; Elliott and Beverly 2011). Even if a college education represents an opportunity for upward social mobility, this is not happening for students from low socioeconomic families and/or minorities who appear to have lower levels of educational attainment, lower GPAs, and lower academic aspirations. This is due to students having to work more and study less in order to afford their education (Walpole 2003; Bozick 2007).

Although Americans value college education, they may have a hard time estimating the cost of attendance (Horn, Chen, and Chapman 2003). Due to the complexity of the federal student aid system, many parents do not know the true costs of a college education and they overestimate the coverage of financial aid (Long and Riley 2007; Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2006). Parents either do not save enough due to miscalculation or simply are unable to save enough due to the high cost of attendance.

Most parents decide to save when their child is six years from entering college (McDonough and Calderone 2006). The majority claim they do not save earlier because they cannot afford it (Souleles 2000). Enabling parents to financially prepare for the child’s post-secondary education requires improving parents’ financial knowledge and access to these financial services (Johnson and Sherraden 2007). Parents often rely on college websites and counselors to supplement their financial knowledge; however, the quality of information varies and tends to be lower quality for those in lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2013).

Financing College Education: Saving Versus Borrowing

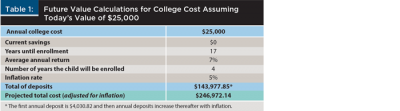

There is an economic benefit to build and use savings versus loans to pay for a child’s college education. First, by saving early the parent ends up paying significantly less for college because of the interest earned while saving. Parents who save 17 years before their child enrolls at a four-year college at a 7 percent average annual return will end up saving only 58 percent of the total college cost (see Table 1).

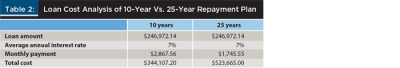

Second, the parent who borrows will not only pay the full price of college but also the interest on the loan. Assuming a 7 percent average annual interest on the loan, the parent with a 10-year repayment plan would pay 139 percent more than the parent who saved. The parent with a 25-year repayment plan would pay 264 percent more than the parent who decided to save (see Table 2).

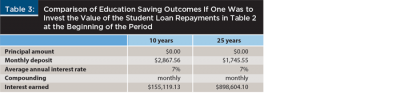

Third, the parent who services the loan is more restricted to investing money, thus experiencing an opportunity cost. If one takes the monthly payments of a 10-year repayment plan and of the 25-year repayment (see Table 2), and invests them instead at 7 percent compounded monthly, the parent with a 10-year repayment plan would forego $155,119.13, and the parent with a 25-year repayment plan would forego $898,604.10 (see Table 3). Based on these calculations, it is evident that saving for college is a better strategy than borrowing for college.

The purpose of this research is to investigate whether parents’ own student loan balances affect their decision to save for their child(ren)’s college education via tax-advantaged education saving vehicles and if they affect their decision to take out loans on behalf of their child(ren) for educational purposes.

Literature Review

A parent saving for their child’s college implies the parent has a plan for the future, and that he or she makes the child aware there are things needed to be done to attain higher education (Elliott 2009; Nam, Kim, Clancy, Zager, and Sherraden 2013). A parent can help finance the college education of their children by saving and/or taking out loans on behalf of their children—usually a Parent PLUS loan. When it comes to education saving, parents can use tax-advantaged vehicles such as the Coverdell education savings account (ESA) or the 529 plan. A student can finance their own college expenses through various methods such as grants, scholarships, work-study programs, and student loans.

Effect of student loans on earnings and net worth. Student loans may have negative consequences for individuals if not used properly. Students who graduate with student loan debt tend to have lower net earnings shortly after graduation in part because they are under pressure to pay off loans and accept the first paying job they’re offered (Gervais and Ziebarth 2019).

Rothstein and Rouse (2011) claimed that student loan debt may cause constraints to individuals such as preventing them from purchasing homes and/or preventing them from getting married. Elliott and Nam (2013) concluded that student loan debt can affect the short-run financial stability of households. Their analysis of 2007 to 2009 panel data from the Survey of Consumer Finances found that the median net worth for households who did not owe any loans in 2009 ($117,700) was higher than the median of households with outstanding student loan debt in that same year ($42,800).

Racial/ethnic gaps. Sometimes student loans can have negative consequences on students, even if the aim of student loans is to reduce the education inequalities among different racial/ethnical groups in society. For instance, Kim (2007) concluded that the increasing dependence of students on loans to finance their own education might contribute to the increase in the racial/ethnic gaps in obtaining a degree. By using a hierarchical linear model, Kim (2007) found that for blacks, the higher the loan amount, the lower the probability the borrower would complete a degree.

The consequences and behaviors associated with student loans seem to be different among the distinct races and ethnic groups. Cunningham and Santiago (2008) found that in the 2003– 2004 period, Asians and Hispanics had a lower probability of borrowing when compared to black and white students.

Jackson and Reynolds (2013) argued that even though student loans are achieving their goal of creating opportunities for students who could not otherwise attend or finish college, the goal of reducing educational inequality is not necessarily accomplished. They found that, for black students, loans promoted staying in school and created a higher probability of finishing it. However, this same study also found that black students usually had many outstanding loans, and when compared to white students, were more likely to default on their loan. Baker, Andrews, and McDaniel (2017) also found that black and Latino students had larger loan balances than their peers.

Kim (2004) found that when Asian-American students used only loans or a mixture of grants and loans, they were more likely to attend their first choice for college compared to white, African- American, and Hispanic students. Using data from The Freshmen Survey of 1994, Kim (2004) found that Asian-American students exhibited lower price sensitivity than the other groups. Therefore, the usage of loans allowed them to have access to their preferred college.

Effects of being debt averse. For some people, the thought of debt can deter them from seeking student loans. Negative attitudes toward debt appear to be increasing over time (Davies and Lea 1995; Baum and O’Malley 2003). Callender and Jackson (2005) found that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds had a higher fear of debt compared to their peers from high socioeconomic backgrounds, and students from the lower socioeconomic background tended to avoid taking on student debt because of this debt aversion. Even after controlling for other factors such as aspirations and encouragement, those from lower-income families were more averse to taking on student loans. Callender and Jackson (2005) also found that students from low socioeconomic backgrounds chose universities close to home in an attempt to reduce the level of student debt.

When borrowers drop out. One of the worst outcomes is when borrowers drop out of college before earning a degree. (Gladieux and Perna 2005; Callender and Jackson 2005). This outcome leaves the individual with the burden of debt and without higher earnings associated with obtaining a college degree, making it harder to pay off the debt. This usually causes the borrowers to default on their debt, which leads to bad credit.

Two important factors associated with college completion are the students’ living arrangements and work hours (Bozick 2007). Bozick (2007) used data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics from 1996 to 2001) to conclude that students living at home and working more than 20 hours a week were associated with higher dropout rates. Callender and Jackson (2005) found that lower-income students were more likely to live at home or close to home and were more likely to drop out as well. Light and Strayer (2000) used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth to explain the determinants of college completion and found that matching the school’s quality to the student’s ability gave the student a better chance of college completion.

Effects of household assets and liabilities. Zhan and Sherraden (2011) suggested a relationship between a household’s assets and liabilities and the expected educational levels for the household’s children. Household assets have a positive relationship to a child’s future college completion, while liabilities have a negative relationship.

Understanding defaults. In an attempt to determine student loan defaults, Flint (1997) found that a higher GPA was associated with lower default rates, and Dynarski (1994) found that minorities, low-income households, and two-year college students were more likely to default on student loans. Knapp and Seaks (1992) claimed that increasing retention programs in college would lower default rates because if the borrower graduated college, then he or she would earn a higher income and be more likely to pay off their student loan debt.

Volkwein, Szelest, Cabrera, and Napierski-Prancl (1998) used data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study to explore the factors that affected student loan defaulting among different racial/ethnic groups. By running logistic regressions, they found that Hispanics and blacks showed lower levels of degree completion and academic achievement when compared to whites, and had almost twice the number of children and twice the rate of divorce. The authors concluded that these factors affect the ability of black and Hispanic students to pay off their loans.

Financial literacy. Being financially literate is vital in making correct financial decisions, thus, it is important for students to be financially literate, especially when financing their own education. Student uncertainty about how much to borrow for college might lead to poor financial outcomes.

Chen and Volpe (1998) surveyed 924 college students from different universities in order to gauge their financial literacy; they found correct responses accounted for only 53 percent of the questionnaire. Sometimes even parents are not financially literate enough to advise their children on financial issues. Perna (2008) collected data from a questionnaire made to 15 public high schools in five different states and found that parents from low-resource schools usually advised their children not to get student loans, whereas the opposite was true for middle- and higher-resource schools.

Christie and Munro (2003) reported that many students were unaware of the benefits and costs of obtaining a higher education. For example, in their study, 17 out of 49 students reported that although their parents saw attending college as something “normal” or “expected,” they never discussed the actual implications of such an act. It seemed that both the parents and the students simply assumed that the economic benefits of attending college always happened without even contemplating the actual expenses.

Making the loan decision. The conditions under which students ask for loans are not universal. Avery and Turner (2012) suggested that college students should consider many factors, such as expected degree completion, college major, and expected lifetime earning when evaluating the optimal amount to borrow for college. The college major is crucial in assessing how much to borrow, because different majors offer different returns on investment, and therefore offer different likelihoods of paying off student loans.

Carnevale, Cheah, and Hanson (2015) investigated the economic value of undergraduate college majors by looking at factors such as earnings and employment status. They reviewed 137 different majors, and results indicated that the highest-earning major was petroleum engineering with median earnings of $136,000, and the lowest-earning major was early-childhood education, with median earnings of $39,000.

Arcidiacono (2004) used data from the National Longitudinal Study of the High School Class of 1972 to study the different returns that different majors offered. By using regressions, maximum likelihood estimations, and simulations, Arcidiacono (2004) found larger monetary returns for majors requiring mathematical abilities.

Effect of parental savings. Elliott and Beverly (2011) used longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID)—specifically the PSID’s Transition into Adulthood Supplement and the Child Development Supplement—to determine that child development accounts (CDA) increase college attendance and graduation rates.

According to Elliott (2013), parental savings positively affect the child’s ability to graduate college—even if savings are small. Parental savings can be constrained based on the number of children. For instance, using data from the 1983 to 1986 Survey of Consumer Finances, Yilmazer (2008) found that the parental support for a child’s education decreased as the number of children increased. Similarly, Steelman and Powell (1991) suggested that the ability of parents to save for their children’s educational future depended first on their total income, and then on the number of children they had, since their total income would need to support their total number of children.

Based on the review of literature, there appears to be little emphasis on parents. Parental attitudes toward student loans have a direct effect on the level of student debt their children take on. Previous research has examined the influence of parental savings on children graduating college and the factors that affect parental savings for children’s college. However, few, if any, previous studies have examined how parents servicing their own student debt affects using education saving vehicles to save for their children’s college, as well as their decision to obtain student loans on behalf of their children. This research contributes to the literature by examining parental student debt and its affect on how parents view education financing.

Methodology

Data. This study used the 2012 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79). The cohort of NLSY79 initially contained a sample composed of 6,403 males and 6,283 females, totaling 12,686 respondents. The respondents were 14 to 22 years old at the time of the first survey. Currently, 9,964 respondents remain in that sample. In respect to race, the initial survey contained 7,510 respondents who were non-black/non-Hispanic, 3,174 black, and 2,002 Hispanic or Latino. Respondents were interviewed annually until 1994 and biennially thereafter. After adjusting for invalid responses, valid skips, people who answered “don’t know,” refused to answer, and were not interviewed, the number of observations decreased to 7,301 respondents.

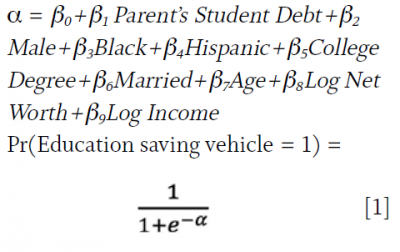

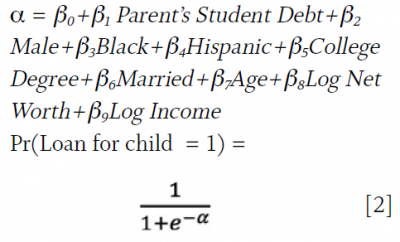

Empirical models. To determine the use of education saving vehicles, the following question was explored: Does an outstanding student loan balance of the parent affect utilizing saving vehicles such as Coverdell ESAs and 529 plans in order to save for their child(ren)’s education?

A binary logistic regression was used to obtain the likelihood of a parent using education saving vehicles to finance their child’s education based on their student loan balance.

To determine whether parental student loan debt affected their views on loans for their children, the following question was explored: Does an outstanding student loan balance of the parent affect taking out loans on behalf of the child(ren) for higher education?

A second binary logistic regression was used to assess the likelihood of a parent taking out loans on behalf of their child based on their own student loan balance.

Dependent variables. Education saving vehicles. Education saving vehicles is a dichotomous variable that assesses two outcomes: whether the parents are using education saving vehicles or not. If either the Coverdell or 529 plan were used, then it would indicate that a parent using education saving vehicles is true, otherwise, it is false.

Loan for child. This is a dichotomous variable that assesses two outcomes: whether the parent got student loans for their child(ren) or not. If the “loan balance for child” variable equals greater than zero, then the “loan for child” variable takes a value of 1; otherwise it gets the value of 0.

Hypothesis variable. Parent’s student debt is the hypothesis variable for this research. It is made dichotomous by making the numerical value equal to 1 when the parent’s student debt balance is greater than 0; otherwise, the numerical value is equal to 0.

Control variables. Sex. The sex of a parent may influence their views toward financing the education of their child. The human capital theory would predict that women are more likely to invest in their child’s education since they have, on average, longer life expectancies than men and would be able to gain more in the long run from the investment. To investigate if sex affects the dependent variables, the dummy variable “male” is included in the model (the reference variable is “female”).

Race. Past research has concluded that race is significant in determining degree completion, student loan defaults, and the probability of borrowing for school. Past research indicates that this variable is correlated to educational financial decisions. It is divided into two dummy variables, black and Hispanic, and one reference variable, non-Hispanic, non-white.

College degree. Based on the status attainment theory, there is a positive correlation between college attainment of the parent and the parent’s aspirations for their child to go to college, thus the parent is more likely to provide financial support for college. This variable is a dichotomous variable that assesses two outcomes, whether the recipient has a college degree or not. If the recipient has a bachelor’s degree or a higher degree, then the “college degree” variable takes numerical value 1; otherwise, it takes value 0.

Marital status. Marital status is included in the model because it affects the financial support a parent can grant his or her child. Based on the human capital theory, divorced parents may be more financially constrained than married parents. The models use the dichotomous variable “married.” If they answered “never married” or “other,” the variable takes on the numerical value 0; otherwise it takes the value 1.

Age. According to the life-cycle hypothesis, we have different propensities to consume in relation to saving depending on age. A younger person in the production stage may be able to afford the expense to fund an education savings account for his or her child(ren), as opposed to someone in the retirement stage.

Net worth. Based on the status attainment theory, net worth of a parent is positively correlated to the child’s educational achievement. The variable “net worth” is log transformed in order to reduce skewedness and for interpretation purposes. Furthermore, the net worth variable is from the year 2008 in order to assess how past net worth affected having a college savings account in the future.

Income. The status attainment theory also indicates a positive relationship between parent’s income and child’s educational attainment. The variable “income” is log transformed in order to reduce skewedness.

High financial literacy. People who are financially literate make smarter decisions with their money. They are more aware of financial products and understand the importance of financial planning. The “high financial literacy” variable is composed of three true or false questions. Respondents who answered the three questions correctly were labeled as having high financial literacy, otherwise they were not. Therefore, this variable is dichotomous. However, in the t-test, it is made continuous and is called “financial literacy index,” with values ranging from 0 to 3.

Descriptive Results

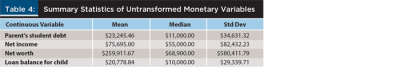

Table 4 shows the summary statistics. The mean, median, and standard deviation amount of parent’s student debt are $23,245.46, $11,000, and $34,631.31, respectively. The mean, median, and standard deviation of net income are $75,695, $55,000, and $82,432.23, respectively. The net worth’s mean, median, and standard deviation are $259,911.67, $68,900, and $580,411.79, respectively. Lastly, the mean, median, and standard deviation of amount owed on student loans for children are $20,778.84, $10,000, and $29,339.71, respectively.

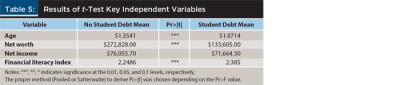

Table 5 shows the results from a t-test from those respondents who have student debt and from those that do not have student debt. The difference of the mean of age of the respondents who have student debt (51.07) is statistically different from the mean of age of those who do not have student debt (51.35).

The mean net worth of the respondents with student debt was $133,605, while the mean net worth of the respondents with no student debt was $272,828. Since it is statistically different, it means that in this sample the respondents that reported no student debt had 104.20 percent more net worth than those who reported having student debt. The difference of net income of these two groups is not statistically significant.

From a scale of 0 to 3, the mean financial literacy score for the respondents with student debt was 2.39 while the mean financial literacy score for the respondents with no student debt was 2.25; this difference proves to be statistically different, meaning that respondents reporting having student debt scored higher on the three financial literacy questions.

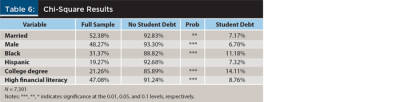

Table 6 shows the results of a chi-square test. It shows that 52.38 percent of the sample was married, and from these, 92.83 percent did not have student debt, and 7.17 percent had student debt. There is an association between being married and having student debt.

Males comprised 48.27 percent of the sample. Of that, 93.3 percent did not have student debt, and 6.7 percent had student debt. This research found an association between being a male and having student debt.

Blacks made up 31.37 percent of the sample; 88.82 percent of them did not have student debt and 11.18 percent did. This research found an association between blacks and having student debt. Hispanics made up 19.27 percent of this sample; 92.68 percent of them did not have student debt, and 7.32 percent did. Nevertheless, there is no association between Hispanics and student debt.

There were 21.26 percent of respondents with a college degree 85.89 percent of them did not have student debt, and 14.11 percent had student debt. This research found that there is an association between having a college degree and having student debt.

Lastly, 47.08 percent of respondents had high financial literacy; 91.24 percent of whom did not have student debt, and 8.76 percent of them did. There is an association between financial literacy and student debt.

Empirical Results

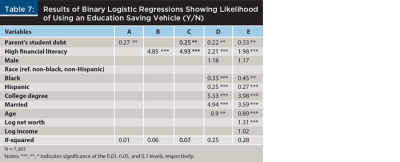

Table 7 provides the results of a binary logistic regression showing the likelihood of respondents using an education savings vehicle. It shows a step progression of how the model evolved with different control variables.

Column A of Table 7 only controlled for parent’s student debt, and this research found that parents who have student debt are 73 percent less likely to use an education savings vehicle.

Column B controlled solely for high financial literacy, and the research found that parents who have high financial literacy are 385 percent more likely to use an education savings vehicle. Column C controlled for parent’s student debt and high financial literacy. In this model, parents with student debt are 75 percent less likely to use an education savings vehicle, and parents with high financial literacy are 393 percent more likely to use an education saving vehicle.

It is important to note that all the control variables for the first three columns are statistically significant. The last column, E, which contains all the variables for the final model, shows that parents with student debt are 67 percent less likely to use educational saving vehicles for their children. Parents with high financial literacy were 98 percent more likely to use educational saving vehicles for their children. Gender was not statistically significant. Blacks were 55 percent less likely to use educational saving vehicles for their children compared to the reference group (non-black, non-Hispanic), and Hispanics were 73 percent less likely to use educational saving vehicles for their children compared to the reference group.

Parents with a college degree were 298 percent more likely to utilize educational saving vehicles than parents without a college degree. Respondents who are married were 259 percent more likely to utilize educational saving vehicles than those who are not married. Increasing age by one year represented an 11 percent decline in the odds of using educational saving vehicles for children. Increasing one unit of net worth meant a 31 percent increase in the odds of using educational saving vehicles for children. Net income was not statistically significant in this model. The R-squared of this final model is 0.2796.

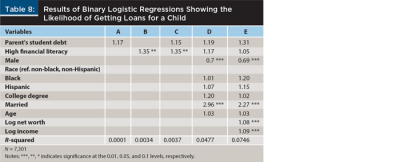

Table 8 provides the results of a binary logistic regression showing the likelihood of getting loans to finance a child’s college education, showing a step progression of how the model evolved with different control variables. In column A, the study controlled only for parent’s student debt, the variable was not statistically significant. In column B the study controlled exclusively for high financial literacy and observed that parents with high financial literacy were 35 percent more likely to get a loan to finance his or her child’s college. In column C, the study controlled for parent’s student debt and high financial literacy. The research found that parent’s student debt remained statistically insignificant and the results for high financial literacy remained the same.

The final model showed that parent’s student debt and high financial literacy were not statistically significant. Race, age, and college degree were also not statistically significant in the model. Males were 31 percent less likely to get a loan for a child, compared to females. Parents who are married were 127 percent more likely to get a loan for a child compared to parents that are not married. A unit increase in net worth resulted in an 8 percent increase in the odds of getting a loan for children. Increasing income by a unit resulted in a 9 percent increase in odds of getting a loan for children. The R-squared of this model is 0.0746.

Conclusion

Parental views of education financing play a significant role in children being able to obtain a college degree. It is important to understand the factors that affect parental views of education financing, because it could help in creating policies aimed for an increase in college attendance by targeting the parents. This research contributes to the literature by focusing on how parental student debt affects parental views of education financing.

The main findings showed that parents who are currently servicing their own student loans are 67 percent less likely to use a tax-advantaged education savings vehicle such as a Coverdell ESA or a 529 plan, versus parents with no student debt. Implications suggest that parents who still service their own student loan debt are prolonging the cycle of debt burden of their children by not saving for their education. Parental student loan debt does not appear to affect the decision of parents obtaining student loans for their children nor the loan amount for their children.

Ignoring parental emotions, it is not rational for parents to save for their child’s college education in favor of securing adequate retirement savings for themselves. The life-cycle hypothesis describes three distinct stages: the preproduction stage, production stage, and retirement stage. People in the preproduction stage are typically younger individuals, and the people of the production stage are typically middle-aged. This hypothesis states that usually, the propensity to consume in relation to saving is greater for the preproduction stage and retirement stage. The reason is that retired people are using their savings and usually not earning income anymore, and people in the preproduction stage usually have higher expenses than their incomes, due to still being in college or barely joining the labor force. Production stage individuals have a higher propensity to save due to usually earning more income in relation to their expenses.

Therefore, a parent in the production stage has an optimal strategy to save for retirement instead of saving for the college education of their child because the parent is approaching their retirement stage, thus they need to have an adequate amount in the retirement account sooner.

Moreover, the child will more likely be able to pay off his or her own student loans when he or she reaches the production stage. The child also has the ability to borrow for college, but the parent does not have the ability to borrow for retirement. Future research should examine how parental retirement accounts affect parental views toward education financing. It would be interesting to examine whether or not racial differences affect the decision to save for retirement and/or save for education.

Implications for Financial Planners

To reduce the prolonged cycle of student loan debt among parents and children, financial planners have an opportunity to educate their clients on the benefits of saving in dedicated education savings accounts, like a Coverdell ESA or 529 plan. Financial planners should increase awareness of the tax advantages of the various savings vehicles used for education.

Also, there are many alternatives to borrowing and saving for post-secondary education. First, financial planners should encourage their clients to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) each year. In 2018, around $2.6 billion of federal Pell grant money was unclaimed by eligible high school graduates because they failed to complete the FAFSA.2 Financial planners can help provide clients with the knowledge to help navigate the world of financial aid. Another alternative is to apply for outside scholarships.

A 2019 Journal of Financial Planning article3 suggested there are billions of scholarship dollars awarded each year, but much of that money is unclaimed. Parents should also encourage their children to take classes in high school that qualify for college credit. These high school classes are typically less expensive or even free to take.

Financial planners should also educate their clients on managing the expectations of their children. A February 2019 Journal of Financial Planning article4 stressed the importance of discussing college education and funding with children. Setting expectations about the amount of funding parents are willing to offer and the amount of loans that are reasonable are important factors parents should consider.

Last, there are some techniques financial planners can use to minimize the impact of saving for college. Planners can help clients save for their children’s college education by suggesting various ways to budget for the future expenses. One suggestion is that parents redirect the money they used toward full-time daycare toward saving for college in a dedicated college savings account like a 529 plan. Another suggestion is finding an alternative to daycare and allocating those funds to a dedicated savings account or saving a portion of one spouse’s income specifically for children’s education.5

Financial planners need to be aware of the impact that parental views of student loan debt can have on children’s education decisions. Not only do the parents’ views influence the decision to obtain funding, but they may also influence the decision to even attend. In addition, financial planners can focus on the factors that influence parent’s views and seek to implement policies that can target those factors.

According to this study, parents who are paying off their own student debt are less likely to invest in tax-advantaged accounts for their children’s education. Financial planners can introduce the concept of these accounts early to these clients to educate them on the potential losses they face by not using these accounts. While these parents may prefer to pay off their own debts in an effort to secure their retirement, planners can show the benefits of working on these goals in tandem.

Additionally, financial planners can educate parents on the other options available for students to fund their college education. It should not be solely up to the parents to fully fund their child’s education, especially if they are still financing their own debt. Again, by targeting the parents who are still under this financial burden, financial planners can provide options ahead of time. These options can be worked into the comprehensive financial plan so that parents do not feel overwhelmed with paying down their own debt while saving for their children at the same time. Not only can students obtain scholarships, but they may also qualify for other aid by using the FAFSA. Financial planners can encourage parents who are paying off student debt to get the FAFSA in early to avoid their children being in the same situation.

Endnotes

- Earnings and unemployment rates by educational attainment available at www.bls.gov/emp/chart-unemployment-earnings-education.htm.

- See “Students Missed Out on $2.6 Billion in Free College Money,” by Anna Helhoski. Posted Oct. 16, 2018 by NerdWallet. Available at nerdwallet.com/blog/2018-fafsa-study.

- See the February 2019 Journal of Financial Planning Observer article, “Discussing College Funding with Children.”

- See the February 2019 Journal of Financial Planning Observer article “Alternatives to Borrowing for College.”

- See “College Savings Tips for Working Parents,” by Kathryn Flynn. Posted March 1, 2019 by SavingForCollege.com. Available at savingforcollege.com/article/college-savings-tips-for-working-parents.

References

Arcidiacono, Peter. 2004. “Ability Sorting and the Returns to College Major.” Journal of Econometrics 121 (1): 343–375.

Avery, Christopher, and Sarah Turner. 2012. “Student Loans: Do College Students Borrow Too Much—Or Not Enough?” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 26 (1): 165–192.

Baker, Amanda R., Benjamin D. Andrews, and Anne McDaniel. 2017. “The Impact of Student Loans on College Access, Completion, and Returns.” Sociology Compass 11 (6): e12480.

Baum, Sandy, and Marie O’Malley. 2003. “College on Credit: How Borrowers Perceive Their Education Debt.” Journal of Student Financial Aid 33a (3a): 7–19.

Belfield, Chris, Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, and Laura Van Der Erve. 2017. “Higher Education Funding in England: Past, Present and Options for the Future.” Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing Note BN211. Available at ifs.org.uk/publications/9334.

Bennett, Doris, Cynthia McCarty, and Shawn Carter. 2015. “The Impact of Financial Stress on Academic Performance in College Economics Courses.” Academy of Educational Leadership Journal 19 (3): 25–30.

Bozick, Robert. 2007. “Making It Through the First Year of College: The Role of Students’ Economic Resources, Employment, and Living Arrangements.” Sociology of Education 80 (3): 261–285.

Callender, Claire, and Jonathan Jackson. 2005. “Does the Fear of Debt Deter Students from Higher Education?” Journal of Social Policy 34 (4): 509–540.

Cappelli, Peter, and Shinjae Won. 2016. “How You Pay Affects How You Do: Financial Aid Type and Student Performance in College.” National Bureau of Economic Research paper No. w22604.

Carnevale, Anthony P., and Jeff Strohl. 2013. “How Increasing College Access Is Increasing Inequality, and What to Do About It.” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Available at cew.georgetown.edu/how-increasing-college-access-is-increasing-inequality-and-what-to-do-about-it-2.

Carnevale, Anthony P., Ban Cheah, and Andrew R. Hanson. 2015. “The Economic Value of College Majors.” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Available at repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1050288.

Chen, Haiyang, and Ronald P. Volpe. 1998. “An Analysis of Personal Financial Literacy Among College Students.” Financial Services Review 7 (2): 107–128.

Christie, Hazel, and Moira Munro. 2003. “The Logic of Loans: Students’ Perceptions of the Costs and Benefits of the Student Loan.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (5): 621–636.

Cunningham, Alisa F., and Deborah A. Santiago. 2008. “Student Aversion to Borrowing: Who Borrows and Who Doesn’t.” A report by the Institute for Higher Education Policy. Available at ihep.org/research/publications/student-aversion-borrowing-who-borrows-and-who-doesn’t.

Davies, Emma, and Stephen E.G. Lea. 1995. “Student Attitudes to Student Debt.” Journal of Economic Psychology 16 (4): 663–679.

Dynarski, Mark. 1994. “Who Defaults on Student Loans? Findings from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study.” Economics of Education Review 13 (1): 55–68.

Dynarski, Susan M., and Judith E. Scott-Clayton. 2006. “The Cost of Complexity in Federal Student Aid: Lessons from Optimal Tax Theory and Behavioral Economics.” National Bureau of Economic Research paper No. w12227.

Dynarski, Susan M., and Judith E. Scott-Clayton. 2013. “Financial Aid Policy: Lessons from Research.” National Bureau of Economic Research paper No. w18710.

Elliott III, William. 2009. “Children’s College Aspirations and Expectations: The Potential Role of Children’s Development Accounts (CDAs).” Children and Youth Services Review 31 (2): 274–283.

Elliott, William, and Sondra Beverly. 2011. “Staying on Course: The Effects of Savings and Assets on the College Progress of Young Adults.” American Journal of Education 117b (3): 343–374.

Elliott, William, and Ilsung Nam. 2013. “Is Student Debt Jeopardizing the Short-term Financial Health of U.S. Households?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 95 (5): 405–424.

Elliott, William. 2013. “Small-Dollar Children’s Savings Accounts and Children’s College Outcomes.” Children and Youth Services Review 35 (3): 572–585.

Flint, Thomas A. 1997. “Predicting Student Loan Defaults.” Journal of Higher Education 68 (3): 322–354.

Gervais, Martin, and Nicolas L. Ziebarth. 2019. “Life After Debt: Postgraduation Consequences of Federal Student Loans.” Economic Inquiry 57 (3): 1,342–1,366.

Gladieux, Lawrence, and Laura Perna. 2005. “Borrowers Who Drop Out: A Neglected Aspect of the College Student Loan Trend.” National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education Report No. 05-2. Available at files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED508094.pdf.

Horn, Laura J., Xianglei Chen, and Chris Chapman. 2003. “Getting Ready to Pay for College: What Students and Their Parents Know about the Cost of College Tuition and What They Are Doing to Find Out.” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics Report No. 2003-030. Available at eric.ed.gov/?id=ED480471.

Jackson, Brandon A., and John R. Reynolds. 2013. “The Price of Opportunity: Race, Student Loan Debt, and College Achievement.” Sociological Inquiry 83 (3): 335–368.

Johnson, Elizabeth, and Margaret S. Sherraden. 2007. “From Financial Literacy to Financial Capability Among Youth.” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 34 (3): 119–145.

Kim, Dongbin. 2004. “The Effect of Financial Aid on Students’ College Choice: Differences by Racial Groups.” Research in Higher Education 45 (1): 43–70.

Kim, Dongbin. 2007. “The Effect of Loans on Students’ Degree Attainment: Differences by Student and Institutional Characteristics.” Harvard Educational Review 77 (1): 64–100.

Knapp, Laura Greene, and Terry G. Seaks. 1992. “An Analysis of the Probability of Default on Federally Guaranteed Student Loans.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 74 (3): 404–411.

Light, Audrey, and Wayne Strayer. 2000. “Determinants of College Completion: School Quality or Student Ability?” Journal of Human Resources 35 (2): 299–332.

Long, Bridget Terry, and Erin Riley. 2007. “Financial Aid: A Broken Bridge to College Access?” Harvard Educational Review 77 (1): 39–63.

McDonough, Patricia M., and Shannon Calderone. 2006. “The Meaning of Money: Perceptual Differences Between College Counselors and Low-Income Families about College Costs and Financial Aid.” American Behavioral Scientist 49 (12): 1,703–1,718.

Nam, Yunju, Youngmi Kim, Margaret Clancy, Robert Zager, and Michael Sherraden. 2013. “Do Child Development Accounts Promote Account Holding, Saving, and Asset Accumulation for Children’s Future? Evidence from a Statewide Randomized Experiment.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32 (1): 6–33.

Paulsen, Michael B., and Edward P. St. John. 2002. “Social Class and College Costs: Examining the Financial Nexus Between College Choice and Persistence.” The Journal of Higher Education 73 (2): 189–236.

Perna, Laura W. 2008. “Understanding High School Students’ Willingness to Borrow to Pay College Prices.” Research in Higher Education 49 (7): 589–606.

Rothstein, Jesse, and Cecilia Elena Rouse. 2011. “Constrained After College: Student Loans and Early-Career Occupational Choices.” Journal of Public Economics 95 (1): 149–163.

Souleles, Nicholas S. 2000. “College Tuition and Household Savings and Consumption.” Journal of Public Economics 77 (2): 185–207.

Steelman, Lala Carr, and Brian Powell. 1991. “Sponsoring the Next Generation: Parental Willingness to Pay for Higher Education.” American Journal of Sociology 77 (2): 1,505–1,529.

Volkwein, J. Fredericks, Bruce P. Szelest, Alberto F. Cabrera, and Michelle R. Napierski-Prancl. 1998. “Factors Associated with Student Loan Default Among Different Racial and Ethnic Groups.” The Journal of Higher Education 69 (2): 206–237.

Walpole, MaryBeth. 2003. “Socioeconomic Status and College: How SES Affects College Experiences and Outcomes.” The Review of Higher Education 27 (1): 45–73.

Yilmazer, Tansel. 2008. “Saving for Children’s College Education: An Empirical Analysis of the Trade-off Between the Quality and Quantity of Children.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 29 (2): 30–324.

Zhan, Min, and Michael Sherraden. 2011. “Assets and Liabilities, Educational Expectations, and Children’s College Degree Attainment.” Children and Youth Services Review 33 (6): 846–854.

Citation

Martin, Terrance, Lua Augustin, Laura Ricaldi, and Jose Nunez. 2020. “The Effect of Student Loans on Parental Views of Education Financing.” Journal of Financial Planning 33 (5): 46–55.