Journal of Financial Planning: June 2012

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CPA, CFP®, is a professor of tax and financial planning at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. He is also co-author (with Julie Welch) of 101 Tax Saving Ideas and co-editor (with Leslie Daff) of WealthCounsel® Estate Planning Strategies. (gardnerjr@umkc.edu)

Leslie Daff, J.D., is a State Bar Certified Specialist in estate planning, probate, and trust law and the founder of Estate Plan Inc. in Orange County, California, and Overland Park, Kansas. (ldaff@estateplaninc.com)

Julie Welch, CPA, CFP®, is the director of tax and a shareholder with Meara Welch Brown PC in Kansas City, Missouri. (julie@meara.com)

As medical advances extend human life expectancy, the likelihood that an individual will become incapacitated before dying increases. For our clients’ wealth planning and conservation purposes, it is important that we recognize when a client is incapacitated and thus unable to execute estate planning documents or manage his or her affairs.

The modern estate plan includes a: revocable living trust, pour-over will, durable power of attorney for financial matters, durable power of attorney for health care, living will, assignment of personal property to the trust, deed(s) of real estate to the trust, and certification of trust. The client must have capacity (a “sound mind”) to execute these legal documents. Otherwise, the validity of the documents could be questioned by heirs and the courts.

In deciding whether an individual was able to execute a will, one court wrote: “... old age, feebleness, forgetfulness, filthy personal habits, personal eccentricities, failure to recognize old friends or relatives, physical disability, absentmindedness, and mental confusion do not furnish grounds for holding that a testator lacked mental capacity” (Estate of Selb (CA Appellate Court 1948)). The California Probate Code states that “a person with sufficient mental capacity is able to:

- Understand the nature of the act he or she is doing

- Understand and recollect the nature and situation of his or her property, and

- Remember, and understand his or her relations to, the persons who have claims upon his or her bounty and whose interests are affected by the provisions of the instrument.”

This traditional language sets a very low standard.

A higher standard, the capacity to enter a contract, is generally required to execute a revocable living trust. According to California’s Due Process in Competence Determinations Act (1995): “A person lacks the capacity to make a decision unless the person has the ability to communicate verbally, or by any other means, the decision, and to understand and appreciate, to the extent relevant, all of the following:

- The rights, duties, and responsibilities created by, or affected by, the decision

- The probable consequences for the decision maker and, where appropriate, the persons affected by the decision

- The significant risks, benefits, and reasonable alternatives involved in the decision.”

This standard describes much higher cognitive function than needed to sign a will. In Andersen v. Hunt (CA Appeals Court 2011), the court held that while most provisions of a trust require the higher contractual capacity standard, the property transfer provisions of a trust are valid if the client evidenced the lower capacity standard of a will. However, courts in other states may hold differently. Arguably, because of the interrelationship of the documents executed as part of an estate plan and because today’s wills “pour over” property into the revocable living trust for management, the higher standard could apply to all of these documents.

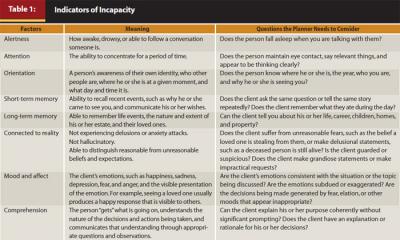

Indicators of incapacity are detailed in Table 1. The capacity to enter a contract typically requires the presence of all these factors, whereas the capacity to execute a will requires primarily long-term memory and a connection to reality.

Who Decides?

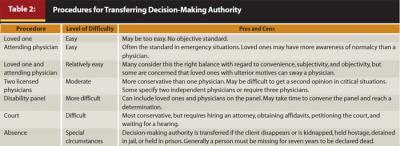

Three of the documents mentioned above—the revocable living trust, the durable power of attorney for financial matters, and the durable power of attorney for health care—transfer the client’s decision-making ability to others in the event of incapacity. What is the procedure for making this transfer of decision-making authority? Usually loved ones, physicians, or a combination of the two make the decision, but the estate planning documents may require a disability panel or court. There are pros and cons to each (see Table 2). It is important for the procedure for transferring this responsibility to be consistent between the documents because the client and family want an integrated continuation of the client’s financial management, medical care, and payment of expenses and debts.

Some individuals who want to remain in control as long as possible or who are concerned about others making decisions for them prefer a conservative standard, whereas others who have been in long-term relationships and are confident in their decision makers are comfortable with an easier process. The goal is to strike the right balance between objectivity, convenience, and timeliness.

Avoiding Living Probate

Similar to probate at death, a probate while the incapacitated person is alive can be costly and time-consuming and is most easily avoided with a revocable living trust. Surprisingly, one of the most common causes of “living probate” is assets titled as joint tenants with right of survivorship. This titling avoids probate when the person dies, but can require the involvement of a court if the person becomes incapacitated and needs to sell the property.

Family members are often in denial about the medical condition of their loved ones, meaning advisers may be the first to see the signs of incapacity. It is important that the adviser encourage the client to prepare an estate plan while the client still has capacity.