Journal of Financial Planning: January 2025

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- Limited research exists on the effectiveness of intersession communication, although one preliminary study suggests reaching out to clients between sessions may benefit both clients and planners.

- The theory of polymedia posits that using multiple communication channels (e.g., email, phone, text) between financial planning meetings may create a “web of support” for clients leading to better outcomes. However, planners need to be aware of the socio-emotional consequences of that choice.

- Other writings suggest that too much communication from their planner may cause clients to feel stressed, overwhelmed, or anxious. Furthermore, prior research suggests financial anxiety influences how clients perceive their planner’s communication.

- Using structural equation modeling, this study assessed the cumulative effects of different modes of communication methods used between planning sessions, as well as the moderating impact of financial anxiety.

- Results did suggest that combining at least three methods of communication and personalizing those communications leads to greater trust, commitment, and satisfaction with their financial planner.

- Financial anxiety weakens the positive impact of a strong web of support on trust and satisfaction.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT-I, is an assistant professor of personal financial planning at Kansas State University. She serves on the board of directors for the Financial Therapy Association. She is also the co-editor of Financial Planning Review.

Ashlyn Rollins-Koons, Ph.D., CFP®, is a financial adviser in Northern California. Ashlyn’s research interests are in behavioral finance, financial technology, housing, and family financial socialization.

JOIN IN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Technology has inundated us with ways we can connect with friends, family, and even clients. It is not uncommon for practitioners to email, have a phone call, and meet with the same clients all within the same week. The theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013) posits that when used effectively, these communication outlets can create a web of support for clients. Cheng, Browning, and Gibson (2017) found evidence for the web of support when they discovered that frequent communication through phone calls, texts, and emails is related to an increase in trust with their planner. Despite the possibility of the web of support that can be developed, there are also potential pitfalls to our decision-making around communication for practitioners. For example, Kitces and Richards (2019) caution financial professionals against excessive communication around complex financial matters, suggesting it may cause clients to feel more stressed. This is important to note as research has found that financial anxiety can lead to avoiding financial planning sessions, which also may negatively impact trust and commitment (Grable, Heo, and Rabbani 2015).

In addition to the assumption of the web of support, the theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013) also posits that the choice of communication channel will have a direct impact on your relationship with your client despite your discipline (Archuleta et al. 2021). There is an underlying ethical implication to what type of communication modality we use to express our thoughts to others. The decision of whether to text, email, call, or meet in person impacts how the message is received by clients. A modern-day analogy can be found in Britney Spears’s memoir where she described how Justin Timberlake broke up with her by text instead of in person or at least with a phone call (Spears 2023). Similarly, our decisions to communicate with clients via email, text, phone call, or even social media (referred to henceforth as intersession communication) will shape their emotional reaction to the content we are sharing with them.

Intersession communication may be even more important within the arena of financial planning. After all, “money conversations in any format are challenging as they have the potential for an array of emotions, psychological responses, and relational processes such as stress, anxiety, and conflict” (Archuleta et al. 2021, 82). Our paper will explore whether intersession communication aids or hinders the fostering of trust, commitment, and satisfaction for financial planning clients and if it will provide tangible implications for practitioners. It also moderates this relationship with financial anxiety to see the impact a client’s financial anxiety levels may have on the dynamics as hypothesized by the aforementioned writing of Kitces and Richards (2019). In summary, the research questions that framed this study are:

- Does engaging clients in between sessions in financial planning aid in client outcomes?

- Is it dependent on what type of contact (e.g., texts versus social media)?

- Will more contact between sessions create a web of support for the client?

- Does this use of a web of support create trust and commitment?

- Is it moderated by the client’s level of financial anxiety?

Literature Review

The theory of polymedia (Madianou and Miller 2013) was developed to understand the multifaceted nature of human interaction across diverse media channels. At its core lie several fundamental assumptions.

First is the assumption of media plurality, which posits that modern communication environments are characterized by multiple media channels and platforms. From traditional modes such as face-to-face conversation and written correspondence to digital realms including email, social media, and video conferencing, the proliferation of media options offers a kaleidoscope of communicative possibilities (Madianou and Miller 2013).

Next, the theory underscores the complementarity of different communication channels, rejecting the notion of isolation in favor of synergy. Each channel possesses unique affordances and strengths, allowing individuals to craft tailored communication strategies that align with their goals, contexts, and audience preferences (Madianou and Miller 2013).

The next inherent assumption of the theory is the agency and autonomy of users in navigating the media landscape. Individuals exercise discretion in selecting and utilizing communication channels based on personal preferences, situational factors, and communicative objectives. This choice results in socio-emotional consequences, such as the mode of communication feeling too impersonal for the content of the communication (Archuleta et al. 2021).

Furthermore, the theory of polymedia acknowledges the polycentric nature of communication practices, recognizing the presence of multiple centers of communication activity and interaction. This concept emphasizes the diversity and flexibility of communication processes, recognizing that communication occurs across various channels, actors, and contexts simultaneously (Madianou and Miller 2013).

The final assumption is the interconnectedness and interactivity of communication channels, which can facilitate the fluid exchanges of information, feedback, and meaning.

When practitioners embrace and understand the five assumptions, the theory posits it will create “a web of support” for clients (Archuleta et al. 2021; Madianou and Miller 2013). As a financial planner, leveraging diverse communication channels tailored to clients’ needs and preferences should result in clients who are more satisfied with their relationship with their planner. For example, face-to-face meetings can focus on personalized guidance and advice, emails can be used to share informative articles, and phone calls and virtual meetings offer opportunities for more intimate and personalized interactions.

There has been limited empirical research on the impact of intersession communication on financial planning outcomes. One notable exception was Cheng, Browning, and Gibson (2017) who found that intersession communication was beneficial for both the clients and their planners. More specifically, Cheng, Browning, and Gibson (2017) discussed how regular communication through meetings and personalized emails and cards resulted in clients feeling more satisfied, trusting, and committed to their planner, whereas it benefited planners by enabling “them to better understand their clients’ values and goals, as well as identify changing household demographics and new information that may affect their clients’ service needs” (7).

Although Cheng, Browning, and Gibson (2017) provide support for intersession communication, there are restrictions based on regulations of communication in financial services. In fact, Tharp (2020) found some preliminary evidence that planners may be utilizing communication channels based on which mediums are less regulated, rather than what is best for the client. This has important implications through the lens of the theory of polymedia as the decision on what communication channel should be based on the socio-emotional consequences of the choice rather than based on which channel is less regulated (Madianou and Miller 2013; Tharp 2020). This is where it is also important to reiterate that using the wrong platforms can have a disastrous impact too, where clients may actually become more anxious about their financial situation when communication is not individualized to their particular needs (Kitces and Richards 2019).

This concept of how intersession communication is related to financial anxiety is interesting. First, it is important to define financial anxiety. Financial anxiety has been defined as persistent ruminations about one’s financial state, regardless of the presence of external pressures (Archuleta, Dale, and Spann 2013; Grable, Heo, and Rabbani 2015; Shapiro and Burchell 2012). This is distinct from the concept of financial stress, which is the perception that one lacks sufficient funds to meet their financial demands and cover essential expenses (Heo, Lee, and Rabbani 2021). Financial stress is typically based on an objective evaluation of financial resources and is time-bound, while financial anxiety occurs over a long period of time and may occur without the overt signs of financial struggles. This distinction is important to understand, as financial planning clients tend to have higher net worth and more means than the general public, but prior studies have found that many clients still exhibit symptoms of financial anxiety (Anderson, Sharpe, McCoy, and Lawson 2022). Since research has found that financial anxiety inhibits our ability to hear, understand, and process information (Grable, Heo, and Rabbani 2015), it may inhibit how a client receives communication from their planner. Thus, this study seeks to understand if the client’s financial anxiety levels may moderate the relationship between intersession communication and client outcomes (i.e., trust, commitment, and satisfaction).

Methods

Data and Sample

A survey was administered to clients of financial planners in Canada via a panel company (Precision Data). From the initial set of 2,925 respondents, discrepancies in data pertaining to key screening questions resulted in a reduction of the sample size to 2,783. Within this cohort, 1,246 respondents indicated they did not engage with a financial planner. Conversely, 1,537 acknowledged interactions with financial planners. A follow-up question was posed to this subset of 1,537 to obtain further details on their experiences. Six respondents abstained from this question, resulting in a sample of 1,531. The data for the current study focused on those who use financial planners for more than only investment services (e.g., they also see their planner for other services such as retirement or tax planning), resulting in a sample size of 633. Those who indicated their planner only used “other” communication methods and did not specify a category were also excluded, which brought the final N to 626 respondents. The sample was almost evenly divided between men (52 percent) and women (48 percent). More than half of the sample had incomes below $100,000 with 20 percent of the total sample reporting an income below $50,000. Not quite 30 percent of respondents in the sample had incomes between $100,000 and $150,000, and the remainder reported incomes greater than $150,000. The mean age of the sample was about 52 years old. The youngest respondent was 18 years old, and the oldest respondent was 89 years old.

Variable Measurements

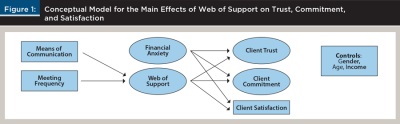

Both single-item questions and scales are used to measure means of communication, web of support, financial anxiety, client trust, client commitment, and client satisfaction. The control variables in this study include gender, income, and age. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted for each of the latent variables. See Figure 1 for the conceptual model.

Dependent Variables

There are three dependent variables of interest in this study: client trust, commitment, and satisfaction.

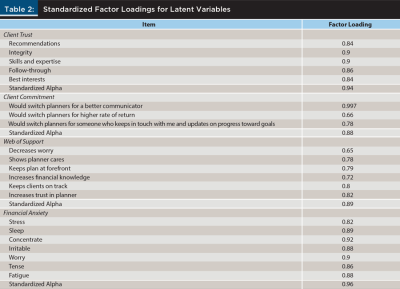

Client trust. Client trust is a latent variable created by Sharpe et al. (2007) as a five-item trust scale. Respondents rated their agreement (where 0 = disagree and 4 = agree) with the following: (a) confidence in their financial planner’s recommendations, (b) confidence in their financial planner’s integrity, (c) confidence in their financial planner’s financial skills and expertise, (d) ability to rely on their financial planner to follow through on their commitments, and (e) trust they have that their financial planner will act in their best interests. The results for the CFA indicated good model fit (X2 [3] = .89, p = .83; RMSEA = 0.00; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.002; TLI = 1.00). Standardized factor loadings ranged from .85 to .89, and alpha was .94.

Client commitment. The second outcome variable of interest was client commitment, which was also a latent construct developed from three of Sharpe et al.’s (2007) commitment scale items. Initially, 0 indicated disagreement and 4 indicated agreement with the following: (a) “I would switch from my current financial planner if I could find someone who is a better communicator,” (b) “I would switch from my current financial planner if I could find someone who could earn a higher rate of return,” and (c) “I would switch from my current financial planner if I could find someone who is better at keeping in touch with me and letting me know how I’m progressing toward my goals.” This was reverse coded in order to have lower scores indicate lower levels of commitment and higher scores to indicate stronger client commitment. Since this was a three-item measure, the construct was just identified and model fit statistics were not available (Kline 2016). The standardized factor loadings from the CFAs ranged from .76 to .87, and the alpha was .88.

Client satisfaction. The last outcome variable was an observed variable to measure how satisfied clients are with their relationship with their financial planner, where 0 = extremely dissatisfied and 4 = extremely satisfied.

Independent Variables

Means of communication. There are many different ways financial planners communicate with their clients between meetings. Clients were asked to select from a list of options how their planner communicates with them between financial planning meetings, which included phone calls, group emails or texts, personalized emails or texts, newsletters, social media or podcasts, other communication, or no interim communications. Only eight respondents selected “other” as an option, so these were excluded.

The groups for this variable were organized first from the least communication to most communication and then by the least personal methods of communication to most. These eight groupings were as follows: (a) those who did not receive any interim communication between meetings, (b) those who received only one method of mass communication or two methods of mass communication, (c) those who only received personalized emails or texts, (d) those who received only phone calls, (e) those who received a personalized email or text and one method of mass communication, (f) those who received phone calls and one method of mass communication, (g) those who received phone calls and personalized emails or texts, and (h) those who were contacted in three or more ways. Dummy variables were created to examine the differences between groups.

The frequency of meetings may also be an important contributor. This study included a variable measuring the frequency of in-person meetings and another variable measuring the frequency of virtual meetings. The survey asked respondents to report the frequency of their in-person and virtual meetings. Respondents could choose from never (in person or virtual), annually, quarterly, monthly, or other. Those who responded “other” were manually sorted into the corresponding category. This resulted in each variable having four categories: (a) never meet or inconsistently meet, (b) annual meetings, (c) meet more than once a year, and (d) meet monthly.

Web of support. Clients were asked how impactful their planners’ methods of connecting between meetings are to them. This web of support looks at how the above referenced communication methods influence client’s perceptions on the following items: (a) decreasing worry about finances, (b) showing the planner cares about their well-being, (c) keeps their plan at the forefront of their minds, (d) increases financial knowledge, (e) keeps clients on track toward meeting their goals, and (f) increases trust in their planner. For each item, 0 indicated disagreement while 4 indicated agreement. Web of support was a latent construct exhibiting good model fit statistics from the CFA (X2 [7] = 14.46, p = .04; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.996; SRMR = 0.01; TLI = 0.99). The standardized factor loadings were all between .64 and .82, and alpha was .89.

Moderator

The moderator for this study was financial anxiety, which was a latent variable that used the financial anxiety scale developed by Archuleta, Dale, and Spann (2013). On a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always), clients rated their experience of the following: (a) feel anxious about their financial situation, (b) have difficulty sleeping because of their financial situation, (c) have difficulty concentrating on their studies/work because of their financial situation, (d) are more irritable because of their financial situation, (e) have difficulty controlling their worries about their financial situation, (f) their muscles feel tense because of worries about their financial situation, and (g) they felt fatigued because they worry about their financial situation.

The initial CFA produced acceptable model fit statistics (X2 [14] = 165.21, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.13; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.02; TLI = 0.95). The modification indices indicated that muscles feeling tense should be correlated with fatigue and stress, stress should be correlated with ability to concentrate, and worry should be correlated with ability to concentrate and irritability. These correlations notably improved the fit statistics for the latent construct (X2 [9] = 18.82, p = .03; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.998; SRMR = 0.01, TLI = 0.995). The chi-square difference test provided further evidence for increased model fit (X2 diff [5] = 146.39, p < .05). The standardized factor loadings for the final latent construct were between .82 and .92, and the alpha was .96.

Analysis

The data was coded and prepared in STATA/SE 17.0, and the analysis used structural equation modeling (SEM) for the results using MPlus 8.8. To test the interaction effect between the client’s web of support and financial anxiety on the outcome variables, a latent moderated structural equation (LMS) two-step method was used. First, descriptive statistics are discussed below for the dependent and independent variables. Second, the measurement model used the CFAs for the main predictor variables to evaluate the overall model fit. The interaction term is not included in the measurement model (Maslowsky, Jager, and Hemken 2015; Muthén and Muthén 2017). Following the measurement model, the full structural model without the interaction term is estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator. This model is referred to as Model 0. Next, a structural model with the interaction term is estimated, referred to as Model 1. The xwith command was used to estimate the LMS model (Model 1), and the ML estimator was also used. The variables were standardized to report standardized results.

Model Fit Testing

The unconstrained model chi-square test of model fit, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI) were used to evaluate model fit statistics for Model 0. While there is no way to determine whether the model with the latent interaction (Model 1) is worse or equal to Model 0, the log-likelihood ratio test can be used to evaluate whether Model 1 also exhibits good model fit (Maslowsky, Jager, and Hemken 2015). The equation used for the log likelihood ratio test is described in equation 1, and the values used for the test are labeled “H0 value” in Mplus (Maslowsky, Jager, and Hemken 2015).

D = –2[(log-likelihood for Model 0) –

(log-likelihood for Model 1)] (1)

Results

Descriptive Statistics

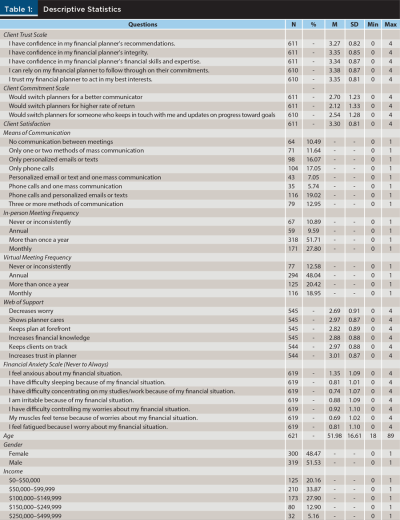

The descriptive statistics and each latent variable indicator can be found in Table 1. Respondent trust scores were relatively high for each indicator. Client commitment scores were slightly lower, with respondents indicating they would be less committed especially if they could find someone who could offer a higher rate of return (M = 2.12) or would do a better job keeping in touch and updating them on their progress (M = 2.54). Clients appear to be satisfied with their planner in general, with a mean score of 3.30 (SD = 0.81).

About 10 percent of clients did not receive any communication from their planner between meetings. Almost 45 percent of clients received one type of any communication or two types of mass communication from their planner between meetings. About 13 percent received either a phone call or a personalized email or text and mass communication, and 19 percent received phone calls and personalized emails or texts. Finally, just under 13 percent received three or more methods of communication between meetings. Nearly 80 percent of clients met with their planner in person more than once a year or monthly. For virtual meeting frequency, clients were more likely to meet annually (48 percent) or more than once a year but less than monthly (20 percent).

When asked about how interim communication strategies affected a client’s web of support, clients reported that the methods of communication most impacted their sense of whether their planner cares for them and keeps them on track (mean score of 2.97) and increases trust (mean score of 3.01). Clients also reported relatively low levels of financial anxiety, with feeling anxious about their financial situation receiving the highest mean score of 1.35 (SD = 1.09).

Model 0

Measurement Model

Three latent variables were used in the measurement model for Model 0—client trust, client commitment, and the client’s web of support. The initial measurement model exhibited good model fit statistics (X2 [174] = 423.78, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.04; TLI = 0.97). While there is some discussion on what constitutes strong model fit, common thresholds for excellent model fit are 0.05 or less for SRMR and RMSEA and 0.95 or greater for TLI and CFI (Kenny 2015; Kline 2016). The modification fit indices indicated that for the client commitment scale, better progress reports and better returns should be correlated. Model fit improved as a result (X2 [173] = 381.39, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.04; TLI = 0.98). A chi-square difference test also indicated significant improvement of this revised model (X2 diff [1] = 42.39, p < .001). Table 2 reports the factor loadings, which were all within acceptable ranges (Kline 2016). Since the CFAs and measurement model were satisfactory, the full structural model was then estimated (Kline 2016).

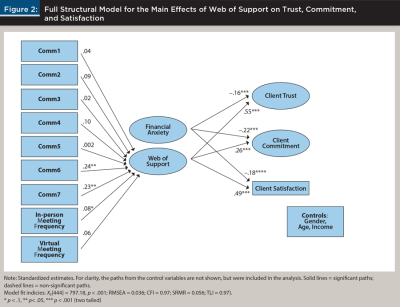

Structural Model

Figure 2 shows the full structural model for this study with the significant paths. The control variables were included on each path, resulting in a final model that exhibited strong model fit statistics (X2 [444] = 797.18, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.036; CFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.056; TLI = 0.97). The model explained 44 percent of the variance in client trust (R2 = 0.44, SE = 0.04, p < .001), 30 percent of the variance in client commitment (R2 = 0.30, SE = 0.03, p < .001), and 32 percent of the variance in client satisfaction (R2 = 0.32, SE = 0.03, p < .001).

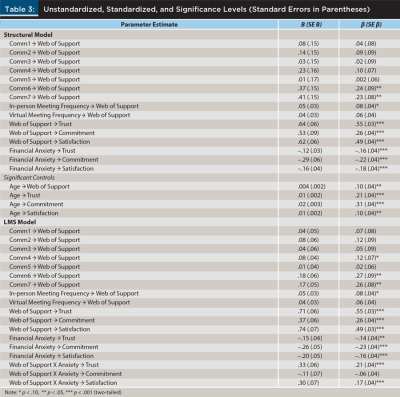

Table 3 reports the standardized and unstandardized results of Model 0 and Model 1, as will be discussed below. Standardized results are reported herein. Only age was significant among the control variables on web of support (b = –.053, p = .04), client trust (b = .281, p < .001), client commitment (b = .405, p < .001), and client satisfaction (b = .184, p < .001).

All hypothesized paths were significant in the full structural model. Clients whose planners used three or more methods of communication were expected to have a greater web of support (b = .231, p < .05). The frequency of how often a client meets with their planner in person is also related to their web of support (b = .053, p < .1). Similarly, those who received personalized phone calls and personalized emails or texts also were expected to have a greater web of support (b = .240, p < .05). An increased web of support led to greater client trust (b = .552, p < .001), client commitment (b = .264, p < .001) and client satisfaction (b = .493, p < .001). Anxiety was negatively related to client trust (b = –.156, p < .001), client commitment (b = –.215, p < .001), and client satisfaction (b = –.176, p < .001).

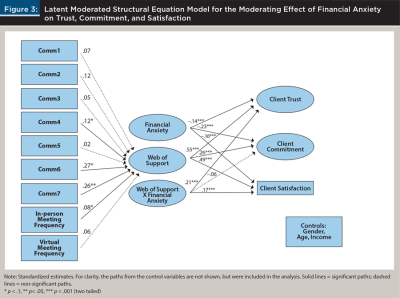

Model 1

Using Equation 1 as described previously, the log likelihood ratio test indicated that Model 0 did exhibit a loss of fit compared to Model 1 (D(3) = 2,879.42), meaning Model 1 can be assumed to exhibit good model fit as well. See Figure 3 for the LMS model. The results from the LMS model (see Table 2) showed there were significant direct effects between web of support and client trust, client commitment, and client satisfaction. There were also significant direct effects between financial anxiety and client trust, client commitment, and client satisfaction. In terms of the moderation analysis, anxiety was found to moderate the relationship between web of support and client trust (b = .210, p < .001) and the relationship between web of support and client satisfaction (b = .165, p < .001).

Discussion

This study’s results provide evidence that communication technologies and strategies are important to developing a client’s web of support. Clients who receive more intermittent communication, especially those who receive three or more methods of communication and more personalized communications, are more likely to perceive a greater web of support as measured by their reports of feeling that their planner cares about their well-being or increasing financial knowledge. The results suggest that the positive outcomes associated with these communication strategies build client trust, commitment, and satisfaction. These initial results support the claim that planners need to communicate frequently and use multiple communication methods to improve a client’s sense of support and client outcomes and provide further support that intersession communication is important to the planner–client relationship (Cheng, Browning, and Gibson 2017).

Yet, the moderation analysis reveals that financial anxiety may derail these communication efforts. While the associations between a client’s web of support and client trust and satisfaction were still positive, financial anxiety appears to reduce the strength of these relationships. This suggests that while planners still need to communicate frequently and personally with clients, financially anxious clients may need extra attention to improve their web of support and, consequently, client outcomes. This is in line with prior research that has shown that financial anxiety hampers clients’ ability to receive information and may impact levels of trust (Grable, Heo, and Rabbani 2015).

Implications

Our findings suggest that intersession communication is essential in building rapport and commitment with clients. A troubling finding from our sample is that 10 percent of planners did not complete any intersession communications with clients. The absence of intersession communication could potentially negatively impact their client’s trust and commitment in the planner, but also negatively impact the planners’ ability to understand their clients’ needs and values (Cheng, Browning, and Gibson 2017). Planners need to find ways of reaching out to their clients, and AI tools can facilitate this intersession communication. In fact, Morgan Stanley recently announced that it was testing the use of AI to create draft summaries of planning meetings, sending follow-up emails, and scheduling events (Rosenberg 2024). Or perhaps, planners can use AI in different ways in their practice—such as automatically sending emails and pushing out social posts to clients when notable laws change or important deadlines are approaching—to provide them with more time to create personalized intersession communications that facilitate the positive outcomes described in our results.

The finding that financial anxiety reduces the power of intersession communication also holds important implications for clients. Anxiety can often manifest in a variety of ways that many planners may not be trained to notice. Anxious individuals do not always present as someone calling incessantly or biting their nails in the waiting room. Anxiety can manifest as avoidant behaviors so the most anxious clients may not return phone calls or attend planning sessions (Eustis et al. 2020). Anxiety can also manifest as anger and frustration, so the client who snaps about the traffic may actually be experiencing anxiety around their finances and does not have the emotional intelligence needed to share their anxiety with their planner (Asberg 2018). Planners need to be intentional about providing financial anxiety scales such as the scale used in this study by Archuleta, Dale, and Spann (2013) to assess financial anxiety in their clients and create a plan for attending to the anxiety. Future research should also center around what method of communication is best for financially anxious clients to ensure the communication mode does not increase their anxiety levels and/or negatively impact the client–planner relationship.

Limitations

Several limitations should be discussed regarding this study. The data is specific to Canadians, which is a strength and a limitation. Canadian data is relatively understudied, and this research provides an interesting insight into Canadian clients. However, future studies could examine other countries and cultures. The demographic data also was skewed heavily toward White respondents. The respondents in this data also reported on average high levels of trust and low levels of financial anxiety, which may not be representative of the general Canadian population. In addition, future studies would benefit from experimental design to examine which types of communication modes work best with what types of communication in line with the proposition of the theory of polymedia that there is a socio-emotional cost to the decision of whether to pick up the phone or shoot a quick email (Madianou and Miller 2013).

Conclusion

This study examined how utilizing various communication tools and strategies enhanced the support system for financial planning clients. It demonstrated that regular, personalized communication through different channels, such as email, phone calls, or video chats, significantly improved clients’ sense of support. This approach increased trust and satisfaction, strengthening the relationship between the planner and the client (Cheng, Browning, and Gibson 2017). Some may have argued that personalizing communication requires too much time and effort. Yet, the evidence from this study supported its effectiveness in aiding clients, indicating that the investment was worthwhile (Rosenberg 2024). There may be space for financial planners to incorporate new technologies, like artificial intelligence (AI) to automate routine tasks, allowing planners to concentrate on creating personalized messages that cater to the specific concerns of each client. This not only strengthens the client support network but also improves planner–client relationships (Rosenberg 2024). However, the results of this study also pointed out that clients with financial anxiety might not have experienced the full benefits of these communication strategies. More research is needed to understand how to tailor intersession communication to avoid messages that increase financial anxiety and what channels of communication will improve client outcomes regardless of financial anxiety levels (Grable, Heo, and Rabbani 2015).

Citation

McCoy, Megan, and Ashlyn Rollins-Koons. 2025. “Building Trust, Commitment, and Satisfaction Through Effective Intersession Communication: The Moderating Effect of Financial Anxiety.” Journal of Financial Planning 38 (1): 82–96.

References

Anderson, Carol, Deanna Sharpe, Megan McCoy, and Derek Lawson. 2022. “Developing and Maintaining Client Trust & Commitment in a Rapidly Changing Environment.” White Paper. www.financialplanningassociation.org/learning/research/client-communication.

Archuleta, Kristy L., Sarah D. Asebedo, D. B. Durband, S. Fife, M. R. Ford, B. T. Gray, M. R. Lurtz, M. McCoy, J. C. Pickens, and G. Sheridan. 2021. “Facilitating Virtual Client Meetings for Money Conversations: A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Skills and Strategies for Financial Planners.” Journal of Financial Planning 34 (4): 82–101.

Archuleta, Kristy L., Anita Dale, and Scott M. Spann. 2013. “College Students and Financial Distress: Exploring Debt, Financial Satisfaction, and Financial Anxiety.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 24 (2): 50–62.

Asberg, Kia. 2018. “Hostility/Anger as a Mediator Between College Students’ Emotion Regulation Abilities and Symptoms of Depression, Social Anxiety, and Generalized Anxiety.” In Emotions and Their Influence on Our Personal, Interpersonal and Social Experiences. Routledge: 178–199.

Cheng, Yuanshan, Chris Browning, and Philip Gibson. 2017. “The Value of Communication in the Client–Planner Relationship.” Journal of Financial Planning 30 (8): 36–44.

Eustis, Elizabeth H., Nicole Cardona, Maya Nauphal, Shannon Sauer-Zavala, Anthony J. Rosellini, Todd J. Farchione, and David H. Barlow. 2020. “Experiential Avoidance as a Mechanism of Change Across Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in a Sample of Participants with Heterogeneous Anxiety Disorders.” Cognitive Therapy and Research 44: 275–286.

Grable, John, Wookjae Heo, and Abed Rabbani. 2015. “Financial Anxiety, Physiological Arousal, and Planning Intention.” Journal of Financial Therapy 5 (2): 2.

Heo, Wookjae, Jae Min Lee, and Abed G. Rabbani. 2021. “Mediation Effect of Financial Education Between Financial Stress and Use of Financial Technology.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 42: 413–428.

Kenny, David A. 2015. “Measuring Model Fit.” Last modified September 12, 2022. https://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

Kitces, Michael, and Carl Richards. 2019. “Communicating with Clients to Bring Them Under the Cone of Trust.” Nerd’s Eye View. www.kitces.com/blog/client-communication-building-trust-kitce-and-carl/.

Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Publications.

Madianou, Mirca, and Daniel Miller. 2013. “Polymedia: Towards a New Theory of Digital Media in Interpersonal Communication.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (2): 169–187.

Maslowsky, Julie, Justin Jager, and Douglas Hemken. 2015. “Estimating and Interpreting Latent Variable Interactions: A Tutorial for Applying the Latent Moderated Structural Equations Method.” International Journal of Behavioral Development 39 (1): 87–96.

Muthén, Linda K., and Bengt Muthén. 2017. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. Muthén & Muthén. www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf.

Rosenberg, Rebecca. 2024. “How Can AI Help Financial Advisors?” Investopedia. www.investopedia.com/how-can-ai-help-financial-advisors-8385520.

Shapiro, Gilla K., and Brendan J. Burchell. 2012. “Measuring financial anxiety.” Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 5 (2): 92.

Sharpe, Deanna, Carol Anderson, Andrea White, Susan Galvan, and Martin Siesta. 2007. “Specific Elements of Communication that Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 18 (1): 2–17.

Spears, Britney. 2023. The Woman in Me. Simon and Schuster.

Tharp, Derek T. 2020. “Potential Consumer Harm Due to Regulation on Financial Advisory Communication in the FinTech Age.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 31 (1): 146–161.