Journal of Financial Planning: December 2024

Edward F. McQuarrie is professor emeritus at the Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University. His research focuses on market history and retirement income planning; working papers can be found at https://ssrn.com/author=340720.

Acknowledgements: Helpful comments were received from William Bernstein, Allan Roth, and the Bogleheads forum member who posts as #Cruncher.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

A single premium immediate annuity (SPIA) is the simplest and most straightforward kind of life annuity. The client pays a lump sum to an insurance company, which contracts to issue them a fixed monthly payment for as long as they live. If a married couple, the contract can specify that payment continues for as long as either shall live. To cope with the risk of unexpected early demise, most SPIAs are quoted with a limited guarantee of some kind, with 10 years among the most common (Pfau 2019).

The SPIA is conventionally promoted to prospects using language such as, “The only investment you cannot outlive” or “Income guaranteed for life.” Unfortunately, as many planners will recognize, these statements are somewhat misleading. To see the guarantee not on offer, consider this restatement: “This product offers income guaranteed to maintain its real value no matter how long you live.” No such annuity is currently offered here in the United States. No regulated insurance company offers to make CPI-adjusted payments for life. None.1

And yet, all the initial theoretical work in financial economics on life annuities, which found these to be an optimal approach to funding retirement, assumed an inflation-adjusted annuity was on offer. In fact, Milevsky and McQueen (2015) argue that guaranteed payments, which are not inflation-adjusted, are an inferior financial product of questionable value. In an economic system where inflation is almost never absent and can be substantial, all that an SPIA can guarantee is to pay less real income each year, for as long as the purchaser shall live, with the shortfall compounding over time. In short: the greater the feared longevity, the more attractive the life annuity; but the greater the realized longevity, the greater the expected loss in purchasing power.

That is the paradox addressed in this paper: the only financial product guaranteed for life is almost certain to fund less and less spending power the longer the client lives.2

Enter TIPS: Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities. At maturity, these Treasuries pay out the inflation-adjusted principal. During their term, these bonds also pay out an inflation-adjusted coupon. Roth (2022) describes how to construct a ladder of TIPS bonds maturing in successive years. Properly constructed, the ladder will provide a stream of level real payments over the interval selected.

However, TIPS have one crucial limitation with respect to lifetime income planning: the maximum maturity offered is currently 30 years. A TIPS ladder cannot guarantee inflation protection for a life of unknown length, and the younger the clients at the time the ladder is built (e.g., in their 60s rather than 70s), the more likely the ladder runs out before death, leaving the clients with zero income from that source. Moreover, the longer the ladder, the lower the amount of the real payment that can be secured for each year from a given investment.

This special report examines whether a combination of an SPIA with TIPS might produce a superior solution, relative to annuitizing all the funds available, or placing all the funds in a TIPS ladder. Planners can use the model to help clients decide whether to hedge an SPIA with TIPS.

Base Case

Client situations are of course extremely diverse. For the initial evaluation, a single illustrative case is analyzed in detail.

- Clients are a married couple in their early 70s with a joint life expectancy of 20 years.

- The crediting rate on the SPIA is about 5 percent, with a 10-year term certain guarantee.

- Inflation is assumed to be 3 percent.

- The real rate on TIPS is the difference, at 2 percent.

- Given the assumed crediting rate and life expectancy, an SPIA in the amount of $125,000 will produce a fixed income stream of about $10,000 per year.3

One further assumption needs to be made before the hedge can be evaluated. It concerns the amount of “excess life” to be assumed for purposes of hedging. Life expectancy is just that: the statistical expectation or average. Half the lives in the annuitant pool will extend past that expected life.4 The insurance company uses a mortality table to estimate the probability of a member of the pool living one, two … n years longer than average. The mortality table by convention extends to age 120, with non-zero entries all the way through age 119.

Conversely, no TIPS bond with a maturity of 45 years is available in the United States. Even if one were, hedging the payments due from age 95 to age 119, far beyond the life expectancy of this couple, would require a large sum, with a very high probability that the money set aside to hedge the SPIA at an advanced age such as 105, 110, or 115 will not be needed because the annuitants did not reach that age. To illustrate, in terms of the mortality table used for this paper,5 here are some relevant probabilities:

- About 15 percent of couples aged 74 will have one member survive to age 100, an extra six years;

- About 2.6 percent will have one member survive more than 10 years beyond life expectancy, i.e., for 31 years to age 105;

- On the other hand, there is a 44 percent probability of exceeding life expectancy by one year, to age 95.

- Switching frames, there is better than one chance in four that neither member of the couple will make it even to age 90, four years short of life expectancy.

All these survival probabilities will have been factored into the pricing of the SPIA by the insurance company (see Exhibit 4.1 in Pfau 2019 for an illustration). The SPIA can be guaranteed for life to each member of a pool because some annuitants will die young, and very few will live many years past life expectancy. It all nets out within the insurance firm’s accounting. But the individual annuitant, seeking a hedge from TIPS or any other non-annuity product, does not have the luxury of concluding that there is only a 15 percent probability payments will need to be hedged out through age 100; if they live to 100 in their one life, the extended hedge is 100 percent necessary in their case.

Given this uncertainty, any TIPS hedge of an SPIA must be imperfect and incomplete. The question is which risk to take: to over-hedge against mortality, which means more money unspent in TIPS at death and hence, lower annuity payments and a more sparse lifestyle than could otherwise have been funded; or to under-hedge, in which case, real income from the hedged combination will fall abruptly if the client should beat the odds and still be alive when the hedge comes off.

On the assumption the client has other assets that may be used to support spending late in life—i.e., will not annuitize everything—this article evaluates a moderate degree of over-hedging, taking the hedge out six years past life expectancy to age 100. The argument here is primarily psychological: that most clients will believe it highly unlikely that they will live beyond 100. The argument is also from realism: who can know what the needed spending power will be for their centenarian self, decades hence, should such long life be achieved? Maintaining the real spending power initially set in their 70s may be too high if these become the no-go years of Blanchett (2014).

One final assumption: the clients have a fixed sum available for generating an income stream. The total amount available will emerge organically from the initial scenario. It is that total that could have been put all into the SPIA, or all into the TIPS ladder, instead of constructing a hedged combination. And it is these pure alternatives against which the hedged combination will be tested.

Cost of a TIPS Ladder

Table 1 has the following columns: (1) the nominal annuity payment fixed at $10,000 each year; (2) the inflated future cost of a basket of goods that could be purchased at the outset for $10,000; (3) the nominal shortfall each year, as the fixed $10,000 SPIA payment falls further behind the future cost of the $10,000 basket of goods; (4) a divisor, corresponding to the value of one dollar placed in TIPS at the outset and earning the combined rate (2 percent + 3 percent);6 and (5), using that divisor, the amount to be put in that rung of the TIPS ladder at the outset to fund that later year’s nominal shortfall in spending power.

Table 1 indicates $58,890 must be set aside for a TIPS ladder, under an assumed inflation rate of 3 percent, if the real value of the $10,000 annual income from the SPIA is to be maintained through age 100. This is about 47 percent of the amount annuitized.7

Evaluation

Augmented TIPS Ladder, No SPIA

The pure TIPS ladder alternative can be evaluated by entering the real rate of 2 percent into the PMT formula.8 There is now $125,000 + $58,890 = $183,890 available to fund an income stream for the 26 years through age 100. Annual real income from this ladder at 2 percent would be $9,139—decisively inferior to the $10,000 real income maintained in the combination. The SPIA payments, especially in the early years when they have not been greatly eroded by inflation, ease the burden on the TIPS ladder, relative to that ladder having to fund every dollar of income from the outset.

Augmented SPIA, No TIPS Ladder

Here a table set-up is required for clarity. There is $183,890 available to annuitize; this could produce a fixed annuity payment of $14,756. However, the real value of these initially higher payments will immediately begin to decline.

Moreover, a life annuity guarantees payments for life—but only for life. More exactly, payments are guaranteed only for the initial 10 years under the assumptions set forth earlier; if both annuitants have passed away as of 10 years and a day, payments cease. There could not be an SPIA product priced in terms of life expectancy unless insurance companies could calculate the probability of early demise and be confident that early demise will occur often enough to fund continued payments to those who live beyond life expectancy. The probability of early demise must therefore be factored into the evaluation of any unhedged SPIA.

TIPS cannot guarantee income for life, but the SPIA cannot guarantee income for any fixed term beyond the guarantee purchased.9 It is these matched failings that motivated investigation of the hedged combination in the first place.

Survival weighting of the all-SPIA payments begins as soon as the guarantee stops and continues through the entire 26-year span to age 100, and then beyond. For purposes of comparison, this survival weighting has to be applied to the SPIA component of the hedged combination as well. The $10,000 payment from Table 1 will be reduced by the same percentage as the $14,756 received from the all-SPIA solution. However, the shortfall amounts, keyed to the $10,000 payment, and their funding from the TIPS ladder as in Table 1, are locked in for purposes of comparison; the maturing TIPS rungs will be the same as before.

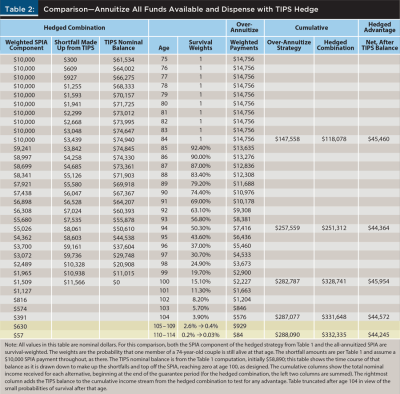

Table 2 lays out the survival-weighted income streams as just described. The rightmost column shows the surplus or deficit of the hedged combination, relative to the all-SPIA solution.

At the expiration of the guarantee, cumulative payments from the hedged combination in Table 1 run almost $30,000 behind the all-SPIA case in Table 2, a substantial sum. However, there remains almost $75,000 (nominal) in the TIPS fund; therefore, the combination produces more wealth, about $45,000. By year 20, at life expectancy, the cumulative income stream from the hedged combination has almost caught up to the all-SPIA sum, and there is still $50,000 in TIPS. At age 100, the TIPS balance goes to zero, but by this point, payments from the combination would have exceeded those received under the all-SPIA solution by about $45,000. After age 100, survival-weighted payments for the all-SPIA solution revert to being greater each year, but the dollar amounts are small in absolute terms; the advantage of the hedged combination erodes through age 114, but not by much.

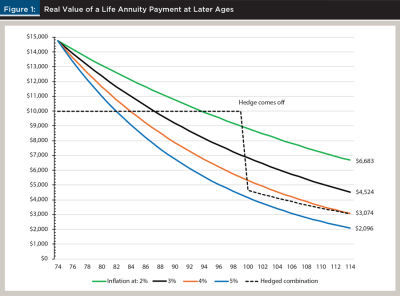

It was convenient in Table 2 to use nominal values to keep the focus on the effects of mortality on the expected value of a life annuity. Figure 1 removes the survival weighting to highlight the effects of inflation on the initially higher, all-SPIA solution. Four levels of inflation are applied against the $14,756 payment. The metric of interest is the number of years required for the higher all-SPIA payment to drop below the $10,000 real value maintained by the hedged combination examined in Table 1. Under 5 percent inflation, the all-SPIA solution drops below the hedged combination at age 84; at the projected 3 percent level, the all-SPIA payments drop below at age 88, after 14 years. Values at the right side of the figure show how far the real value of the $14,756 will have dropped in the event of great longevity.

Inflation compounds relentlessly. It did not take very long for the ever-increasing nominal, inflation-adjusted amounts generated by the combination of an SPIA with TIPS to outrun the initially higher unhedged SPIA payment fixed in amount. The comparison confirms the devastating effects of even a moderate degree of inflation on the fixed payment from an SPIA as the decades pass.

Summary Evaluation

Income guaranteed for life cuts both ways: that income is only guaranteed for life. And it is also fixed for life. The TIPS-hedged combination includes an investment appreciating in nominal terms at 5 percent per year. Annual debiting to top off the SPIA payments does not drop the TIPS balance below its (nominal) starting value until the 19th year (Table 2). By contrast, funds that have been annuitized are no longer invested, and that proved costly indeed in comparison to holding some funds in an investment keyed to inflation.

A high initial SPIA payment is superficially attractive but cannot be guaranteed for very long. In the out years, its expected value declines as the odds increase that the annuitants will both have passed away. Table 2 was constructed to highlight the expected effects of mortality as well as inflation.

Planners can help clients assess the dollar risk of excess life on a survival-weighted basis, which turns out to be surprisingly small.

Robustness

The baseline model was run through a variety of scenarios to test its robustness. Selected outcomes are briefly described in this section.

Inflation Does Not Match Expectations

The base case used 3 percent to reflect the average rate of inflation since 1926 per the Stocks, Bonds, Bills & Inflation yearbook (Ibbotson 2020). But inflation has varied considerably. In the United States, all 30-year periods within 1949–2008 inclusive saw annualized inflation above 4 percent; and all start years from 1960 to 1972 saw 30-year inflation above 5 percent.10 At the other extreme, 30-year periods ending after 2012 saw annualized inflation below 3 percent in the United States, bottoming at 2.25 percent in 2020. Going forward, 2 percent inflation is the rate currently targeted by the Federal Reserve.11

Any shortfall in realized inflation will mean that the hedge can be extended further, past age 100, because not all the amounts in the early maturing rungs will be needed, and the surplus can be reinvested in additional rungs. The more pressing question is what happens if the SPIA proves to be under-hedged for inflation, i.e., if inflation comes in greater than the projected 3 percent. The more severe the shortfall, the greater the impetus for the planner to get in front of the problem by planning for inflation greater than 3 percent. However, as over-hedging grows more extensive, more funds must be reserved for TIPS and less can be annuitized; the effect will be to depress the SPIA payments considerably below what could have been spent with a properly sized (in retrospect) hedge.

Planners need to acquire a good sense of how unexpectedly lower or higher inflation will affect hedge outcomes. They can then explain to clients the risks of under- or over-hedging inflation.

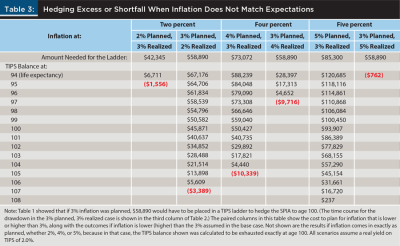

Table 3 compares outcomes for over- or under-hedging inflation. Taking the undershoot first, if the planner sizes the TIPS ladder for 3 percent but inflation comes in at 2 percent, the TIPS hedge can be stretched out to just under age 107. On the other side, realized inflation of 4 percent when 3 percent was the plan will cause the hedge to be exhausted over three years early, at age 96 and change. And if inflation comes in at 5 percent, the hedge sized for 3 percent does not quite last through life expectancy at 94. Conversely, if 5 percent is planned and only 3 percent results, the hedge will last to age 108.

Table 3 makes clear both the potential benefits of over-hedging against inflation, but also the dollar cost to do so. Compared to the $58,890 required to hedge against 3 percent inflation, as in Table 1, to plan for inflation of 5 percent would have required $85,300 to be placed in the TIPS ladder. Adding the $125,000 for annuitization, total funds required would be $210,300.

But there is an unexpected outcome when inflation that high is hedged. A sum of $210,300, placed entirely in a TIPS ladder at a real rate of 2.0 percent, would have funded 26 real annual payments at $10,450—higher than the $10,000 target in the base case for a hedged combination; alternatively, it could have funded the targeted real income of $10,000 for about 27.5 years, almost through age 102.

Turns out, an SPIA payment, eroding in value at a rate as high as 5 percent per year, is a poor use of funds; when inflation is that high, the TIPS ladder is superior at sustaining real income over an interval that 85–90 percent of clients in their mid-70s will fail to outlive.

The conundrum facing the planner has now been brought into focus. The goal was to hedge the SPIA against inflation. After 26 years, even 2 percent inflation will have reduced the real value of the SPIA payment by 40 percent (Figure 1). At 5 percent inflation, the reduction is over 70 percent. If that is the level of inflation that planner and client anticipate, the planner cannot advise that any funds be placed in the SPIA. All the funds should be placed in a TIPS ladder.

Conversely, if planner and client are overly pessimistic and realized inflation comes in less than anticipated, over-hedging occurs, and the consumption that could have been funded with a more ample SPIA is reduced.

The recommendations section will suggest a way to thread this needle.

Alternative Ages for Annuitization

The base case assumed a couple age 74 because their joint life expectancy was almost exactly 20 years, simplifying the initial illustration. A couple whose average age is about 74 (e.g., 75 and 73, or 76 and 72) will also have a life expectancy of about 20 years, and all the illustrations given thus far apply.

This section considers how robust the illustrations are across age groups that are younger or older than the early 70s. For conciseness, annuitization at age 70 versus 79 will be compared to the base case. Joint life expectancy is about three years longer at 70 and about 3.5 years shorter at 79.12 Income from annuitizing $125,000 will accordingly be lower (higher).

An offline analysis shows, unsurprisingly, that the expense of the TIPS hedge taken out to age 100 goes up for younger clients and down for older clients, rising from $58,890 in the base case to $66,281 at age 70, and falling to $49,124 for older clients age 79. Nonetheless, at projected inflation of 3 percent, the hedged combination remains superior to the pure SPIA and all-TIPS alternatives.

What changes with age is the breakeven inflation rate, which, if exceeded, would have pointed to an all-TIPS solution in place of the hedged combination, dispensing with the SPIA altogether. That tipping point was about 4.25 percent for the base case with a 74-year-old couple.13 It falls to 3.96 percent for the younger 70-year-olds and rises to 4.73 percent for the older couple. In short: too much inflation over too long a span renders a fixed payment life annuity a dominated and inferior use of funds.

These results serve as a reminder of how dangerous inflation is to any fixed income source. The younger couple needed to hedge 30 years of fixed payments against inflation out to age 100. That is a lot of time for inflation to compound, destroying the point of the SPIA even at the comparatively low inflation level of 4 percent. The older couple only needs to hedge 21 years to get to age 100, enabling the SPIA in combination with the TIPS to handle higher levels of projected inflation before succumbing to an all-TIPS alternative.

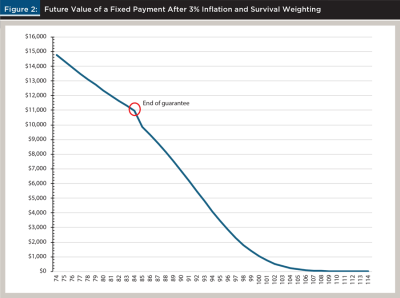

In short: for any planning interval, there is a level of inflation that argues against placing any funds in a fixed source of income such as a life annuity. Perhaps even more sobering is the effect of combining survival-weighting and inflation. Figure 2 shows the real value of the over-annuitization payment of $14,756 from Table 2, weighted by the odds that one member of the couple will still be alive to receive that deflated payment. The figure provides perspective on the expected future value of a fixed nominal income stream guaranteed for life, but only for life.

Extensions

The basic concept of a TIPS ladder to hedge payments fixed for life can be extended beyond the base case, to other forms of fixed payments, and to other approaches to hedging with TIPS.

Pension

All the analyses of the SPIA apply to the typical defined benefit pension as well. However, only the TIPS ladder portion must be purchased in the pension case, presumably from other savings earmarked for retirement. For the client with a pension, the planner can insert the pension payment in place of the $10,000 SPIA payment in Table 1 and recalculate the dollars that must be invested in each rung of the TIPS ladder given the projected rate of inflation.

If the pension includes an escalator clause, such as “inflation rate or 2 percent, whichever is lower,” one need only hedge against projected inflation minus the limit on the escalator clause. Here Table 1 can be adapted by incrementing the first-year pension payment by 2 percent each year and expressing the annual shortfall to be hedged with TIPS as the cost of goods inflating at 3 percent versus the pension payment escalating at 2 percent. Such a hedge will be much less costly than in the base case; the government providing the pension has assumed the risk of inflation up to 2 percent, and the pensioner need merely hedge against inflation in excess of 2 percent.

Alternative Hedging Strategies

A TIPS ladder is the only hedging approach that can guarantee a stream of payments having a specified real value year by year. However, other more approximate hedging strategies using TIPS can be envisioned. The simplest would be to buy a single TIPS bond maturing at life expectancy, with the purchase amount calibrated according to the design of Table 1. Coupon income will suffice to top off the SPIA for the first few years, and then the bond principal can be gradually liquidated as needed.

A more complicated approach might be described as “hedge as you go.” Consider Table 2, with its over-annuitization. If the $10,000 basket of goods represents the expenses that need to be covered, then in the first year $4,456 from the annuity payment is surplus. Those funds could be used to begin purchasing TIPS. The reinvestment versus spending decision can be reviewed each year. If elected, reinvestment would continue until the over-annuitized amount falls short of the inflation-adjusted cost of the basket of goods; from that point, the process reverses and the TIPS accumulation will be drawn down to top off the SPIA payments.

Both these alternatives are in the spirit of the TIPS ladder: that something must be done to address the vulnerability of the SPIA to future inflation. Neither is as exact as a ladder, but the simplicity of the one or the optionality of the other may hold appeal for some clients.

Recommendations

The stand-alone life annuity emerges from this analysis as a fundamentally flawed product under an inflationary regime. Its distinctive promise of “income you cannot outlive” entails a loss of real value that only grows greater the longer that life lasts.

A TIPS ladder, by contrast, is the only product that can guarantee a level stream of real income no matter what happens to inflation and interest rates. It has one key shortcoming: no ladder longer than 30 years can be constructed in the United States today.

In retrospect, the solution appears obvious: to combine these two products with their offsetting strengths and weaknesses. The primary recommendation is to pair an SPIA and a TIPS ladder in a ratio of approximately two-to-one, i.e., to set aside half against the amount annuitized in TIPS, with the exact amounts determined by the projected rate of inflation, the real rate available across the TIPS yield curve at the time, and the clients’ ages.

Inflation projections should emerge from discussion with the clients. Those who are more fearful of inflation can be shown the cost of insuring against, say, 4 percent inflation, and the reduction of annuity income that results, given a fixed sum available. The planner should also explain how, as planned inflation increases past 4 percent, the SPIA begins to lose point, especially for younger clients. Conversely, I would discourage planning for inflation much less than 3 percent; realized inflation near 2 percent has been the exception, not the rule, since the gold standard lapsed in 1934.

Inflation expectations and fears need to emerge from dialogue with clients. But if planners are going to recommend this hedged combination more than once in a great while, it is incumbent upon planners to familiarize themselves with mortality tables and the shape of the mortality curve. The typical client has no clue about actuarial statistics nor is there any reason to expect them to research survival probabilities on their own. That task properly falls on the planner. A good place to start is IRS publications explaining the actuarial science behind required minimum distributions, which by statute must reflect current mortality statistics. As a bonus, these IRS publications will give the planner a better feel for how RMD amounts are likely to increase over the life span (McQuarrie 2022b).

Given a good grasp of mortality statistics, in combination with the analyses laid out in this special report, the planner can provide clients with a valuable design service that few could manage on their own: construction of an inflation-hedged life annuity.

Conclusion

This report focused on the client worried about longevity risk, who comes to the planner predisposed to purchase a life annuity. The recommendation was to hedge the life annuity with TIPS, and the analysis showed the superiority of a hedged combination to either the SPIA or TIPS alone, given moderate inflation.

Consider instead the client who is primarily worried about inflation risk. Matters are not entirely symmetrical when the starting point is swapped in this way. A life annuity must be adjudged more risky than a TIPS ladder. No guarantee from a private firm, and no state guarantee fund, can be as free of risk as a bond backed by the full faith and credit of the United States Treasury. In addition, payments from an SPIA will be subject to state tax, which can run as high as 13.3 percent in California. And, as shown in this article, if inflation runs hot enough, the SPIA becomes a poor use of funds, relative to holding more TIPS.

In summary, the client considering a life annuity should be urged to hedge with TIPS. Inflation is uniquely dangerous to fixed payment streams. But the client who is primarily fearful of inflation and seeking protection from TIPS cannot be urged so strongly to take out an SPIA as a supplemental hedge. A more diffident approach is required of the planner in discussing the hedging potential of adding an SPIA to a TIPS ladder. If the client remains unconcerned with longevity risk after being acquainted with mortality statistics—or chooses to prioritize legacy goals—best not to urge a life annuity as a supplement to the TIPS ladder.

Endnotes

- Such products were offered through about 2019 and continue to be offered in some nations outside the United States. Currently, only escalator clauses are on offer. These allow the annuitant to accept a lower initial payment in return for having payments increase each year at a fixed percentage. If inflation comes in higher than expected, as in 2021 and 2022, there is a reduction in real income, same as a standard SPIA. And if the annuitant dies young, only the lower, un-escalated payments will have been received.

- The purchase decision is all the more fraught because most clients will already have the equivalent of an inflation-adjusted life annuity in the form of their Social Security payments. Well-paid professionals who have deferred Social Security to age 70 currently receive more than $50,000 per year, equivalent to annuitizing over $1 million, depending on the life expectancy and inflation rate assumed.

- The annuity values roughly correspond to those found at www.immediateannuities.com in mid-2024, and the real yield on TIPS has also recently been about 2 percent. There can be no certainty that $125,000 would produce exactly $10,000 in annual payments in the future, or that TIPS will yield 2 percent when annuities are crediting 5 percent. The $10,000 payment on $125,000 is simply a plausible benchmark for clients about this age.

- Technically, about half the life-years. See https://lifeexpectancy.org for a discussion of key terms and calculations.

- This is the joint life expectancy table from IRS Publication 590, as revised for 2022. It uses annuitant life expectancy rather than life expectancy in the general population as compiled by the Social Security Administration (annuitants live longer). The derivation of the table from mortality statistics is explained at www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/11/12/2020-24723/updated-life-expectancy-and-distribution-period-tables-used-for-purposes-of-determining-minimum.

- Technically, this should be 1.03 × 1.02, or 5.06 percent; I round down to make the results a bit more conservative.

- For reference, if the real rate on TIPS was only 1 percent, the needed amount would increase to $68,977, or 55 percent of the amount annuitized. The amount will also vary with the assumed inflation rate; see Table 3.

- The PMT formula with period set equal to life expectancy only gives an approximation of what the insurer might be able to pay on an SPIA; see Promislow (2015) for an explanation, and appendix E in McQuarrie (2022a) for an evaluation in dollars of that approximation in an illustrative case.

- Under the mortality assumptions, the probability is 94.36 percent that at least one of a 74-year-old couple will still be alive after 10 years, making the 10-year guarantee inexpensive for the insurance company to offer.

- All inflation figures in this paper are calculated from the non-seasonally adjusted CPI-U series made available by the St. Louis branch of the Federal Reserve (series name CPIAUCNS).

- However, the targeted rate is not the realized CPI-U that is used to adjust TIPS values but the run rate on the core Personal Consumption Expenditures index.

- Each additional year of life reduces life expectancy for those surviving by less than 1 years.

- The breakeven inflation rate is the value which, using a ladder alone, produces real payments out to 100 exactly equal to the $10,000.

References

Blanchett, D. 2014. “Exploring the Retirement Consumption Puzzle.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (5): 34.

Ibbotson, R., 2020. Stocks, Bonds, Bills & Inflation. Chicago: Duff & Phelps.

McQuarrie, E. F. 2022a. “The Annuity Wager: Can Bonds Outperform a Life Annuity?” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4160167.

McQuarrie, E. F. 2022b. “Will Required Minimum Distributions Exhaust My Savings and Leave Me in Penury?” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4001986.

Milevsky, M. A. and A. C. McQueen. 2015. Pensionize Your Nest Egg (2nd. Edition). NY: Wiley.

Pfau, W. D. 2019. Safety-First Retirement Planning. Virginia: Retirement Researcher Media.

Promislow, S. D. 2015. Fundamentals of Actuarial Mathematics (3rd ed.). NY: Wiley.

Roth, A. 2022, October 24. “The 4 Percent Rule Just Became a Whole Lot Easier.” Advisor Perspectives. www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2022/10/24/the-4-rule-just-became-a-whole-lot-easier.