Journal of Financial Planning: September 2022

Executive Summary

- A review was conducted for articles published between 2011 to 2021 in the Journal of Financial Planning (n = 257) to examine themes across theories, datasets, data analysis strategies, research methods, and implications for researchers and practitioners.

- The Journal research relied heavily on secondary data, most of which came from historical returns, and hypothetical data from simulations (n = 127).

- Contributors relied heavily on regression analysis and simulations to perform data analysis. A considerable number (n = 155) of articles did not use any statistical approach (e.g., theoretical papers or hypothetical case studies). Qualitative research was absent.

- The most prolific authors included David M. Blanchett, Wade D. Pfau, and Michael S. Finke. Significant contributors to the Journal included financial planning firms, Kansas State University, Texas Tech University, Morningstar, and The American College of Financial Services.

- Frequently cited article topics included money scripts, retirement planning, and Bitcoin, with the article “The Value of Bitcoin in Enhancing the Efficiency of an Investor’s Portfolio” being cited nearly twice as much as subsequent Journal research.

- Only 38 articles applied overt theoretical frameworks to ground their research.

- Approximately one-third of the articles (n = 90) had a practice implication header, but fewer had a research implication header (n = 13).

- Findings identified prominent financial planning topics in the last decade and bring attention to those that would benefit from increased attention with hopes to encourage future research and practice.

Jason Anderson, CFP®, CPA, is a lecturer in the B.B.A. program at the University of Kansas, owner of Gradmetrics, and a Ph.D. student studying personal financial planning at Kansas State University. Jason is interested in fintech, rural financial planning, and student loan planning. He can be reached HERE.

Joanne C. Wu, CFP®, PFP, is an international Ph.D. student in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University, and a senior financial planner at MD Management, a firm dedicated to the financial planning needs of Canadian physicians and their families. She can be reached HERE.

Ashlyn Rollins-Koons is an investment professional practicing in California and a doctoral student in Kansas State University’s personal financial planning program. Ashlyn’s research interests are in behavioral finance, religion and finance, natural disaster financial planning, and family financial socialization. She can be reached HERE.

Stephen Azaloff is the chief financial officer of Medical Manufacturing and a personal financial planning doctoral student at Kansas State University. Stephen is interested in research pertaining to entrepreneurs and their families, particularly entrepreneurial bootstrapping and financial behaviors that predict credit worthiness. He can be reached HERE.

Ruth McCaleb is an undergraduate student in the personal financial planning program at Kansas State University. She can be reached HERE.

Cheryl Rauh is the program manager of TRIO McNair Scholars Program and a personal financial planning doctoral student at Kansas State University. Cheryl’s research interests are in financial literacy and education, college student financial wellness, and financial communication. She can be reached HERE.

Megan McCoy, Ph.D., LMFT, AFC, CFT-I, is an assistant professor and director of the personal financial planning master’s program at Kansas State University. She serves on the board of directors for the Financial Therapy Association. She is also the associate editor of profiles and book reviews for the Journal of Financial Therapy.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions

View article in the DIGITAL EDITION

The Journal of Financial Planning (the Journal) is the Financial Planning Association’s (FPA) hub for educational content and knowledge that was developed to directly benefit financial planning firms and industry professionals. For more than 40 years, professionals, researchers, and subject matter experts have published original, thought-provoking content on all aspects of financial planning. This article explores the last decade of published research in the Journal to identify current research trends and future opportunities. Despite the Journal’s premier status in the field, an analysis of this nature for the Journal of Financial Planning has not yet occurred.

Identifying scholarly trends in decade reviews allows for a comprehensive description of research trends and future opportunities for research and practice. In fact, comparable articles have surveyed other financial planning journals such as the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning (Xiao et al. 2020), Financial Services Review (Hanna et al. 2011), and the Journal of Family and Economic Issues (Dolan 2020). Xiao et al. (2020) explained that these reviews provide an opportunity to explore how a journal can bolster its standing as a major outlet in financial planning practice and research. Hanna et al. (2011) described how the review process provides insights into patterns of research. Dolan (2020) raised the questions: “What do we still need to learn? Are the data sources we have been using adequate for what we need to know? Where should we focus our attention?” (591). These previous reviews of financial journals provided the motivation and backdrop for the current analysis.

The current review of the Journal analyzed the past decade of publications (2011–2021), a period marked by notable events such as the longest bull market in history, the onset of COVID-19, the emergence of cryptocurrency and other forms of digital currency, a shift to virtual client–adviser engagements, and the rise of do-it-yourself financial planning and investing. Researchers and practitioners had ample topics to discuss. As a developing academic discipline, the study of financial planning stands to gain from analyzing research trends. Toward that aim, this review explores the Journal’s common keywords in practice and research articles, top authors and their affiliations, most-cited articles, recurring theories, popular datasets, preferred analysis strategies, and research and practice implications.

Methodology

Content published in the Journal varies from monthly feature articles, interviews, columns, and peer-reviewed technical contributions with the intent to directly benefit financial planners in their work (Publons n.d.). Authors include scholars, practitioners, and content experts who contribute articles covering a broad range of financial planning topics. A special section in the Journal, the Next Generation Planner, caters to new financial planning industry professionals. According to the Journal’s editorial review submission guidelines, “Submission Guidelines for Articles,” readers are primarily FPA practitioners as opposed to researchers (Financial Planning Association n.d). There are approximately three practitioner articles for every research article in the Journal.

An initial export of articles in the Journal was completed in October 2021 from ProQuest One Academic (ProQuest). This export resulted in 2,338 total records and included articles, credits, table of contents, and stat banks. The authors verified the initial export for errors and omissions during the categorization process. In four instances, multiple records from the ProQuest export represented a single, multipart article. To rectify this, records were manually screened and categorized under the table of contents heading to provide broader coverage. After the manual review, eight articles were manually added from information found in the Journal’s issue. Then two additional levels of analysis were completed to examine the textual patterns in the full list of articles (n = 2,346).

First Level of Analysis: Examining Textual Patterns in the Journal

The full list of items (n = 2,346) was manually recategorized into the headings found in the table of contents across the issues in our publication range. These headings include cover stories, columns, contributions (the term used for research articles for 2011–2019), research (used for articles in 2020 and 2021), practice management, roundtable, special report, focus, in-depth, next-generation planner, book excerpt, commentary, and the departments.1 The minor articles found under the heading “departments” were removed due to their brevity. Next, the “Best of” issues were removed from this study as they are reprints of articles from the year and thus were already included in their original issue. Finally, we removed online exclusives (see the November 2019 issue) due to their divergence from the normal print cycle. The edited list totaled 1,113 article abstracts of which n = 257 were research articles and n = 856 were practitioner articles. This level of analysis offers insight into the differences between the research and practitioner articles in the Journal.

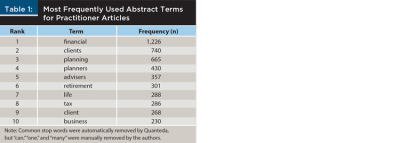

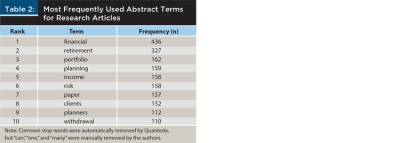

To identify the most frequently used words in the Journal, we used the Quanteda package in R. Quanteda is an open-source textual analysis tool for quantitative processing of language in documents (Benoit et al. 2018). This software package relies on artificial intelligence and natural language processing to scan text for patterns. Quanteda tabulated the most frequently used words in the ProQuest article abstracts for both practitioner and research articles. It is important to note that in the absence of Journal-provided abstracts, ProQuest (as well as other library databases) create their own versions and may diverge from the Journal’s and the authors’ intent. Regardless, these abstracts provided an opportunity to get an overarching perspective of the general focus of the articles. The resulting output is a list of the most frequently used words and their use count based on the ProQuest abstracts for both practitioner articles (Table 1) and research articles (Table 2).

A comparison of the most frequently used terms in the abstracts for practitioner articles and research articles showed key differences in the focus areas. While many of the terms used were common to both groups (financial, clients, planning, planners, and retirement), some were unique to each category. Unique terms for practitioners included advisers, life, tax, and business, and for academics included portfolio, income, risk, paper, and withdrawal. The term “clients” ranked much higher (second) in practitioner articles, compared to research articles (eighth). Also, “clients” ranked above “planning” and “planners” for practitioner articles, whereas it was ranked much lower than “planning” for academics. However, the combined frequency of “planning” and “planners” (1,095) exceeded the use of “client” and “clients” for practitioner articles (1,008).

The top 10 most frequently used words for both practitioner and research articles were then compared to key topics for CFP® certification. The CFP Board’s CFP® Certification 2021 Principal Knowledge Topics included professional conduct and regulation, general principles of financial planning, risk management and insurance planning, investment planning, tax planning, retirement savings and income planning, estate planning, and psychology of financial planning (CFP Board 2021). These topics are frequently updated by the CFP Board to align with the needs of the financial planning profession. Topic areas that are deemed important to the CFP Board but that were infrequent in the analysis of terms include “estate” and “psychology.” It is unclear if the CFP Board uses the term “risk management” and “insurance planning” interchangeably, but neither “insurance” nor “risk” are terms that frequently appear in practitioner articles. The term “risk” does frequently appear in research articles, ranking sixth, though it is important to note that our analysis in Quanteda does not reveal context; it is unknown if the high frequency of “risk” is related to insurance management, risk tolerance, or investments. Ambiguity also exists with the term “psychology,” which is not commonly used in the financial planning psychology realm, compared to other more common word choices such as anxiety, communication skills, conflict resolution, etc. Results may indicate that practitioner articles focused more on the knowledge topics of general financial planning, tax planning, and retirement planning, while academic articles focused on general financial planning, risk management and insurance planning, and retirement planning. The divergence in topic areas has implications for practitioners and researchers as it hints at the need for consuming both practice and research articles to fully be up to date on CFP Board topic areas. In addition, results may encourage special issues on topics that are not as large of a focus in either the practice or research domains.

Second Level of Analysis: A Deeper Look at Research Articles

The second level of analysis focused on peer-reviewed research articles (n = 257). These articles were reviewed using a double-blind process, in which neither the authors nor the reviewers are aware of the other. The goal is twofold; first to ensure the reviewers are both content and methodology experts beyond the scope of the Journal’s editor. Second, to ensure academic integrity and rigor by allowing the reviewer to remain unbiased regardless of the author’s status, and to be forthcoming with criticism. Individual authors were assigned to manually read each research article to identify top authors and affiliations, articles cited in other works, theoretical frameworks, datasets, data analysis methods, and implications for practitioners or researchers.

Authorship and Affiliation

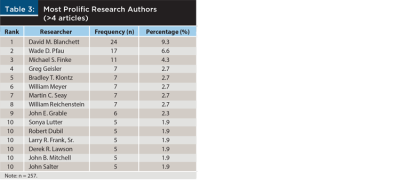

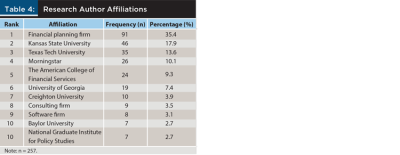

This review was inspired by previously completed journal reviews (e.g., Xiao et al. 2020; Hanna et al. 2011; Dolan 2020; Cummings and Heck 2015). We began our review in a similar fashion to the preceding reviews with a look into the most frequently published authors in the Journal. The findings summarized in Tables 3 and 4 show the rankings of the most prolific authors and affiliations across research articles. In addition to the tabulated results, two other dimensions are worth noting. First, a single female made the top 10 list (Sonya Lutter) and second, the great majority of authors appear to be white. Top affiliations are largely domestic (United States) versus international. Notably, Bradley T. Klontz is a mental health professional rather than a financial planner, but that may reflect the psychology of financial planning CFP® Certification Principal Knowledge Topic that did not show up in our analysis of terms through Quanteda.

The review of affiliations uncovered that many of the research articles were written by practitioners (Table 4). Researchers were affiliated with their institution, normally a university or research institute. Articles that were written by practitioners were categorized by either a financial planning firm affiliation or occupation (examples include financial planner, economist, insurance professional, investment professional, tax professional, consulting, and retired). A few (n = 5) were categorized as “other” because there was no suitable category (e.g., firms specializing in non-financial planning industries). Each author was given one primary affiliation, as some authors listed multiple affiliations. Many articles in this analysis had multiple authors. The top affiliation category is financial planning firms followed by Kansas State University, Texas Tech University, Morningstar, and The American College of Financial Services. The results highlight one of the unique strengths of the Journal: the ability to persuade non-academics to submit research articles to the Journal.

Article Citations

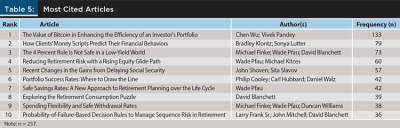

Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) is a web search engine for scholarly work (e.g., articles, conference proceedings, reports). A unique aspect of Google Scholar is that it provides a “cited by” number, which is the number of times the article has been cited within other articles. Table 5 provides the results of the most cited research articles in the Journal. The most frequent author appearances on this list include Chen Wu and Vivek Pandey (cited 133 times); followed by Bradley Klontz and Sonya Lutter (cited 79 times); Michael Finke, Wade Pfau, and David Blanchett (cited 73 times); Wade Pfau and Michael Kitces (cited 60 times); and John Shoven and Sita Slavov (cited 57 times). Popular cited topics included retirement planning, Bitcoin, and money scripts. This could be reflective of emerging research that has not yet been covered by other financial planning journals, among other reasons.

Theories

Theory is a systematic collection of concepts and relations that connect ideas and data (White and Klein 2002). Theory is important because it provides a lens to observe different phenomena. When we examine an object, a situation, a trend, or a phenomenon through one lens, it may appear different from if we had looked at it through another theoretical lens (Bengtson et al. 2005). Buie and Yeske (2011) lamented that financial planning remains in search of an underlying theory and emphasized the importance of engaging in the scientific process. The financial planning field has often borrowed theories from other fields and only recently have efforts been made to adopt theories on a wider basis (Overton 2008). The frequency of theory used in the Journal is summarized in Table 6.

Overall, mean-variance portfolio theory was the most frequently used theoretical framework, though it framed only five articles out of the 257 contributions. Some authors used alternate terms for this theory, including modern portfolio theory and portfolio theory. The life cycle hypothesis also underpinned many articles, even when not explicitly defined as a theoretical framework. In total, only 38 articles included theoretical frameworks, and 35 total theories were applied. Seven articles applied more than one theory to establish their theoretical framework. Ultimately, only 14.8 percent of research articles in the Journal applied theory, indicating significant room for growth in the application of theory.

Datasets

Datasets are the aggregate responses based on surveys, interviews, focus groups, or observations of a group of participants. Primary data is information collected directly by the researcher, whereas secondary data is accessed through datasets collected from other researchers (Andrews, Higgins, Andrews, and Lalor 2012). Researchers commonly use secondary data as it is less costly and time-consuming to gather results from large samples compared to collecting primary data (Johnston 2014). Secondary data can also be helpful to researchers who desire to study populations that are not easily accessible or topics that respondents may feel uncomfortable discussing (Andrews, Higgins, Andrews, and Lalor 2012). Despite the benefits, there are disadvantages inherent in secondary analysis, and the use of secondary data has its limitations. According to Babbie (2015), the key problem involves the recurrent question of validity. Datasets typically are created with a distinct purpose, which may differ from that of the researchers, and authors may be unable to study certain variables. In addition, there is a time factor with secondary data as, often, time has passed between the data collection by the primary data collectors and when the dataset is used in secondary data studies.

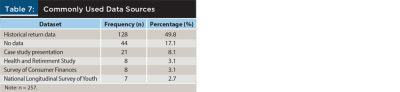

Table 7 summarizes the most-used data sources in the Journal publications in the last decade. Publications have primarily relied on secondary data developed through historical returns. Of the 257 research articles analyzed, 49.8 percent used historical return data. These articles may be especially useful to practitioners, who use historical returns in their day-to-day practice. However, historical data is limited in its ability to describe future market performance. The most prominent secondary datasets used by researchers were the Health and Retirement Study (3.1 percent), the Survey of Consumer Finances (3.1 percent), and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (2.7 percent).

The results of this analysis indicate that datasets are not commonly used in the Journal. A notable number of articles (17.1 percent) did not use data at all but instead were theoretical, discussing topics such as industry trends, compliance topics, or client service. The next most-used category of “data” was case studies (8.1 percent). Although case studies provide tangible demonstrations of how to apply skills learned in practice, the results need to be tested to ensure their validity.

Primary data collection remained rare in the Journal during the years considered. Our analysis uncovered only 18 studies that used primary data, which averaged out to less than two primary data-driven articles a year. The Journal has reduced its total number of research articles throughout the last decade. There were 27 research articles in 2011 and only 12 in 2020. The reduction in the number of research articles may have been partially due to an increase in quality as demonstrated by an increase in data-driven articles. For example, in 2012, the use of data amongst research articles was less than 80 percent of publications. The years in which data use was at its highest were 2016 and 2020. Secondary and primary data have their unique advantages and disadvantages, but researchers should continue finding ways to rely on primary data and use less commonly accessed secondary datasets. Researchers might also consider looking outside the box at datasets from other client-centered fields (i.e., mental health or medical datasets) to find ways to better serve clients.

Data Analysis Strategies

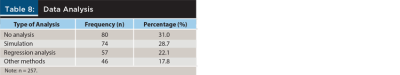

The 257 articles classified as research were examined for their data analysis strategy. Each article was assigned one of four summary categories according to the following logic (see Table 8). First, articles that relied on a simulation approach, most commonly Monte Carlo, were labeled “simulation.” This was the most utilized statistical data analysis method in the reviewed period, making up 41.81 percent of the statistical data analysis strategies used. Next, if an article showed evidence of regression and/or correlation analysis among variables, it was categorized as “regression analysis.” Sample methods include ordinary least squares (OLS), Poisson regression, and probit/logit models. Nearly one-fourth of the 257 articles examined made up this category, ranking it as the second most-used statistical method and the third most-used method overall. Finally, articles that used a statistical data method that neither fit into “simulation” nor “regression analysis” were considered “other,” of which the most frequently used statistical tests in this category were differences in means, such as t-tests and chi-square analysis. Several articles used basic descriptive statistics to convey the researched topic. By using more advanced statistical methods, authors might be able to derive further insights and move from the descriptive to the inferential. Furthermore, they aid in developing actionable implications and ease of pursuing further research on the given topic.

The most notable finding from the study is the observation that 81 of the 257 examined research articles did not use any method at all, and instead were hypothetical case studies, theoretical papers, or situational interpretations. Common examples of situational interpretations were articles dedicated to various tax issues, where the situational interpretation of the issue was valuable and did not require primary or secondary data or a specific empirical method. No studies used qualitative research, which presents an area of uncharted opportunity for the Journal. Qualitative research has distinctive strengths effective for studying subtle nuances in attitudes and behaviors and for examining social processes over time (Babbie 2015). More qualitative research in financial planning will provide a broader understanding of both client and planner’s lived experiences.

Practice and Research Implications

In numerous disciplines, a gap exists between research and practice (Owenz and Hall 2011; Tkachenko, Hahn, and Peterson 2017; Walker, Chandra, Zhang, and van Witteloostuijn 2019). Often, the discussion about the gap between research and practice focuses on the limitations of the “other.” Researchers argue that practitioners do not consume their findings, and practitioners protest that researchers do not publish work worth consuming (e.g., researchers focus on college students rather than financial planning clients or the writing is too difficult to understand). As a result, some practices shown to be effective by scientific research are seldom used in applied settings, and some commonly implemented practices are not empirically validated, may be ineffective, or even be harmful to clients (Kazdin 2008).

Klontz (2016) authored a paper about how little financial planning research appears to matter to practitioners, citing a conference he attended that discussed this research–practice gap. “For the most part, financial planning research does not matter to financial planners. It is too obscure. It is too difficult to digest and even when digested, it is too unrelated to what concerns them most. For the most part, it does not inform financial planning practice” (43). Klontz highlights the Journal’s essential role in bridging the gap, stating that it is one of the few academic journals in any discipline that attempts to make the research articles included directly relevant to practitioners. Our study sought to explore how well the Journal bridged the gap through an examination of overt practice and research implications.

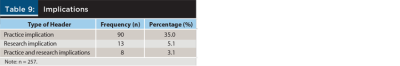

First, we explored how well the research spoke to practical implications by examining the 257 research articles, noting the frequency of clear and explicitly labeled practice implication headers in the research article (see Table 9). Findings showed that 90 of the 257 articles had a header. Each of the 257 articles were read to determine if clear implications for practitioners or researchers were present, regardless of the header description. It was deemed that 257 of 257 articles clearly stated practical implications for practitioners. Research implication presence was significantly less. Only 13 of the 257 articles included an explicit research implication header but an additional 68 included clearly stated research implications elsewhere in the paper.

Second, efforts were made to identify whether practice management articles had implications. ProQuest was used to search the Journal (with the query pubid(4849) AND implication* within “Anywhere”) to identify practice articles that identified implications (n = 151). Next, research articles were eliminated, leaving a sample of 59 practice articles that had the word “implication” anywhere in the article. Errors were recorded in the validity verification of the articles, as after reading them it was discovered that several did not include the word implication despite the search attempt. This might be due to varying optical character recognition (OCR) functionality between full-text PDFs within ProQuest. The Journal may want to reach out to larger databases like ProQuest and encourage them to make accessible PDFs for the articles available. The descriptions of these 59 articles are shared here with the caveat that a more in-depth examination of the complete set of practice management articles is required before making final conclusions. Only seven of the 59 practice-based articles included an explicit practice implication header, and none included a research implication header. Then each article was read for any mention of research and/or practice implications. While 59 of 59 articles were deemed to have included implications for practice, none of the practice management articles were deemed to have a presence for research implications. With more explicit research and practice implications sections (preferably with clear headers) for both practice and research articles, the Journal can improve its already profound efforts to publish works useful to both practitioners and researchers.

Limitations

This study had three main limitations. First, a full year of articles from 2021 is not used as at the time of export, the author’s ProQuest database had an embargo on the most recent Journal articles. Articles pulled for this study from ProQuest terminated with the April 2021 issue. Second, filtering by the main headings found in the Journal table of contents gave focus to the comparison of practitioner and researcher interests. Although it was useful to filter out superfluous records in the original export file from ProQuest, it is possible that the process limited the overall validity of the results. Minor category articles that were excluded could have provided other relevant topics, particularly ones pertinent to practitioners. Finally, the abstracts used for textual analysis were not provided by the Journal directly: they were created by—and specific to—the ProQuest database. A search uncovered different abstract constructions across databases (e.g., Business Source Premier from EBSCO had different abstracts). The textual analysis findings provided by this study should be interpreted within this context.

Conclusion

This examination of the last decade of published works from the Journal of Financial Planning has revealed several key discoveries, especially regarding research contributions. One of the unique strengths of the Journal is its role as a meeting ground for the ideas of practitioners and scholars in a single publication. The bulk of the Journal’s output is by practitioners for fellow practitioners, and there are gaps in the overlap between the topics of interest demonstrated by practitioners versus those explored by researchers. The Journal is an excellent source of practical information for financial planners, but more can be done to uphold former Journal editor Lance Ritchlin’s vision to “bridge the gap between what practitioners know and the skills they need to acquire if financial planning is to be a true profession” (Ritchlin 2011, 10). The Journal might foster more research engagement by ensuring full-text articles are searchable with OCR, incorporating abstracts in library databases, or creating standardized classification codes (similar to JEL created by the American Economic Association). These changes increase opportunities for researchers to find and therefore cite work from the Journal and could promote interest in producing research targeted for the journal. Greater research engagement brings more willing reviewers to promote rigorous expectations for framing research, in theory, applying complex statistical analysis, and introducing novel datasets. A more robust research offering could go a long way in strengthening the Journal’s standing in the field of personal financial planning and enhance opportunities for research to connect with the interests of practitioners.

Citation

Anderson, Jason, Joanne C. Wu, Ashlyn Rollins-Koons, Stephen Azaloff, Ruth McCaleb, Cheryl Rauh, and Megan McCoy. 2022. “A Decade of Research in the Journal of Financial Planning (2011–2021).” Journal of Financial Planning 35 (9): 70–81.

Endnote

- Note that although peer-reviewed research articles were referred to as both contribution and research articles in the Journal, we will refer to them solely as research articles moving forward.

References

Andrews, Lorraine, Andrea Higgins, Michael Waring Andrews, and Joan G. Lalor. 2012. “Classic Grounded Theory to Analyse Secondary Data: Reality and Reflections.” The Grounded Theory Review 11 (1): 12–26. http://groundedtheoryreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/ClassicGroundedTheorytoAnalyseSecondaryDataVol111.pdf.

Babbie, Earl. 2015. The Practice of Social Research. 14th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Bengtson, Vern L., Alan C. Acock, Katherine R. Allen, Peggye Dilworth-Anderson, and David M. Klein. 2005. “Theory and Theorizing in Family Research: Puzzle Building and Puzzle Solving.” In Sourcebook of Family Theory and Research: 3–33. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Benoit, Kenneth, Kohei Watanabe, Haiyan Wang, Paul Nulty, Adam Obeng, Stefan Müller, and Akitaka Matsuo. 2018. “Quanteda: An R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data.” Journal of Open Source Software 3 (30): 774. doi: 10.21105/joss.00774.

Buie, Elissa, and Dave Yeske. 2011. “Evidence-based Financial Planning: To Learn . . . like a CFP.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (11): 38–40, 42–43.

CFP Board. 2021, March. “CFP® Certification 2021 Principal Knowledge Topics.” www.cfp.net/-/media/files/cfp-board/cfp-certification/2021-practice-analysis/2021-principal-knowledge-topics.pdf.

Cummings, Benjamin F., and Jean L. Heck. 2015. “The Most Prolific Authors in Financial Planning Literature.” Journal of Financial Planning 28 (12): 50–62.

Dolan, Elizabeth M. 2020. “Ten Years of Research in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues: Thoughts on Future Directions.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 41 (4): 591–614. doi: 10.1007/s10834-020-09739-z.

Financial Planning Association. n.d. “Submission Guidelines for Articles: Editorial Review.” Accessed April 26, 2022. www.financialplanningassociation.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Editorial%20Review_UPDATED%20060921.pdf.

Hanna, Sherman D., HoJun Ji, Jonghee Lee, Jiyeon Son, Jodi Letkiewicz, HanNa Lim, and Lishu Zhang. 2011. “Content Analysis of Financial Services Review.” Financial Services Review 20 (3): 237–251.

Johnston, Melissa P. 2014. “Secondary Data Analysis: A Method of Which the Time Has Come.” Qualitative Quantitative Methods in Libraries 3 (3): 619–626.

Kazdin, Alan E. 2008. “Evidence-Based Treatment and Practice: New Opportunities to Bridge Clinical Research and Practice, Enhance the Knowledge Base, and Improve Patient Care.” American Psychologist 63 (3): 146–154.

Klontz, Bradley T. 2016. “Why Financial Planning Research Doesn’t Matter (and What to do About it).” Journal of Financial Planning 29 (10): 42–44.

Overton, Rosilyn H. 2008. “Theories of the Financial Planning Profession.” Journal of Personal Finance 7 (1): 13–41.

Owenz, Meghan, and Susan R. Hall. 2011. “Bridging the Research–Practice Gap in Psychotherapy Training: Qualitative Analysis of Master’s Students’ Experiences in a Student-led Research and Practice Team.” North American Journal of Psychology 13 (1): 21–35.

Publons. n.d. “Journal of Financial Planning”. https://publons.com/journal/59998/journal-of-financial-planning/.

Ritchlin, R. 2011. “Growing Pains.” Journal of Financial Planning 24 (11): 10.

Tkachenko, Oleksandr, Huh-Jung Hahn, and Shari L. Peterson. 2017. “Research–Practice Gap in Applied Fields: An Integrative Literature Review.” Human Resource Development Review 16 (3): 235–262.

Walker, Richard M., Yanto Chandra, Jiasheng Zhang, and Arjen van Witteloostuijn. 2019. “Topic Modeling the Research–Practice Gap in Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 79 (6): 931–937.

White, James M., and David M. Klein. 2002. Family Theories. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Xiao, Jing Jian, Beatrix Lavigueur, Amanda Izenstark, Sherman Hanna, and Francis C. Lawrence. 2020. “Three Decades of the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 31 (1): 5–13. doi: 10.1891/JFCP-20-00010.