Journal of Financial Planning: April 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Donovan Sanchez, CFP®, is a personal financial planning instructor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, a senior financial planner with Model Wealth, Inc., and a Ph.D. student at Kansas State University.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT-I, is an assistant professor in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. McCoy volunteers for the Financial Therapy Association Board of Directors and serves as the co-editor of the Financial Planning Review.

Khurram Naveed, a CFA charterholder and CFP® professional, holds a Bachelor of Science in Economics, a Master of Arts in Economics, and an M.B.A. from the University of Missouri-St. Louis. He is currently a Ph.D. student at Kansas State University.

Blake Gray, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. Gray is part of the Powercat Financial Education initiative and serves as a board member for Habitat for Humanity of the Northern Flint Hills.

Executive Summary

- A strong practitioner–academic partnership is essential to financial planning’s evolution as a profession. Without this partnership, academics risk producing research that does not inform financial planning practice, and practice risks not being evidenced-based.

- The reasons for this gap can be explained by the two communities theory (Caplan 1979). Advisers and academics inhabit two different communities with differing jargon, incentives, and metrics for success.

- Improving communication between these communities (such as the adviser survey presented here) can help increase the likelihood of a virtuous cycle in which advisers inform academic questions and academic answers inform adviser practice.

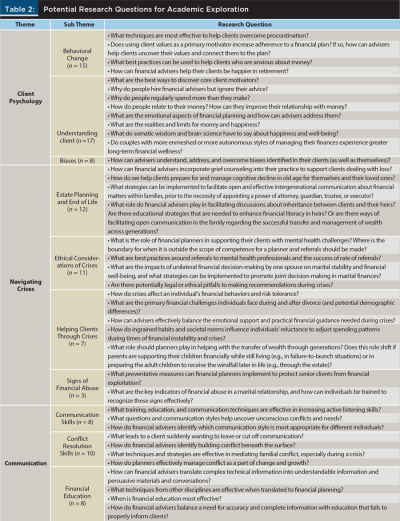

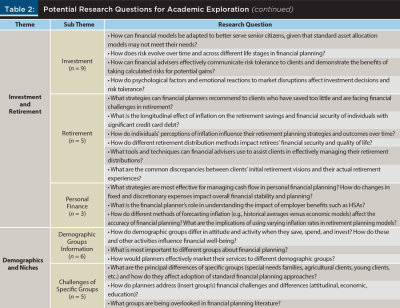

- Participants completed a survey asking which topics would benefit from more research. Responses were categorized into six themes, including: (1) client psychology (n = 40); (2) crises (n = 33); (3) communication (n = 26); (4) investment and retirement (n = 17); (5) demographics/niches (n = 11); and (6) other (n = 36).

- Practitioner call to action—Reach out to an academic and invite them to lunch or to meet at your office. Tell them about the concerns you have in your practice, the questions you are wondering about, and the struggles you have serving your clients.

- Academic call to action—Reach out to a practitioner and invite them to lunch or to meet you on campus. Invite them to share their knowledge with you and your students (e.g., guest lectures, panel discussions), and seek to understand the important questions they are wondering about. Explore these questions and design research that applies to practitioners.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

In 2011, Buie and Yeske argued that more evidence-based practice is needed as financial planning moves toward wider acceptance as a profession. They also note that in the established professions (like medicine and law), an “essential partnership” exists between practitioners and academics. The reason for this partnership is simple: Practitioners know the questions that need answering, and academics have the tools to address them through formal research processes (Buie and Yeske 2011). To realize the vision of a stronger practitioner-academic partnership, two important customs should become commonplace: (1) academics should produce research that practitioners deem relevant; and (2) practitioners should consume financial planning research. Our paper calls on advisers and academics to bridge the gap—to make connections so that practice informs research, and research drives relevant knowledge.

This is not the first time such an endeavor has taken place. In 2020, Bogan et al. (2020) provided a forward-looking research agenda for financial planning academics. More specifically, Bogan et al. conducted a survey of researchers (60 percent) and practitioners/affiliates (40 percent) with the goal of identifying topics to guide the next decade of financial planning research. The present study builds on this important work by expanding the sample size and focusing the survey primarily on practitioners. This study seeks to answer the question, “what topics do practitioners believe would benefit from more research to help them improve their work with clients?” We hope that current and future financial planning academics will use the answers to this question to inspire research projects. We also hope that practitioners will support research initiatives through meaningful dialogue, collaboration, and financial support.

Literature Review

Why do gaps exist between practitioners and academics? Caplan (1979) posited that researchers and practitioners occupy two distinct communities with differing values, reward systems, and languages, thereby creating alignment challenges. Though Caplan’s work focused on federal executives, the theory has important parallels applicable to financial planning. Financial planning academics and practitioners tend to occupy separate communities in which values and rewards are quite distinct from their counterparts.

For example, practitioners are interested in serving clients more efficiently, improving client outcomes, and increasing profitability. Academics, on the other hand, want to make an impact on policy and best practices, see their work published in reputable journals, and be cited widely by their peers. While practitioners are eager to grow and improve client service, academics pursue tenure with similar energy and focus. Of course, the gap between researchers and practitioners is not for a lack of hardworking, driven, and enthusiastic individuals in both communities. Instead, this gap is a result of two groups focusing on quite different targets, with different metrics for success. To be sure, there are also situations in which biases or pride get in the way of academics and practitioners establishing authentic connections.

While community differences can result in synergistic exchange of specialized advantages (Mizrahi et al. 2008), gaps between communities can also result in suboptimal communication that prevents exchange. Examples include academics doing research that is not read, and practitioners failing to implement research-based best practices. Missed opportunities to advance the profession will almost certainly occur if practitioners and academics fail to work in partnership.

Fothergill (2000) suggests practical ways to bridge the gap between practitioners and researchers, including organizing meetings to better understand one another’s goals, jointly designing research that has practical applications, and setting up groups to support these efforts. Bridging gaps begins with increasing dialogue between communities to see the ways targets may be better aligned. This project is one step in the direction of improved alignment.

Method

Participants

This study was conducted in collaboration with the Financial Planning Association (FPA). Following the receipt of Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from Kansas State University, an electronic survey was disseminated to FPA membership via direct email. The survey link was also shared on social media by both the Kansas State University research team and FPA members. To enhance the survey’s reach, select individuals received a personalized email from the research team, encouraging participation.

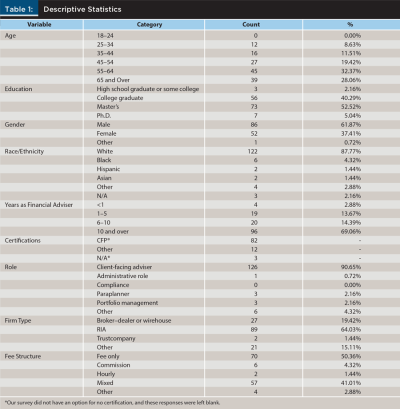

The survey garnered 293 responses. Subsequent data cleaning procedures resulted in a final sample size of n = 139. The characteristics of the sample are detailed in Table 1. (Please note that participants may hold multiple certifications simultaneously, so we include just the count for these demographics.)

Analysis

Respondents were asked to provide open-ended responses to the following question: “As a means of helping improve your work with clients, what topics do you believe would benefit from more research?” Some respondents provided answers with multiple components. In those cases, answers were divided into unique responses to categorize. Though this creates some respondents being counted under multiple themes, this enabled us to better capture the different themes expressed by participants.

Themes were initially extracted using a qualitative approach called thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun 2017). Two of the authors were tasked with creating the codebook, but the responses proved difficult to categorize. Instead, the entire research team met weekly for approximately three months to discuss interpretations of responses that were lacking consensus. Responses were ultimately categorized across six themes, as follows: (1) client psychology (n = 40); (2) crises (n = 33); (3) communication (n = 26); (4) investment and retirement (n = 17); (5) demographics/niches (n = 11); and (6) other (n = 36).

Results and Discussion

Before providing a detailed description of the themes that emerged in this study, it will be helpful to revisit the Bogan et al. (2020) study’s findings to explore how practitioner interest has shifted in the past four years. The Bogan et al. (2020) survey indicated a need for more research in (1) technology; (2) client behavior/psychology; (3) retirement, decumulation, and demographics; (4) impact investing, ESG, and social responsibility; and (5) ethics. Our survey suggests that research interests have shifted in meaningful ways. For example, respondents to our survey did not emphasize a need for research in impact investing; environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG); and social responsibility. Nor was technology a focus—a somewhat paradoxical finding considering the attention that artificial intelligence has garnered recently—but possibly explained by survey construction. Instead, respondents emphasized research that helps practitioners better understand and help clients navigate the complexities and challenges of the human experience.

A notable similarity between Bogan et al. (2020) and this study’s results are that respondents highlight an interest in client psychology research. This is not entirely surprising. With the rise of automation produced by planning technology (e.g., Chaffin 2018; CFP Board 2022), the role of the planner has transformed from transactional to relational. Dubofsky and Sussman (2009) interviewed planners about the changing role of financial planners and found that “approximately 25 percent of the respondents’ contact with clients is devoted to non-financial issues” (48). In line with this finding, respondents expressed a need for research to help them navigate crisis events, including end of life challenges, divorce, and mental health issues. Though we live in an era when technology appears to be on the brink of changing the human experience (once again), financial advisers want research that helps them strengthen relationships and improve their ability to address the mental/emotional experience of their clients.

The disparate findings between surveys highlight the need for regularly resurveying practitioners (perhaps every few years) to understand the changing questions and challenges they face and lead to the results of our present study. The subsequent sections will describe key quotes from survey participants, contextualize themes within the existing literature, and propose research questions for academics to explore.

Client Psychology

Client psychology garnered the most participant responses. As the profession evolves, there is a growing awareness for a need to better understand human psychology. In fact, as a result of the CFP Board’s 2021 Practice Analysis Study, a new principal knowledge domain was created called “Psychology of Financial Planning,” and was required to be included in instruction in CFP Board-registered programs effective 2022 (CFP Board 2021). Financial planning academics have been interested in this theme for some time. For example, Asebedo and Seay (2015) showed how positive psychology could be used to help clients maximize well-being during transitional periods. Similarly, Lawson and Klontz (2017) showed how behavioral finance, financial psychology, and financial therapy could be used in conjunction with the CFP Board’s financial planning process to address emotional and behavioral aspects of a client’s relationship with money. And two textbooks, Client Psychology (Chaffin 2018) and The Psychology of Financial Planning (Chatterjee et al. 2023), serve as an impressive introduction to research around human psychology as it relates to financial planning. Within this theme, three major subthemes were identified, including: (1) behavior change; (2) understanding clients; and (3) biases. These subthemes are discussed below.

Behavioral change. Financial planners are in the business of delivering advice, so it is natural that they are interested in research that helps them influence behavior change. Responses in this area ranged from simply “behavior modification” to “using client’s values as the primary motivator to increase adherence to their financial plan.” In general, responses suggest a desire to help clients on issues ranging from overcoming procrastination, better connecting core values to desirable behaviors, and helping clients stick with their plan. Theories related to behavior and behavior change have begun being used in financial planning research, such as the transtheoretical model of health behavior change (Prochaska and DiClemente 1983; Prochaska and Velicer 1997), and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991). In fact, in a review of research between 1990 and 2022 in the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, Goyal and Kumar (2023) found that out of 523 studies, the theory of planned behavior and the transtheoretical model of behavior change were leading theories, appearing in 10 articles each. To provide context, the top three theories include the life cycle hypothesis (23 articles), expected utility theory (20 articles) and human capital theory (11 articles). To help address behavior change, Britt et al. (2016) measured the influence that physiological stress had on client readiness to change and provided strategies for how planners can decrease stress.

Understanding clients. The second subtheme showed that respondents also want research that helps them better understand their clients. For example, participants expressed a need for more research exploring the human relationship to money, why people tend to spend more than they earn, holistic and wellness matters, and behavioral finance. While the former subtheme deals with understanding how to influence human behavior, this subtheme expresses a desire to understand why people do what they do. This improved understanding could help practitioners guide their clients to healthier and happier decisions. As noted by McCoy et al. (2022), understanding client values is key to building trust and commitment.

Biases. Though not as pronounced as the two prior subthemes, respondents also want research on biases. Responses include, “behavioral financial issues,” “understanding emotional bias,” “addressing confirmation bias,” and “overcoming biases.” Research in this area could help advisers identify blind spots in their clients (as well as themselves), and work in ways that can proactively address this human tendency. Biases are the cornerstone to behavioral finance. While behavioral finance appears to fall into the larger context of client psychology for this paper, the research team recognizes that behavioral finance really is a category unto itself. Although comparatively few respondents highlighted biases as an area needing additional research, the research team expects it will persist as a topic of interest among financial planners in the future.

Navigating Crises

Results from our survey suggest that research is needed to understand what interventions, skills, and techniques can aid planners in supporting their clients through crisis events. This parallels the earlier work of Dubofsky and Sussman (2009) who surveyed advisers and surmised that “planners help clients with critical issues that reflect human drama and frailties: religion and spirituality, death, family dysfunction, illness, divorce, and depression” (48). Individuals often turn to financial advisers in response to significant life, stressor, or crisis events (Opiela 2001). Four major subthemes emerged, including: (1) how to help clients through times of crisis; (2) estate planning and how to prepare clients for end of life; (3) ethical considerations around crises events; and (4) signs of financial abuse, financial manipulation, or financial exploitation.

Helping clients through crises. With respect to the first subtheme, topics include economic crises (e.g., losing a job, windfalls), personal crises (e.g., mental incapacity, mortality, mental illness), and relational crises (e.g., divorce, financial exploitation, conflict). Respondents also highlighted crisis events that are not inherently negative but may have emotional or behavioral consequences, such as windfalls and inheritances. This choice of including both negative and positive crises was derived from research in family science that has found that even joyous events (such as marriage or the arrival of a new baby) can be experienced as a crisis event for families (McCubbin, Hamilton, and Patterson 2014). Regardless of whether the crisis is a happy occasion or more challenging—such as a severe medical diagnosis, divorce, or the loss of a loved one (Gallo 2006)—many crisis events involve both financial and emotional components that fall to the planner to deal with or (at least) triage (Byram et al. 2024).

Estate planning and end of life. The crisis event most cited as needing more research was the end-of-life experience. Participants want to understand how to navigate the emotional dimensions around this subtheme. Examples include, “how to normalize talking about money within families (between generations) before a POA, guardian, trustee, or executor is needed,” and “prepare for mental incapacity and appoint trusted contact.” Talking about money does not come easily for many families. McCoy et al. (2019) found that 83 percent of respondents had not talked to a single other person in an entire year about money. Combining death and the transfer of money can make the conversation incredibly difficult. Recent surveys found most people (68 percent) understand it is important to talk to their loved ones about their end-of-life plans, but less than half brought it up to a family member (Ethos 2022). These are not easy conversations, so practitioners want research on best practices surrounding the planner’s role in preparing clients for mental incapacity, death, and dying. Advisers want to understand not only how to manage estate planning logistics (like determining trustees and executors), but also how to manage the emotional aspect of the end of life.

Ethical considerations of crises. Respondents were also curious about the planner’s role in crisis events (e.g., “grief counseling as a financial adviser,” “helping clients with mental health issues,” “understanding how to navigate difficult emotional situations for clients”). Practitioners want research to help them empathetically support their clients but are not sure what their role should be in crisis situations. Respondents also wondered when they should make referrals to outside professionals with responses like, “I have always had a hard time understanding the line between financial counseling and therapy. As a financial planner, I’d love to better understand when I am qualified to serve clients from an emotional capacity and when I should refer them to a therapist instead.” This blurred line between when to provide advice and when to make a referral to other helping professionals makes sense if one considers how interwoven financial matters are to overall well-being and mental health functioning. For example, being in debt has been found to worsen anxiety symptoms, and individuals who are trying to get out of debt are less likely to succeed if they have a mental health diagnosis (Bond and D’Arcy 2021; Evans et al. 2019). So future research would benefit from defining the scope of competence of financial planners in crisis situations, examining the success rate of referring to mental health professionals, looking at how to find and vet mental health professionals, as well as the potential legal/ethical pitfalls of making recommendations to mental health professionals.

Signs of financial abuse, manipulation, or exploitation. Finally, a handful of respondents asked for research on financial abuse, financial manipulation, or financial exploitation. Responses include, “learning to spot financial abuse in marital relationship” and “senior financial exploitation is woefully under researched.” Studies have found that financial abuse is present in 76 to 99 percent (Johnson et al. 2022) of domestic violence cases and often occurs early in relationships to reduce the partner’s ability to leave when the abuse occurs. In our study, respondents asked for research that specifically looks at financial exploitation to aid planners in recognizing financial abuse and then knowing resources that can support the client in the aftermath. Furthermore, the Senior Safe Act made certain firms and financial institutions required to complete trainings on elder financial abuse and exploitation in several states and territories (specifically Connecticut, Florida, Nevada, New Mexico, Washington, and Puerto Rico; FINRA n.d.). However, the act has not been passed in most states, leaving financial planners unsure of their role in financial abuse in elder clients. Research is needed to examine what that role is and how to help.

Communication

Survey respondents cite communication as an area needing additional research. Three subthemes emerged: (1) communication skills; (2) conflict resolution; and (3) financial education. In general, participants expressed a need for research to help them better listen to clients, navigate conflicts and tense issues, and share information in a way that can be easily understood. These themes are interwoven together as challenges between planners and clients, and often occur when clients feel they are not being heard, the planners are misaligned with client goals, or external conflicts are brought into the meeting to be resolved (Asebedo and Purdon 2018).

Communication skills. Respondents want to learn “how to actively listen, find the need behind the need, and accomplish the actual meeting agenda all within an hour.” To understand clients, participants want research on “counseling skills, specifically the right questions to ask to dig deeper into the emotional component of behaviors and then know what to do with that information.” Effective communication between planners and clients results in helping relationships where shared goals are achieved through intentional activity to overcome conflict and obstacles (Brammer and MacDonald 2002). While technical knowledge is important, it may not translate into shared action unless paired with strong communication that helps the planner motivate application (Asebedo 2019).

Conflict resolution skills. Respondents also want research on how to manage and resolve conflicts. Research that helps planners negotiate with clients who “suddenly want to move assets” or “shut down immediately when in meetings and/or only want to communicate through email or text.” Participants also want research on mediating conflicts from sibling rivalries, beneficiaries after a client’s death, between spouses, and during divorces. Some of these are closely related to the crisis events discussed in the prior theme. Frameworks for conflict resolution tactics are common in the practice of financial planning. There are also several articles that translate frameworks from other professions into financial planning, provide clear structure for both understanding and application, and give examples of how to integrate these frameworks into practice standards. Asebedo (2016) and Asebedo and Purdon (2018) are a few examples of adapting a framework from another domain into financial planning. However, these frameworks often lack empirical testing that would grant credence to their efficacy or help flesh out ways to adapt them for success in different situations.

Financial education. Finally, respondents want research on how to “simplify complex financial topics” to better educate clients, families, and children “without abandoning true precision and expertise.” Planners want to maintain the accuracy of their advice yet deliver it in ways clients can easily understand and apply. Naturally, the answer may lie within the educational research domain. Financial planning researchers have found benefits in replicating concepts, study designs, and variables from counseling and family science literature to better attend to the client’s underlying values, beliefs, and change motivators (e.g., Archuleta and Lutter 2020; Grable et al. 2015; McCoy et al. 2024). An example in financial planning literature would be from Sterbenz et al. (2021), which adapted a teaching method from scaffolding learning theory to financial planning and literacy efforts. Empirical testing of adapted education theories would validate or reject theoretical elements and provide practitioners and academics with evidence-based practice areas for further research.

Investment and Retirement

Survey responses highlighted the enduring need for research on investing and retirement planning. These two areas have been core to the traditional role of financial planners. Responses to this survey, however, focused on advancing research to include psychological and emotional factors and traditional investment and retirement concerns.

Investments. Respondents expressed interest in research that delves into the psychological dimensions of investment decisions and risk tolerance (e.g., “emotional reaction to market disruption”). Respondents expressed a desire to better understand risk, such as “What truly is risk ... How it evolves/adjusts/changes over time and within time-periods.” These responses underscore the need for research that can help clients maintain a balanced perspective on risk and return. Financial advisers continue to seek insights into how risk tolerance, cognitive biases, and emotional decision-making influence client behavior in dynamic market conditions. While strong research on these topics exists, more research is needed that translates findings into actionable strategies that advisers can implement to enhance client outcomes.

Retirement. Regarding retirement planning, one participant points out the lack of evidence-based tools to assist with these challenges: “I see clients having different visions of retirement often. I have several tools to flush this out and get clients to find clarity, but I rarely see [evidence-]based tools to help with this.” Moreover, respondents indicated a desire for greater understanding of retirement best practices and assumptions (e.g., “Client has saved too little—living too long and is now facing a challenging retirement,” and “Reasonable assumptions for inflation”). Prior research has explored behavioral finance, investment decision-making under uncertainty, and the impact of psychological factors on retirement planning (Mitchell and Utkus 2006; Mulvey and Shetty 2004; Wang and Shi 2014).

Technical retirement planning research continues to be a significant focus of the profession. For example, “retirement” was the second most common word used in Journal of Financial Planning abstracts, with only the word “financial” occurring more frequently (Anderson et al. 2022). Researchers have written extensively on the topic of retirement distribution (Bengen 1994; Guyton and Klinger 2006; Finke et al. 2013). The request for more research in this area may highlight a need to reinvestigate prior retirement research in light of present-day economic circumstances. For example, distribution strategies under a low-yield market environment may not be as applicable today, given the relatively higher yields. Additionally, these requests could highlight the gap between practitioners and researchers, as practitioners may not be aware of the current research available to them. To help bridge this gap, researchers should not only continue investigating the technical aspects of retirement planning but also do so in a way that emphasizes real-world applications.

Demographics/Niches

Participants expressed a desire to better understand demographic client groups. Perhaps, this is due to financial planners’ increased satisfaction when working with a specific niche (Lurtz 2023). Groups ranged from the young to the old and even include the in-between (sandwich generation struggles). There were two subthemes, including a call for more general research on broad demographic groups, and research focused on challenges that more specific groups face. In general, participants sought information to better understand, market to, and focus best practices targeting different cohorts.

General research on demographic groups. General comments about “wealth accumulation (or lack thereof) by generation” and “demographic patterns for spending, savings, retirement, and financial well-being” highlight a desire by participants to better understand broad demographic financial behavior. Luther et al. (2018) examined how different generations view financial planners and provided guidance on how firms might tailor marketing and communication to appeal to target groups more effectively. Expanding research to include more groups and different aspects of financial planning and then testing recommended strategies for effectiveness would address the current gap in research and practice.

Challenges of specific groups. On the other hand, some specific groups were identified as needing more research to understand how to better serve them, including special needs planning, agricultural clients, sandwich generation clients, younger clients, clients with aging parents, widows, and neurodivergent individuals. Some of these groups have a significant volume of research about them, while others are more rarely discussed (Goyal and Kumar 2023). While the volume may match the complexity and demand for research on some niches, it most likely does not. This leaves room for academics to expand or deepen research. However, the gap between existing research and statement of need for research raises questions about the degree to which practitioners are aware of, or accessing, current research.

Other

This theme includes difficult to categorize or decipher responses (e.g., “Everything,” “More clarity”), responses indicating that no additional research is needed (e.g., “none,” “Nothing in particular”), or that simply state “not applicable.” Interesting responses that did not have enough mentions to make a full theme of their own are also included here; for example, responses related to helping parents launch their adult children. Also included here are requests for more research on the benefits of working with a planner, how working with a planner may change clients’ attitudes, and the need for resources that can assist in helping a client view the “why” behind financial planning.

Implications

This project highlights the importance of strengthening relationships between advisers and academics. When advisers share the questions they most care about, academics benefit from new and interesting material to research. This paper emphasizes the need for stronger connections between adviser and academic communities and has focused on identifying the themes and research questions that advisers want researchers to explore. This is useful material for current and aspiring academics, yet financial advisers may wonder how they can help bridge the adviser-academic gap.

Advisers should keep in mind that they need not wait until future surveys to make their voices heard. They can proactively connect with academics to explore opportunities for involvement, whether that is through supporting research, guest lecturing, or adjunct teaching (i.e., part-time teaching available at colleges). Because advisers are “in the trenches,” they offer valuable insight for academics and students about the realities of the profession. Continued interaction is crucial, and discovering opportunities for collaboration begins with reaching out and building relationships.

It is also helpful for practitioners to understand that research is only as good as the data used to conduct it. One of the greatest ways that advisers can help academics is by taking time to participate in surveys. While the research team is pleased with the findings of this project, it is expected that the themes and questions advisers will be interested in will change as planners grapple with new challenges and complexities. Advisers are incredibly busy, so the sacrifice of taking time to engage in this important part of the research process is gratefully acknowledged.

Limitations

This research is subject to several limitations. Most importantly, the research question for this project was delivered in conjunction with questions related to financial adviser “pain points.” These pain point questions were asked prior to the open-ended question used for this project, which likely primed respondents to write about research topics related to client psychology, therapy, and crisis events. Furthermore, the survey was primarily marketed through Financial Planning Association email campaigns, though members of the research team also posted the survey to social media (e.g., LinkedIn) and emailed it to individual/group contacts as a means of increasing responses. Posting the survey to social media introduced it to different populations outside of FPA and the financial planning profession. As noted in Table 1, over 90 percent of respondents self-identified as a client-facing adviser (90.65 percent), paraplanner (2.16 percent), in portfolio management (2.16 percent), or in an administrative role (0.72 percent). We also expect that most participants in the study were likely FPA members. Sample size is also a limitation. While 209 unique individuals responded to our survey, only 139 completed it to the extent that the data was usable. Many respondents did not complete the open-ended question needed for this project (i.e., they left the response completely blank). This lack of participation among respondents limits our ability to comprehensively capture the perspective of our sample. Future research would benefit from a more diverse range of financial advisers through exploring additional channels to capture the views and perspectives of the broader financial planning profession.

We would also like to note that in the demographics section of our survey, we failed to include a response choice for “no certification” and did not ask respondents to identify themselves as “practitioner,” “academic,” or “other.” Future iterations should include those descriptives so that researchers know whether responses are coming from practitioners, academics, or others. As mentioned previously, there were many difficult-to-categorize responses. While a collaborative discussion process was used, it is possible that certain biases remain and that other researchers may categorize responses differently than we have here.

Conclusion

This is the first of what we hope will be a regular survey to understand the evolving research interests of practitioners. While there is progress to be made, it is important to recognize that financial planning research already has a precedent of giving voice to the practitioner. In fact, some of financial planning’s most impactful research was developed by those outside academia. For example, Bill Bengen, CFP®, was a sole practitioner specializing in investment management when he produced his groundbreaking research about safe withdrawal rates (popularly known as “the 4 percent rule”; Bengen 1994). Additionally, Jonathan Guyton, CFP®, was a principal at Cornerstone Wealth Advisors and William Klinger was a software development project leader when their 2006 study on decision rules and maximum initial withdrawal rates was published (Guyton and Klinger 2006). Non-academics have profoundly influenced financial planning research and the way practitioners serve their clients today.

Results from this paper will help researchers identify important questions that practitioners want answers to. We believe a stronger partnership between academics and advisers will result in three main benefits: (1) Practitioners can outsource questions they face to researchers with time, energy, and skills to explore solutions; (2) Researchers will have access to interesting and challenging questions that can have near-term impact in the field; and (3) A positive cycle of interactions can grow between the two communities, thereby strengthening the “essential partnership” between practitioner and academic.

While understanding practitioners’ current challenges and questions is important, we also believe in the value of thinking about the challenges and questions of the future. The research process is not short, and it is possible that by the time current topics are studied, advisers may be worried about different issues. We cannot predict the future, but the profession may benefit from carefully considering potentialities and how we can begin researching them today. We imagine a future where practitioners and academics are increasingly aligned, where advisers are excited about the research being produced, and where academics have a long list of relevant, interesting, and impactful research questions informed by practitioners. A survey conducted regularly to understand practitioners’ needs will be one important step to strengthening the “essential partnership” highlighted by Buie and Yeske (2011).

Citation

Sanchez, Donovan, Megan McCoy, Khurram Naveed, and Blake Gray. 2025. “Bridging the Adviser-Academic Gap: A Call to Unite Practitioner Preferences with Academic Research.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (4): 60–75.

References

Ajzen, Icek. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211.

Anderson, Jason, Joanne C. Wu, Ashlyn Rollins-Koons, et al. 2022. “A Decade of Research in the Journal of Financial Planning (2011–2021).” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (9): 70–81.

Archuleta, Kristy L., and Sonya Lutter. 2020. “Utilizing Family Systems Theory in Financial Therapy.” Financial Planning Review 3 (1): e1073.

Asebedo, Sarah D. 2016. “Building Financial Peace: A Conflict Resolution Framework for Money Arguments.” Journal of Financial Therapy 7 (2): 2.

Asebedo, Sarah D. 2019. “Financial Planning Client Interaction Theory (FPCIT).” Journal of Personal Finance 18 (1): 9–23.

Asebedo, Sarah D., and Martin C. Seay. 2015. “From Functioning to Flourishing: Applying Positive Psychology to Financial Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (11): 50–58.

Asebedo, S., and Emily Purdon. 2018. “Planning for Conflict in Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning 31 (10): 48–56.

Bengen, William P. 1994. “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial Planning 7 (4): 171–180.

Bogan, Vicki L., Christopher C. Geczy, and John E. Grable. 2020. “Financial Planning: A Research Agenda for the next Decade.” Financial Planning Review 3 (2): e1094. https://doi.org/10.1002/cfp2.1094.

Bond, Nikki, and Conor D’Arcy. 2021. “The State We’re In.” Money and Mental Health Policy Institute. www.moneyandmentalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/The-State-Were-In-Report-Nov21.pdf

Brammer, M. Lawrence, and Ginger MacDonald. 2002. The Helping Relationship: Process and Skills. 8th ed. London: Pearson.

Britt, S. L., Lawson, D. R., & Haselwood, C. A. 2016. “A Descriptive Analysis of Physiological Stress and Readiness to Change.” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (12): 45–51.

Buie, Elissa, and Dave Yeske. 2011 “Evidence-Based Financial Planning: To Learn . . . Like a CFP.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (11): 38–43.

Byram, Jamie Lynn, M. McCoy, M. Krueger, and John Grable. 2023. Financial Planning Counseling Skills. Erlanger: National Underwriter Company.

Caplan, Nathan. 1979. “The Two-Communities Theory and Knowledge Utilization.” American Behavioral Scientist 22 (3): 459–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276427902200308.

CFP Board. 2021. “CFP® Certification Learning Objectives.” www.cfp.net/-/media/files/cfp-board/cfp-certification/2021-practice-analysis/2021-cfp-certification-learning-objectives.pdf.

CFP Board. 2022. “How the Psychology of Financial Planning Can Benefit Your Clients and Your Practice.” www.cfp.net/knowledge/industry-insights/2022/06/how-the-psychology-of-financial-planning-can-benefit-your-clients-and-your-practice.

Chaffin, Charles R. 2018. Client Psychology. Hoboken: Wiley.

Chatterjee, Swarn, Sonya Lutter, and Dave Yeske, eds. 2023. Psychology of Financial Planning. Cincinnati: ALM.

Clarke, Victoria, and Virginia Braun. 2017. “Thematic Analysis.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (3): 297–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613.

Dubofsky, David, and Lyle Sussman. 2009. “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 22 (8): 48–57.

Ethos. 2022. “With End-of-Life Preparedness, Actions Speak Louder Than Words, Ethos Survey Finds.” www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/with-end-of-life-preparedness-actions-speak-louder-than-words-ethos-survey-finds-301585801.html.

FINRA. n.d. “Addressing and Reporting Financial Exploitation of Senior and Vulnerable Adult Investor.” www.finra.org/rules-guidance/key-topics/senior-investors/elder-abuse-prevention-training.

Finke, Michael S., Wade D. Pfau, and David Blanchett. 2013.”The 4 Percent Rule Is Not Safe in a Low-Yield World.” Journal of Financial Planning 26 (6): 46–55.

Fothergill, Alice. 2000. “Knowledge Transfer between Researchers and Practitioners.” Natural Hazards Review 1(2): 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2000)1:2(91).

Gallo, Jon. 2006. “Creating the Human Moment for Clients in Crisis Situations.” Journal of Financial Planning 19 (12): 46–47, 50.

Goyal, Kirti, and Satish Kumar. 2023. “A Bibliometric Review of Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning Between 1990 and 2022.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 34 (2): 138–168.

Grable, John, Wookjae Heo, and Abed Rabbani. 2015. “Financial Anxiety, Physiological Arousal, and Planning Intention.” Journal of Financial Therapy 5 (2): 2.

Guyton, Jonathan T., and William J. Klinger. 2006. “Decision Rules and Maximum Initial Withdrawal Rates.” Journal of Financial Planning 19 (3): 48–58.

Evans, Katie, Merlyn Holkar, and Nic Murray. 2019. Overstretched, Overdrawn, Underserved: Financial Difficulty and Mental Health at Work. Money and Mental Health Policy Institute.

Johnson, Laura, Yafan Chen, Amanda Stylianou, and Alexandra Arnold. 2022. “Examining the Impact of Economic Abuse on Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review.” BMC Public Health 22 (1): 1014. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13297-4.

Lawson, Derek R., and Bradley T. Klontz. 2017. “Integrating Behavioral Finance, Financial Psychology, and Financial Therapy into the 6-Step Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (7): 48–55.

Lurtz, Meghaan. 2023, Aug 21. “How Niches Improve Advisor Marketing Satisfaction and Efficiency.” Nerd’s Eye View [blog]. www.kitces.com/blog/niches-improve-advisor-marketing/.

Luther, R., L. J. Coleman, M. Kelkar, and G. Foudray. 2018. “Generational Differences in Perceptions of Financial Planners.” Journal of Financial Services Marketing 23: 112–127.

McCoy, Megan, Kenneth J. White, and Xian Yan Chen. 2019. “Exploring How One’s Primary Financial Conversant Varies by Marital Status.” Journal of Financial Therapy 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1193.

McCoy, M., I. Machiz, J. Harris, C. Lynn, D. Lawson,and A. Rollins-Koons. 2022. “The Science of Building Trust and Commitment in Financial Planning: Using Structural Equation Modeling to Examine Antecedents to Trust and Commitment.” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (12): 68–89.

McCoy, Megan, Kimberly Watkins, Kenneth White, Rick Kahler, and Miranda Reiter. 2024. “The Importance of the ‘Client’ Experience for Financial Planning Students: A Qualitative Inquiry of Themes.” Journal of Financial Counseling & Planning 35 (2): 264–275.

McCubbin, Hamilton I., and Joan M. Patterson. 2014. “Family Transitions: Adaptation to Stress.” In Stress and the Family, eds. Hamilton I. McCubbin and Charles R. Figley. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Mitchell, Olivia S., and Stephen P. Utkus. 2006. “How Behavioral Finance Can Inform Retirement Plan Design.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 18 (1): 82–94.

Mizrahi, Terry, Marcia Bayne-Smith, and Martha Lucia Garcia. 2008. “Comparative Perspectives on Interdisciplinary Community Collaboration between Academics and Community Practitioners.” Community Development 39 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330809489665.

Mulvey, John M., and Bala Shetty. 2004 “Financial Planning Via Multi-Stage Stochastic Optimization.” Computers & Operations Research 31 (1): 1–20.

Opiela, Nancy. 2001. “When Misfortune Brings a Client to Your Door.” Journal of Financial Planning 14 (2): 58–66.

Prochaska, James O., and Carlo C. DiClemente. 1983. “Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51 (3): 390–395.

Prochaska, James O., and Wayne F. Velicer. 1997. “The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change.” American Journal of Health Promotion 12 (1): 38–48.

Sterbenz, E., D. Ross, R. Melton, J. Smith, M. McCoy, and B. Pearson. 2021. “Using Scaffolding Learning Theory as a Framework to Enhance Financial Education with Financial Planning Clients." Journal of Financial Planning 34 (12): 70–80.

Wang, Mo, and Junqi Shi. 2014. “Psychological Research on Retirement.” Annual Review of Psychology 65 (1): 209–233.