Journal of Financial Planning: June 2012

Paula H. Hogan, CFP®, CFA, an adviser in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has served on the national boards of FPA and NAPFA and has contributed several articles to the Journal of Financial Planning and AAII Journal.

Executive Summary

- This article describes the economic theory behind goals-based investing paired with a robust life planning process. The result is a paradigm shift in the definition and delivery of personal financial advice.

- Reliance on economic principles shifts the planner’s focus to the client’s lifetime standard of living, rather than wealth, and highlights the need to consider risk capacity separately from risk tolerance.

- A key part of the financial adviser’s role is to facilitate an ongoing and robust values clarification process with the client.

- The author disputes a popular belief that stocks are safe if held for a long time, and suggests the planning implications for risk management, investment product evaluation, and planning calculations.

- An updated definition for financial planning is proposed: the lifelong process of integrating personal values with the management of both human and financial capital for the betterment of self and community.

I’ve been using an updated model for financial planning with my clients as a result of talking with and learning from several economists with particular expertise in investment risk management, and with experts in the life planning arena. What has been most surprising and helpful to me is how the ideas from these disparate experts dovetail into a coherent point of view for delivering personal financial advice that is effective—and different from mainstream financial advisory practice. This article offers a summary of these ideas for the purpose of inviting further discussion.

The Intersection of Economic Theory and Life Planning

Economics offers a full body of knowledge about securing lifetime financial security for an individual that, oddly, is not incorporated into our financial planning body of knowledge. The theory, known as the Bodie Merton Samuelson theory of life-cycle saving and investing (LCSI), has been well settled in the economic literature since at least the 1970s. Interestingly, LCSI positions a person’s human capital as the central focus. Economists define human capital as the present value of lifetime earned income. As an adviser, I find it helpful to frame human capital as what you do in the world with your skills and talents and how society chooses to pay you for those endeavors.

LCSI further focuses on optimizing earned income, matching investment risk to goals, and optimizing spending over one’s lifetime. These are the core planning tasks in the LCSI theoretical model. These core tasks can also be seen as the economic expression of life planning, that is, the process that facilitates the discovery and achievement of one’s lifetime goals. Linking the LCSI economic model with a robust life planning process reveals our distinct contribution as advisers and opens the path for delivering personal financial advice that is supported by a coherent theoretical model.

Let’s look first at the two core tenets of LCSI to begin to see the possibility for an updated, unifying point of view for financial planning.

1. Everyone has both financial capital and human capital, but human capital is central. In the context of this first core tenet, unless there is a large inheritance, human capital will be the primary determinant of an individual’s lifetime standard of living. The planning implication is that the person is the focus of attention, not the portfolio, and that the financial capital is tailored to the human capital.

For example, if the human capital is highly correlated with the stock market or is otherwise uncertain, unstable, or limited, then the risk in the financial portfolio is commensurately and deliberately limited. As Moshe Milevsky asks, are you a stock or a bond? Understanding and planning around the character of human capital, and around its correlation with equity risk, is now a core investment strategy.

If human capital is the primary determinant of long-term financial well-being, then a corollary is that human capital also needs to be managed, cultivated, and protected. The imperative to cultivate and protect human capital leads, for example, to a more than cursory need for adequate life and disability insurance planning. It also calls for what Wisconsin-based adviser Mike Haubrich has coined “career asset management.” Haubrich makes a case for including career asset management in the standard six-step process for financial planning. From this perspective, having reserves not just for emergencies but also for possible future career changes makes sense, as does benchmarking a client’s pay in the workforce as a standard part of the annual review. It further introduces the appeal of advisers working collaboratively with career counselors in order to help a client chart the optimal course for human capital management.

The emphasis on human capital in the LCSI theory also positions life planning as central to the advisory mission. Life planning focuses on values clarification and goal specification and thus, like LCSI theory, puts the individual as the focus of attention. A seminal Journal of Financial Planning article (Anthes and Lee 2001) defines life planning as a deliberate process designed for:

- Helping people focus on the true values and motivations in their lives

- Determining the goals and objectives they have as they see their lives develop

- Using these values, motivations, goals, and objectives to guide the planning process and provide a framework for making choices and decisions in life that have financial and non-financial consequences

From the outside, life planning can look like counseling or therapy. Life planning, however, is distinct from the medical/therapeutic model. Life planning is a growth model, employing self-assessment and visioning to create a desired future, with the goal of moving the client’s well-being from functional to optimal. In contrast, the medical/therapeutic model emphasizes the diagnosis of a problem and healing or resolving something in the past in order to move the client’s well-being from dysfunctional to functional.

Many advisers shy away from life planning, deeming it to be outside of their role as financial adviser and beyond their comfort zone and/or skill set. In their business model, clients are asked to specify goals during the financial planning process, but values clarification, which comes before goal setting, is not a standard, intentional part of their process.

Advisers engaged in the life planning process believe that financial planning begins with values clarification and is anchored by a continual process of envisioning the desired future. George Kinder, a leader in the life planning movement, points out that financial planners “inevitably deal with the strong correlation between money and emotion, [and thus] need simple but effective skills for that aspect of their work.” Marty Martin, Psy.D., a specialist in the psychology of money, has commented that the relationship between financial advisers and their clients is often more intimate than the relationship between therapists and their patients. In this context, there would seem to be an imperative for advisers to develop listening and other life planning-type skills intentionally and with supervision, instead of naively on an ad hoc basis.

It is daunting to think about when, how, and why to incorporate life planning into one’s business model. I find that an analogy with tax planning offers some insight. In the early days of financial planning, it was possible to not include tax planning in routine financial planning and instead to deem it “something you do with your tax preparer.” However, these days there isn’t any part of the financial plan that is not at some point viewed by the adviser through the lens of tax planning. Although business models vary, for example, with respect to whether accountants are on staff and whether tax returns are done in-house or not, the competent adviser today is at least an informed generalist with respect to tax planning. Similarly, it may be possible today to practice with life planning deemed “something the client does with others,” but I believe we are shifting toward a new paradigm in which advisers must decide how their business model will incorporate adequate life planning services.

CFP Board apparently agrees. A close look at Practice Standard 200-1 reveals that as a routine part of the six-step planning process “the practitioner will need to explore the client’s values, attitudes, expectations, and time horizons as they affect the client’s goals, needs, and priorities.” As life planning expert Carol Anderson points out, life planning can be seen as the implementation of Practice Standard 200-1.

A sign of disruptive change in our industry is that CFP Board in essence requires in its Practice Standard 200-1 that life planning be a routine part of the planning process but does not yet include the LCSI point of view in its curriculum. In contrast, the CFA Institute is now incorporating LCSI in its readings, but the CFA Institute is not yet a resource for life planning as a core strategy for human capital management.

LSCI theory goes a step further with its second core tenet:

2. People care most about their lifetime standard of living, not portfolio wealth. To focus on income, not wealth, may seem like a small change. But a change in the goal necessarily changes what is done and not done to meet that goal. In particular, it requires a fresh look at success metrics, risk management strategies, and the products used.

Listening to ordinary conversation supports the validity of this core tenet. I find that just as Jane Austen describes Darcy as being a man of 10,000 pounds per year income, most clients also describe their retirement goals in terms of lifetime standard of living, not wealth. In my experience, if you ask a client an open-ended question about what the client wants in retirement, the answer will be some combination of these sentences:

- I want to step out of the workforce and be able to keep my same level of living.

- I am very concerned about health care costs.

- If things go well, I’d like to have some extra money to do things like travel or help our children.

- I don’t want to go backward in my level of living.

- I am very concerned about financial safety. I don’t want to run out of money. I just want to be safe.

Note that these comments are all about income, downside protection, enjoying upside if upside happens, and not going backward. This is precisely what the LCSI theory predicts. This second core tenet shifts the focus of attention definitively toward risk management, and in particular toward managing the risks of longevity and inflation, and finding downside protection.

It also highlights the need to smooth consumption. Consumption smoothing is a term from economics. In LCSI a key planning goal is to move income from times of high income to times of low income (working years to retirement years) and from good times (such as when you are healthy) to bad times (such as when you are sick or disabled or need custodial care). Some tools for smoothing income include savings, debt, and insurance. A central challenge of managing finances for an individual is smoothing consumption—pushing cash flow around to the right time and circumstance, because awkwardly, income and expenses don’t flow in the same rhythm.

“Floor” is another term from the LCSI theoretical model. It indicates the client’s base standard of living—the barebones level of living below which the client does not want to go. In the LCSI framework, until you have secured the floor, risk capacity is the main focus. Then, to the extent that there is remaining wealth, it is reasonable to focus more on risk tolerance. Needs get covered with safe assets, while wants can be funded with the more volatile assets to the extent that a higher risk profile matches the client’s informed personal preference. Note: this line of reasoning also leads to updating one’s conceptual definition of the “safe asset” from U. S. Treasury bills to an immediate lifetime annuity that goes up with inflation but never down.

The planning implication is that there is rich possibility for improving the client’s financial security and personal happiness by helping to ensure that earned income is right for the client and that spending, on both needs and wants, also fits the client’s preferences and circumstances. This conclusion is supported by LCSI economic theory, CFP Board Practice Standard 200-1, and life planning principles.

Integrating Theory with Best Practices

What the economists don’t know: Implementing the LCSI point of view day-to-day is an intriguing challenge. Economists tend to assume that clients come into a planner’s office already knowing where their cash is being spent and able to specify concrete financial goals and the likely path of their earned income, and (icing on the cake) also to specify which expenses are lifetime needs and which are lifetime wants. In the trenches, it is clear that none of these assumptions are true.

The planning implication for the adviser is to provide the bridge between excellent theory and day-to-day reality by facilitating an ongoing and robust values clarification process as the foundation for the specification of concrete financial goals. In the trenches it also becomes clear that value decisions play out in the day-to-day cash management decisions, and thus there is a commensurate need for better ways to get meaningful cash management choices in front of clients as well. Finding ways to tune up the client’s ability to envision the specifics of the base versus desired lifetime standard of living is also an ongoing, fundamentally important process. In other words, life planning, as a core strategy for human capital management, can help by facilitating the process in which a client discovers and implements the optimal level of earning, saving, investment risk-taking, and spending.

What economists wish we knew: Economists view our traditional approach to financial planning as flawed by the hidden fallacy that stocks are safe if you have a long time horizon and thus may be relied upon even when funding critical personal goals. Unfortunately, this statement is a mangled version of a very exact and correct principle: stocks are appropriate if you have enough resiliency to compensate for losses in your financial capital. It is not time that gives you financial resiliency, it is the ability and willingness to go out and earn more money, or to cope with having less. Incorporating this understanding into daily work with clients changes the advice they are offered. Here’s how economists see this issue:

Time does not soften the risk of stocks. Our culture has transformed the correct statement regarding resiliency into a false belief that a long holding period somehow softens the risk of owning stocks. This is not true, and yet it is embedded in our software programs, our thinking, and even in consumer education literature from both the government and major financial firms. It is true that the average return of stocks is positive over time, but shortfall risk—the risk that you won’t have the desired amount of money at a particular time—increases with time.

To make an analogy with weather, think of the “cone of uncertainty” for hurricanes. The farther out in time, the wider the geographic area where the hurricane could land and do damage. Similarly, with stocks, the longer the time period, the wider the range of possible portfolio ending values. This makes sense. Stocks offer a higher expected return exactly because they also carry a higher risk than other investments. To confirm your understanding, try buying shortfall insurance from Wall Street, where you will find that the premium increases with time.

College funding is a classic example of this core misunderstanding. It is not uncommon that someone with a 4-year-old and a 14-year-old would be advised to have a higher stock exposure for the 4-year-old because “that child has a longer time horizon.” However, unless your client has an alternative means of paying tuition, he or she needs a certain amount of actual cash in the college savings fund the day tuition is due. To purchase protection from Wall Street against the risk of falling short of that specified amount is more costly for the 4-year-old than for the 14-year-old.

This does not mean that stocks are bad, but it does clarify that stocks are risky, no matter how long the time horizon. It further points out that risk management is goal-dependent, and not simply an exercise in discerning risk tolerance. Someone can have high risk tolerance but be low on risk-bearing capacity.

Economists would ask us: if we offer a financial plan to a client that requires favorable stock performance to succeed, is it a plan or a hope? They propose instead an emerging best practice of generating base projections that show what the planning result is expected to be with no volatility risk, and in particular illustrating the extent to which the lifetime base standard of living is covered with lifetime inflation-protected income.

Implications for Financial Planning: Full Paradigm Shift

If life planning breathes some life into the implementation of economic theory, and if an updated economic view for arranging lifetime financial security for the individual is adopted, then how we think about risk management, planning calculations, investment product evaluation, and the adviser value proposition also changes. An industry-wide paradigm shift becomes visible, and daily advisory practice is reinvented.

Risk Management. Before the Markowitz mean-variance paradigm, risk was assigned. Widows and orphans got the stable investments, and executives got the more volatile assets. With the Markowitz paradigm, risk management shifted toward diversification, and now, post-Markowitz, risk is increasingly sliced and diced and traded to the right party. The economists say that markets are becoming more complete. The possibilities for actually implementing LCSI, which implies goals-based investing with specific risk allocation, are thus becoming commensurately more numerous.

How did this happen? Look to the derivatives market. As background, option theory was first figured out in the 1970s. The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) started in 1973, and by 1975 traders were trading options on the exchange. This is the fastest transformation of theory to practice in the history of finance. Like it or not, and whatever your expertise in or opinion about derivatives or their regulation, the derivatives market now dwarfs the traditional stock/bond markets and is here to stay.

The good news is the potential, as derivative strategies come into the retail market, of designing products that are more closely tailored to the client’s needs and preferences—to slice and dice risk and then get it to the correct party. Despite all the controversy and uncertainty about the derivatives markets, structured products are a big potential plus for our clients once we get the product design and distribution channels worked out fairly. In essence, we’re shifting out of just diversifying risk to a more sophisticated process of helping the client figure out which risks to keep and which to dilute with sharing or trading.

Investment Product Evaluation. Analogously, how we evaluate products also shifts as the goal of planning is updated and more product solutions become available. In previous times, when considering a new investment, we would ask whether it would appreciate. Then, we learned to ask what it would do for diversification. We are now asking: is it floor or upside, and with what risk parameters?

Planning Calculations. The goals-based investing philosophy of LCSI requires that each goal be assigned a distinct investment allocation based on risk capacity, not just risk tolerance, and further that these allocations reflect the reality that optimal allocations tend to become more conservative over time. In contrast, it is not unusual for traditional planning software to assign one global portfolio allocation that is the same across all goals, fixed in time, and based mainly on assessed risk tolerance, not capacity. In addition to the possibility of specifying risk inappropriately, the net effect of the traditional approach can be to assume larger returns for a longer period than is reasonable, and thus to underestimate the required saving today. Goal-based investing requires updated software modeling.

Value Proposition. The adviser’s value proposition also morphs as the financial industry develops. In the old days, we said we’d pick the right products. Then, we said we’d pick the right products and use diversification to help the client build a large nest egg. But now the value proposition is very different: we’ll work together to optimize your human capital, and then as your adviser I will take the lead to specify how you can safely smooth consumption over time. In other words, human capital comes first, with financial capital tailored to it.

Updated Advisory Habits

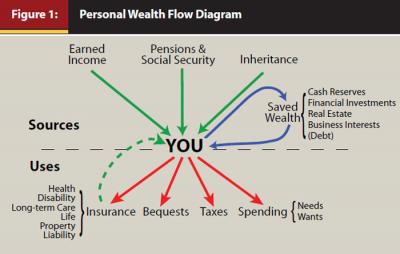

I’m finding that these ideas ring true with clients, in addition to being grounded in well-settled economic theory, required by the CFP Board Practice Standards, and consistent with life planning principles. To convey them, in addition to the 10 Core Planning Principles listed in the sidebar below, I am using the schematic in Figure 1 in conversations with clients.

In these discussions, we talk about smoothing the client’s ability to spend by moving wealth from good times to bad times in the safest way possible, and in a way that is consistent with the client’s values and preferences. Further talking points include:

- Note that you, that is, the client, not the portfolio, are at the center.

- Income and expenses are like currents going through you—and awkwardly, each to its own rhythm.

- This is a bounded system—total sources (the top half) has to equal total uses (the bottom half).

- Saved wealth is like a reservoir to assist in smoothing consumption.

- Insurance is mostly experienced as an expense. However, if there is a disruption in your personal life, for example, if you become disabled, insurance can bring some income into the system (through the dotted green arrow).

- For most people, in terms of sources, earned income is the place of most leverage—and thus a key focus, especially of life planning.

- In terms of uses, spending—in particular the distinction between needs and wants—is the place of most leverage, and thus also a key focus, again, especially of life planning.

In sum, financial planning means to orchestrate this delicate, finely tuned, always-in-motion system—a system that depends on a robust life planning process and incorporates the fruits of that life planning into a coherent economic model. Although this total picture is, I believe, the proper focus of financial planning, it is interesting that potential clients still sometimes come in thinking that it’s all about portfolio management and nothing more. In contrast, there is a bigger, more coherent picture to consider, with life planning in motion, hand in hand, with appropriate economic theory. In this light, financial planning can be defined as the lifelong process of integrating personal values with the management of both human and financial capital for the betterment of self and community. The adviser’s role is to facilitate that process.

References

Anderson, Carol, and Deanna L. Sharpe. 2008. “The Efficacy of Life Planning Communication Tasks in Developing Successful Planner-Client Relationships.” Journal of Financial Planning (June).

Anthes, William, and Shelley A. Lee. 2001. “Experts Examine Emerging Concept of Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning (June).

Bodie, Zvi. 1995. “On the Risk of Stocks in the Long Run.” Financial Analysts Journal 51 (May/June): 18–22.

Bodie, Zvi, and Paula Hogan. 2008. “The Emerging New Model for Wealth Management.” Private Wealth Management 1 (March).

Bodie, Zvi, and Robert C. Merton. 2000. Finance. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Bodie, Zvi, and Rachelle Taqqu. 2012. Risk Less and Prosper: Your Guide to Safer Investing. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Executive Leadership Center. The Future of Life-Cycle Saving and Investing. Conference series, Boston University. http://smg.bu.edu/exec/elc/lifecycle/index.shtml.

Hogan, Paula. 2007. “Life Cycle Investing Is Rolling Your Way.” Journal of Financial Planning (May).

Kinder, George, and Susan Galvan. 2007. “Psychology and Life Planning.” Financial Alert Magazine 17 (March).

Maton, Cicily Carson, Michelle Maton, and William Marty Martin. 2010. “Collaborating with a Financial Therapist: The Why, Who, What, and How.” Journal of Financial Planning (February).

Merton, Robert C. 2003. “Thoughts on the Future: Theory and Practice in Investment Management.” Financial Analysts Journal 59, 1 (January/February): 17–23. (Reprinted in Harvard College Investment Magazine, Spring 2005.)

Samuelson, Paul. 1994. “The Long-Term Case for Equities.” Journal of Portfolio Management 21 (Fall).

Acknowledgments: The author gratefully acknowledges suggestions from Carol Anderson, Zvi Bodie, Andrea Bulen, Marty Martin, Rick Miller, Don St. Clair, and Kent Smetters.

Sidebar:

10 Core Planning Principles

People care most about their lifetime level of living, not wealth. As you consider your own planning, are you targeting a specific portfolio amount in retirement, or are you thinking about a desired lifestyle? That’s a key question. It matters how you define financial success.

Absent a big inheritance, the most important determinant of your lifetime level of living is your human capital, your lifetime ability and willingness to earn income. Sobering but true; your personal gifts, and what you do with them, are the main levers for influencing your lifetime level of living. (In technical terms, human capital is the net present value of your lifetime earnings.)

Because protecting and enhancing human capital is of central importance, so also are education plans, career choices, work/leisure decisions, and the purchase of disability and life insurance designed to replace earned income if needed. Does your financial plan start with a careful analysis of the vibrancy and safety of your current and future income? Does your financial plan include protection from a disruption or loss of earned income? Are you thoughtful about how to maintain and improve your personal well-being? Physical and emotional well-being can also contribute to financial well-being.

Financial capital is complementary to human capital and should be tailored to it. In general, the riskier your earned income, the less risk you will likely want to take in your financial portfolio. (The recently unemployed don’t usually double up on stock exposure in order to “make up the difference” in income.) The more you expect your earned income to rise and fall with the markets, the less market exposure you will likely want in your financial portfolio. Despite what you might hear in the popular media, it’s not so much about risk tolerance (how much risk you are willing to bear), it’s fundamentally about risk capacity (how much risk you are able to take).

There is an overall boundary condition to funding lifetime hopes and dreams. Unless you die with debt, lifetime income (earned income, inheritances, Social Security, and pensions) must equal lifetime uses (taxes, insurance, bequests, personal spending). Thus, funding your personal goals requires specifying their importance to you and then funding these goals to the extent possible, subject to this lifetime income constraint, and with the least amount of risk. It’s true, we can’t have it all.

Risk is goal dependent. In general, the more strongly you care about a financial goal, the less risk you’ll want to take in financing that goal. Thus, your base lifetime standard of living, the lifestyle that you do not want to go below, is most appropriately funded with a safe investment that offers lifetime inflation-protected income. Goals that are more wants than needs can be funded with riskier assets.

Stocks are risky, even if held for a long time, and so are not appropriate when safe financing is required. In popular culture, there is a deeply rooted but fundamentally incorrect belief that if you have a long time horizon you can and should own stocks because stocks aren’t risky if held for the long term.

In the scientific worldview, that belief is a jaw-dropper for the following very specific reason: shortfall risk—the risk that the portfolio will not be at least equal to a specified level—increases with time. Need convincing? Try buying portfolio shortfall insurance: the longer the period the higher the premium.

What’s particularly important about this principle is how often it is ignored in popular culture. Remember, if your financial plan requires excellent stock performance to succeed, is it a plan or a hope?

Saving does not boost your lifetime level of living but instead smoothes your level of living. Savings shifts income from times of high earned income to lower earned income and from times of favorable life conditions to the more difficult personal times, for example of unemployment, disability, or death of the breadwinner. Saving and insuring are common strategies for resolving the reality that the rhythm of income rarely matches the rhythm of spending.

Useful risk management strategies include not just precautionary saving and diversification but also hedging and insuring. Hedging means to sell the upside potential of an asset in return for downside price protection. Insuring means to pay a known price to protect against the possibility of a larger loss on some risky asset while keeping the upside potential for the investment return on that asset.

When you plan from a risk-management perspective it is much more likely that you will decide to use insurance-based investment products, such as long-term-care insurance and inflation-indexed immediate annuities. Also, as strategies from the derivative markets become increasingly available to the retail investor, there will be a widening array of products that make use of synthetic securities to help you tailor investments to your particular planning needs.

Costs matter and should be transparent. Ensuring a low and transparent cost structure is also a core principle when following a scientific approach to personal wealth management. When you wring cost out of a portfolio, you put more money in your pocket. You will also likely get lower risk. (Higher-expense producers tend to ramp up risk in order to compete with their lower-expense peers.)