Journal of Financial Planning: August 2024

Brendan Pheasant, CFP®, ChFC, is a financial planner with Tuyyo Planning Group, LLC, and a doctoral student in personal financial planning at TTU. Brendan’s vision is intelligent, academically based, well-being-centered financial planning.

NOTE: Click on the image below for a PDF version.

This article examines two potential problems with goals presented in the financial planning process and how identifying a client’s underlying needs can help: First, stated goals are restricted to the time horizon the client has considered, which can lead to an overallocation of resources to short-term goals. Second, they can be the client’s best guess at how to achieve another goal rather than the goal itself. Identifying a client’s underlying need can help solve both problems. This article discusses practical steps for financial planners to identify underlying needs in the financial planning process, with examples and a case study.

In his 2013 Ted Talk, Alex Wissner-Gross introduced a concept of intelligence that has inspired my work as a financial planner. Wissner-Gross summarized intelligence as “. . . a physical process that tries to maximize future freedom of action and avoid constraints in its own future” (Wissner-Gross 2013). The concept is that intelligence acts today to increase opportunities to achieve desired goals in the future. On the one hand, this resonates deeply with financial planning. Failure to plan for retirement means fewer choices about what to do in old age. Great retirement planning means clients may be able to live their dreams even in the face of adverse circumstances such as lower-than-expected market returns, increased healthcare costs, or higher taxes. On the other hand, maximizing future freedom of action begs the question, “Maximizing future freedom of action to what?” After all, clients do not value all future freedom of action equally. How do we determine what futures clients value?

The answer is usually goals, but goals have two fundamental problems. First, they are restricted to the time horizon that clients have considered. If goals are predominantly short-term, there could be a risk of overallocating resources to short-term goals, affecting clients’ ability to achieve subsequent goals as time progresses. Second, clients may present goals that are steps to another goal rather than the goal itself. In that case, helping them achieve the stated goal may be less efficient than alternative strategies or, worse, may not help them achieve their actual goal.

This article reviews these potential problems with goals and how identifying clients’ underlying needs can help.

Potential Problems with Goals

Time Horizon

The first problem of goals being limited to the time horizon the client has considered can be illustrated in the following example. Suppose the client is recently married and desires to begin their family by purchasing a house and having children. If they focus on these short-term goals without considering intermediate-term goals such as taking more time off with the birth of each child, purchasing a larger vehicle, or how their expenses will change with childcare and increased healthcare costs, those costs may not be considered in the financial planning process. This could create an overallocation of resources to short-term goals, decreasing the client’s ability to achieve the subsequent goals as the client becomes aware of them.

They Are Not Goals

Problem two is that some of the client’s goals are just steps to another goal and not what the client is actually trying to achieve. This creates two issues. First, if a more efficient, less resource-intensive solution exists to achieve the end goal, financial planners may fail to consider it. Second, the goal may not help the client achieve their end goal.

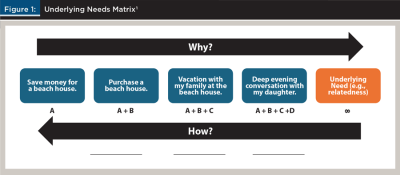

Take, for instance, a client who states that they want to save money to buy a beach house. The financial advice might be to save money for a down payment or earn additional income via a promotion to support the property’s expenses. These solutions may take considerable resources from the client. However, if the financial planner asks why they want to purchase the beach house, they may get an answer such as “to vacation with my family.” Continuing this line of questioning, the financial planner may get a series of responses, as outlined in Figure 1. Eventually, they might get to an answer with no “why”: “I want to have a good relationship with my daughter because I do.” This answer with no “why” is an underlying need. It is the end goal. Everything prior was the client’s best guess for how they would achieve it.

Once the underlying need is understood, it is clear that the beach house is not the most efficient possible solution in terms of resources. In addition, it may not guarantee fulfillment of the underlying need. Purchasing a beach house does not mean the daughter will show up ready to relate to the client.

Underlying Needs

Uncovering underlying needs can help solve these problems with goals by helping identify less resource-intensive solutions that can preserve more resources for future goals and ensure that the solutions that are considered address their end goal, which is the underlying need.

Underlying needs help the financial planner and client consider additional solutions in the following manner. If the financial planner takes the goal “Save money for a beach house” at face value, there is a set of possible solutions, A, which may include saving money in a savings account or brokerage account. By asking why the client would like to achieve the goal, the financial planner arrives at a new goal, illustrated in Figure 1, with each new goal having an additional set of solutions to be considered. Purchasing a beach house has a solution set that includes A + B. Set B may include solutions like selling the client’s original house to purchase the beach house, which may make saving unnecessary. Each subsequent solution set opens new possibilities but does not eliminate solutions from previous sets. Solution set C may include things like renting a beach house. Set D may include evening reservations at a restaurant or the client’s house to build the relationship with their daughter. Each iteration that gets closer to the underlying need consists of more possible solutions requiring different resource levels. An invitation to dinner and purchasing a beach house differ widely in the resources needed. If an alternative solution requires fewer resources than the original, the client will have more resources to reach other goals. This addresses the issue of the presented goal not being the end goal and potentially lowers the risk of overallocating resources to near-term goals.

Uncovering Underlying Needs

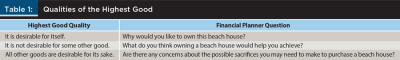

It would be ideal, but possibly impractical, for every financial planner to become an expert in underlying needs. Fortunately, this is unnecessary. In the 300s B.C., philosopher Aristotle proposed an applicable concept called highest good (Kraut 2018). The highest good had three qualities:

- It is desirable for itself.

- It is not desirable for some other good.

- All other goods are desirable for its sake.

These qualities of the highest good can easily be adapted into questions to help uncover underlying needs in the goal-setting process. In the example of the client who says they want a beach house, the qualities of the highest good could be adapted to financial planning questions as shown in Table 1.

These questions can help clients and planners better understand underlying needs and keep the financial planner from sounding like a broken record of “why” questions. It is also not necessary to get to the actual underlying need. Getting one or two iterations closer still opens up many new possible solutions.

Case Study

To understand how all of this works in practice, let us look at a client who presents the following goals in order of importance:

- $1 million home closer to downtown.

- Pay for 100 percent of the average cost of in-state public tuition.

- Retire at age 55 with 100 percent of income.

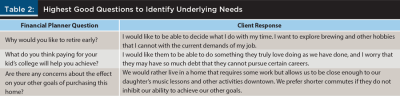

Assuming the client only has the resources to purchase the house, the other goals may go unmet. Instead, the financial planner asks the following questions and receives the responses in Table 2.

It is now evident that retiring early is actually about pursuing other interests. Paying for college is about making sure there are options for their child to do what they love without debt impeding their career choice. The home near downtown is about commute time, and they are willing to purchase a fixer-upper. The financial planner has gotten closer to the underlying needs by asking these questions, opening up new potential solutions.

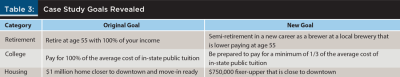

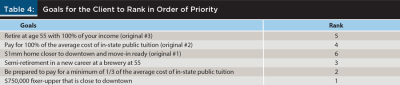

Table 3 displays the newly uncovered goals. The financial planner can then present the original and newly discovered goals for the client to rank in order of priority (Table 4).

The new goals have been ranked higher than the original in all categories, opening new possibilities. The financial advice is articulated in the following manner:

Because you desire to provide an opportunity for your child to pursue a career based on meaning and not out of necessity to pay off debt, I am recommending funding your 529 plan at a minimum level of $X per month with excess savings of $Y being put into a taxable account.

In the short run, this will allow you some liquidity as you fix up your new home. We want to work tax-efficiently to cover a minimum level of likely college expenses without overallocating to your 529 plan, which can only be used for qualified tuition and expenses. If you want to allocate more money from your taxable account to college expense, you are welcome to do this, but if you don’t need to, it will already be where we would want it to facilitate your transition to semi-retirement at the brewery because we cannot easily access your retirement accounts until age 59½.

By discovering the underlying needs, new, less resource-intensive solutions could be considered. The financial planner was able to use the additional resources to help the client address their newly discovered goals, and overallocation to the near-term goal of the house was avoided.

Conclusion

This article discussed some of the shortcomings of clients’ stated goals in the financial planning process and how identifying their underlying need can help. Financial planners do not have to become experts in human needs but, instead, may use questions inspired by Aristotle’s highest good. This process increases the number of solutions that can be considered and decreases the risks from the discussed potential shortcomings of clients’ stated goals.

It is likely that financial planners and clients will discover many other benefits of identifying clients’ underlying needs besides those discussed in this article. Financial planners may find it easier to explain the logic of their recommendations in terms that the client can easily understand because it is connected on the deepest level to what they are trying to accomplish. Couples may find it easier to discuss differences of opinion once they understand the underlying needs behind conflicting positions and goals. Most importantly, however, it keeps the financial plan moving toward a future our clients truly value.

Endnote

- Inspired by the Hierarchical Structure of Personal Projects (Little 2020).

References

Kraut, Richard. 2018. “Aristotle’s Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Summer. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/aristotle-ethics/.

Little, Brian R. 2020. “How Are You Doing, Really? Personal Project Pursuit and Human Flourishing.” Canadian Psychology 61 (2): 140–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000213.

Wissner-Gross, Alex. 2013, November. “A New Equation for Intelligence.” TED Conferences. www.ted.com/talks/alex_wissner_gross_a_new_equation_for_intelligence?language=en.