Journal of Financial Planning: August 2013

Executive Summary

- Designing retirement income portfolios is an important, and sometimes challenging, endeavor, with few existing comprehensive solutions. The relevant variables associated with the design process are numerous and complex.

- This paper presents a consistent approach for constructing a retirement portfolio using a combination of decision matrices. The matrices incorporate the relevant variables in a systematic way, but can be easily modified to suit client needs or the preferences of a financial planner.

- The approach described in this paper allows a firm to provide consistency in structuring the planning process, while offering some flexibility for individual financial planners.

H. Jeffrey Spivack, CFP®, AAMS®, serves as senior vice president and head of the wealth planning department at Janney Montgomery Scott. He directs internal strategic planning and is responsible for administering plan development and execution, as well as adviser education initiatives. He earned his masters in personal financial planning from the College for Financial Planning. (jspivack@janney.com)

Edward Nelling, Ph.D., CFA, is a professor of finance at Drexel University’s LeBow College of Business. He was previously on the faculty at Georgia Institute of Technology and has served as a visiting professor at The Wharton School and Korea University Business School. He is the author of the book Business Valuation Demystified. (nelling@drexel.edu)

Retirement income portfolio construction is a critical element in financial planning. Traditional financial planning often begins with a plan for retirement at its core, and then continues with financial strategies to meet the other needs of the client, from wealth transfer and tax minimization to other objectives. The period of retirement can encompass roughly the final 25 percent to 30 percent of an individual’s life and may represent the largest expense over his or her lifetime. It, therefore, makes sense to build resources and secure benefits for retirement first, following an approach that the financial services industry refers to as “lifetime cash flow planning,” a holistic way of visualizing wealth and the potential long-term impacts of decisions made over the course of an investor’s lifetime. Miccolis and Goodman (2012) point out that presenting a lifetime cash flow process is a tool that is powerful and that resonates well with clients.

The need to make retirement planning the primary focus of planning for many individuals is underscored by the fact that investors (and planners) do not know in advance the full time period or total cost of an investor’s retirement. Financial services providers have devoted significant resources to assisting clients in this area, seeking ways to calculate withdrawal rates that may be employed safely in guiding their clients.

Much has been written about retirement income planning. The focus is often on asset allocation and the corresponding withdrawal rate that is sustainable over a client’s lifetime. Bengen (1994) analyzed historical data and found that a 4 percent withdrawal rate was reasonable, with a portfolio allocation to stocks between 50 percent and 75 percent, and the remainder invested in intermediate-term Treasury securities. Cooley, Hubbard, and Walz (1999) found similar results. Pfau (2012) presented an approach resulting in higher sustainable withdrawal rates when the equity allocation is based on relative valuation levels, using the price earnings ratio of the aggregate market. Spitzer and Singh (2006) noted that the period over which withdrawals can be made depends on relative rates of return and tax considerations. Pye (2000) examined the effect of including Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) on withdrawal rates, and found that a withdrawal rate of 4 percent is sustainable over a 30-year horizon with 60 percent invested in stocks. Milevsky and Huang (2011) warned that an approach focusing on a single, sustainable withdrawal rate is too simplistic. They suggested that a more comprehensive approach is required, based on individual risk aversion and other circumstances.

Basu (2005) presented a modified version of the sustainable rate proposal by introducing age bands as a method to reduce errors in estimating expenses, algorithmically calculating replacement ratios to more closely approximate both need and resources. This paper applies age bands to retirement income portfolio design. Specifically, the purpose of this paper is to introduce an approach that will serve the long-term needs of practitioners seeking better ways to help their clients. The approach is flexible and practical, permitting a planner to incorporate subjective judgment in the adjustment of asset allocation levels in response to client needs and preferences. Of course, the planner’s expertise should guide the final recommendation to the client. However, some firms may want to impose some consistency across planners, provide additional guidance to recent hires, or modify their approach when new financial products are introduced.

The method presented in this paper facilitates this consistency, and presents a quantitative framework to consider complex risk factors. The approach uses a combination of decision matrices to construct a retirement portfolio based on a client’s situation and a firm’s service offerings. The matrices employed can be adapted to suit the strategies and product platform of the planner or firm. The matrices also can be used to incorporate, at least to some extent, the best practices of a firm’s planners.

Retirement Income Planning: Key Risks and How to Address Them

The challenges associated with effective retirement planning are significant. In particular, three primary sources of risk must be considered in any retirement plan: (1) longevity risk, (2) inflation, and (3) portfolio return volatility. These three factors are addressed in our approach to retirement portfolio construction.

The first factor is longevity. Over the past 150 years, the human life span in developed countries has effectively doubled. An infant born in the United States in 1860 had a life expectancy of 40 years. In 2002, that life expectancy had grown to 77 years, and by 2011 it stood at 82.5 years (Jones 2003).

A longer lifespan is associated with increased risk of outspending one’s assets. This risk, longevity risk, can have a significant effect on the design of a retirement portfolio. It is often addressed by including annuities, along with traditional assets such as stocks and bonds, in an individual’s portfolio.

Ameriks, Veres, and Warshawsky (2001) found that the inclusion of annuities in retirement portfolios improves portfolio sustainability. Milevsky and Huang (2011) noted that individuals may exhibit different levels of aversion to longevity risk, and retirees with greater risk aversion should expect lower sustainable withdrawal rates. Kaplan (2006) used a simulation to examine the effects of annuities on retirement portfolio value. The topic of longevity risk is also discussed in the book by Salsbury (2006). Our model addresses longevity risk by allowing annuities to be part of the retirement portfolio. This is an option that advisers and their clients can consider for inclusion, given a client’s specific needs.

Inflation is the second factor that impacts retirement portfolio construction. Inflation has varied over time, and has been moderate in recent years. Since 2005, the increase in the Consumer Price Index has averaged 2.3 percent per year. However, the movement in the aggregate price level tells only part of the story. Segments of the economy saw much sharper rises. For example, in 2011, energy rose 6.6 percent, after a 7.7 percent increase in 2010 (Crawford, Church, and Rippy 2011). Unsurprisingly, the segments that may be hardest hit in a potential inflationary cycle may be those that are essential for retirees: food, energy, health care, and utilities. Similar to Basu (2005), we allow the components of retirement expense to increase at different rates over time, instead of assuming a single aggregate inflation rate. Risks associated with long-term inflation are addressed implicitly through the age-banded nature of the technique, but may be further addressed explicitly by adding matrices based on alternative inflation scenarios.

Portfolio return volatility is also known to be of importance when constructing retirement portfolios. Investors need to bear risk if they wish to obtain returns greater than the risk-free rate. Traditionally, one of the guiding benefits offered through modern portfolio theory is the ability to manage portfolio volatility through diversification. All else being equal, the lower the correlation among asset class returns, the lower the risk of the portfolio. However, the recent financial crisis highlighted the possibility of systemic high-risk events to occur, in which correlations among asset classes, and thus portfolio risk, increase significantly. The declines in wealth that occurred in recent years highlighted the advantages of sound planning and portfolio management. Our approach emphasizes diversification to manage risk and enhance returns, as well as the opportunity to include a choice of guaranteed investment products, such as annuities, which provide income regardless of underlying movements in financial markets.

A New Approach

The approach to retirement income portfolio design detailed in this paper employs traditional asset allocation methods in combination with a decision-making matrix using guaranteed income products, such as variable and immediate annuities. Before describing the process, it is important to understand the key terms used.

- Investment assets are those assets that do not include a guaranteed income provision. Investment assets include equities, fixed-income securities, and cash. The allocation to these asset classes depends on a client’s risk tolerance, time horizon, and other traditional factors. This allocation also depends on a planner’s assumptions regarding capital markets.

- Annuities are financial products that accept and grow funds from an investor that will, upon annuitization, provide a stream of future payments. Annuities, in the context of this paper, are presumed to be either immediate or variable and to incorporate income guarantees for life, or guarantee monthly withdrawal options.

- Guaranteed income sources are sources of income that are guaranteed for life and generally associated, either directly or indirectly, with actuarial calculations. In the case of this retirement income planning strategy, these may include annuities (either immediate or variable so long as they include either guaranteed withdrawal benefits or a lifetime income option), pensions, Social Security, or other promissory resources.

- Retirement income is income used to service needs in retirement.

- Holistic lifetime cash flow planning is defined as visualizing a client’s current wealth and how planning elections may impact their wealth over time. Because the term of retirement may be quite long (the final 20 to 30 percent of life) and unpredictable, this is generally the largest component of a lifetime cash flow analysis.

We recognize that some investment assets, such as government bonds, provide a riskless stream of cash flows. However, these cash flows cease at maturity, and a client may outlive the instrument. As a result, we do not explicitly consider these instruments to be guaranteed assets. We recognize that there is some implicit substitutability between guaranteed assets and low-risk, income-producing investment assets. It is left to the judgment of the planner or firm to determine the extent of this substitutability and adjust the allocation appropriately based on the client’s situation.

Segment Clients by Age and Asset Level

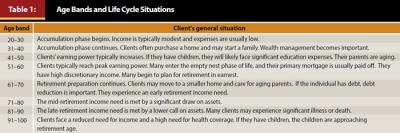

The first step in our approach is to segment clients by age, using the age-banding model of Basu (2005). Each age band identifies the typical considerations for the client. Over time, the client moves through the investment phases of wealth accumulation, wealth management, wealth preservation, and wealth distribution. The age bands and typical associated characteristics are described in Table 1.

The next segmentation of clients occurs based upon the assets available to fund retirement needs. Included with these assets can be the calculated present values of future benefit programs, such as pensions and other sources of income during retirement. The asset bands are defined in four categories: (1) low assets (less than $500,000); (2) moderate assets ($500,000 to $2 million); (3) high assets ($2 million to $5 million); and (4) ultra-high assets (more than $5 million). If the planner or firm finds that these ranges do not adequately describe their client universe, the bands can be modified.

Develop a Baseline Matrix

After segmenting clients by age and asset level, a baseline matrix for portfolio construction can be developed. The primary result from the baseline matrix is the allocation to guaranteed versus non-guaranteed assets (hereafter referred to as investment assets (non-guaranteed)). Guaranteed assets are designed to provide income to the client and/or their spouse or partner for the remainder of their lifetime(s). Typically, guaranteed assets take the form of an annuity (either immediate or variable), a pension, or some similar contract. The guaranteed assets may also incorporate a mechanism to protect the portfolio from market declines.

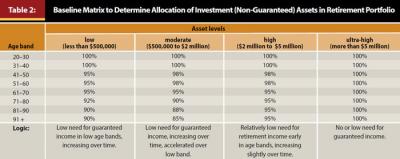

Table 2 presents a hypothetical baseline matrix based on client age band and asset level. The percentages displayed in the table represent the allocation to investment assets. The allocation to guaranteed assets is determined by subtracting the entry in the table from 100 percent. For example, a 75-year-old client with a moderate asset level would have a 10 percent allocation to guaranteed assets in the portfolio. The weightings in the matrices shown in this paper are representative. These are not the recommended weightings for a firm, but are used here simply for illustration purposes. The specific allocations are determined subjectively by the planner or firm, but in general, the allocation to guaranteed assets increases with age and decreases with asset level.

Most clients will have an “automatic” allocation to guaranteed assets through Social Security, and some clients also may have a defined benefit pension plan through their employer. These guaranteed assets can be considered in the allocation recommended by our model. For example, if a client portfolio calls for 12 percent in guaranteed assets, and the present value of future Social Security benefits is 4 percent of the portfolio, an additional 8 percent can be invested in annuities. The guaranteed asset recommendation by the model is a minimum, not a maximum, value, so if the present value of Social Security or pension benefits exceeds the recommended amount, it will not adversely affect the client.

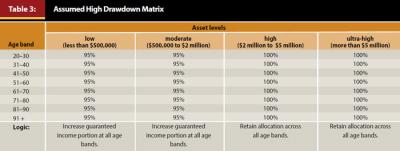

Successive matrices are then applied to the baseline decisions and act as further multipliers. Each matrix addresses either a single criterion in a binary manner (for example, if the client has a concentrated stock position) or different iterations of a single criterion (such as one matrix for a high-assumed-drawdown rate and a second matrix for a low rate), and can change the allocation to guaranteed assets. Multiplied together, the resulting portfolio recommendation is derived from the combination of matrices.

As an example, two matrices are presented in Tables 3 and 4 based on alternative assumptions regarding drawdown rates. The high drawdown scenario assumes a rate in excess of 4 percent, while the low drawdown scenario uses a rate below 3.5 percent. If the drawdown rate is in the typical range of 3.5 to 4 percent, these additional matrices are unnecessary.

A higher drawdown rate may be associated with a higher risk of asset depletion over retirement. Increasing the allocation to guaranteed assets such as annuities or pensions can help to mitigate that risk. This is why the percentages in the low and moderate asset level columns are less than 100 percent. At higher asset levels, changes to the guaranteed allocations may be unnecessary, because the client’s assets are likely to be sufficient to fund the higher drawdown rate. In contrast, a low drawdown assumption reduces the risk of asset depletion, and more of the portfolio can be allocated to investment assets, which are likely to provide higher returns at a lower cost over time.

Subjective limits or caps can be imposed on the final allocation. For example, if the result is calculated to be 110 percent in investment assets, it would be natural to cap the result at 100 percent. Similarly, if the decision was made that a client younger than 40 years old should not be considered for immediate annuities, the corresponding allocation for that age band could be set to 0 percent. These caps can be set by the planner or firm, based upon their views and understanding as to what is appropriate, and this may be done in consultation with clients.

Consider a 65-year-old client with a moderate asset level. The baseline matrix would call for 95 percent to be invested in investment assets. The high drawdown scenario would result in an allocation to investment assets of 90.25 percent, which is determined by multiplying the 95 percent value in the baseline matrix by the 95 percent value from the corresponding age and asset cell in the high drawdown matrix.

In contrast, the low drawdown scenario would result in an allocation to investment assets of 99.75 percent, which is determined by multiplying the 95 percent value in the baseline matrix by the 105 percent value from the appropriate cell in Table 4. If the resulting allocation was greater than 100 percent, planners would cap the value and invest 100 percent in investment assets. In addition to variables such as drawdown, the determination of the level of guaranteed assets is based on additional factors, as outlined in Table 5.

An additional set of matrices is used to establish the distinction between variable and immediate annuities as components of the primary analysis. The balance of the recommendation between variable and immediate annuities, as components of the portfolio, can be set at the discretion of the planner or the firm based upon their own preferences.

As noted earlier, the portfolio of investment assets would consist of equities, fixed-income securities, and other asset classes. The focus of this paper is on the decision matrix approach and the determination of the allocation to guaranteed assets based on retirement income need. As a result, we do not discuss the construction of the investment asset portfolio. This is left to the discretion of the planner or firm, which may have an internal approach to traditional asset allocation.

Retirement Income Portfolio Case Studies

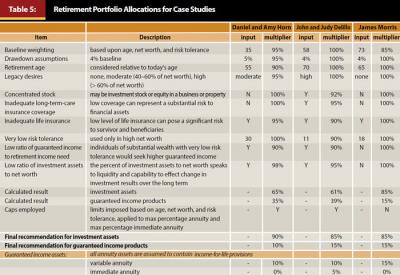

The following examples illustrate the application of the technique presented earlier through the use of case studies. The clients in the case studies are fictional but representative of typical planning sessions. Each analysis begins with a baseline calculation that determines the allocation to investment versus guaranteed assets based on client age and level of assets. The allocation is then further modified using multipliers to address other relevant factors. After determining this calculated result, the planner or firm may wish to impose a cap on the allocation to guaranteed assets. The allocation to guaranteed assets can be subdivided further to determine the amount of variable versus immediate annuity products, after considering the client’s other sources of guaranteed income such as pensions.

Note that the individual multipliers for each variable are developed at the discretion of the planner or firm. These multipliers could be determined subjectively or using a quantitative approach. For example, relatively young clients with inadequate life insurance will typically reduce their allocation to investment assets. As a result, their multiplier for that variable will be less than 100 percent. The exact value for the multiplier, such as 95 percent or 90 percent, is determined by the planner.

Case Study 1: Daniel and Amy Horn, Young with High Cash Flow

Daniel and Amy are in their 30s. Their assets are low, but cash flow is high due to Daniel’s salary of $170,000 per year. They have a high tolerance for risk and have invested aggressively in the past. Daniel would like to retire at age 55, and his spending habits suggest a probable high drawdown rate in retirement. He and Amy would like to leave at least $200,000 to each of their three children. If the baseline calculations and additional multipliers are applied as shown in Table 5, an allocation of 65 percent in investment assets with the remaining 35 percent of the portfolio in guaranteed assets can be calculated (0.95 x 0.95 x 0.90 x 0.95 x 1.00 x 1.00 x 0.95 x 1.00 x 0.90 x 0.98).

Some planners might conclude that this is an unreasonably large allocation to guaranteed assets. There are two ways to modify the approach to address this possibility. The first method would be simply to impose a maximum cap on the allocation to guaranteed assets. If a planner or firm followed this approach and capped this category at 10 percent, the final recommendation would be 90 percent in investment assets and 10 percent in guaranteed income products, further allocated to 10 percent in variable annuity products and no allocation to immediate annuity products. Such capping can be employed as a technique by the planning firm to allow for their own platform product capabilities, as well as their own investment philosophy, which may differ between firms or planners.

An alternative to imposing caps would be to revise the percentages in the decision matrices to increase the allocation to investment assets. This would be appropriate if a planner found that most recommendations resulted in the use of caps. In this case, it would be better to revisit the assumptions in the individual matrices and modify them to produce a more realistic result. Indeed, this flexibility is one of the main advantages of using the decision matrix approach.

After determining the allocation to investment assets, the planner could then construct a portfolio with a mix of stocks, bonds, and other assets that would depend upon the couple’s risk tolerance, investment horizon, liquidity needs, and other factors.

For Daniel and Amy, the recommendation for 10 percent accumulation of guaranteed income products comes as a function of their relatively low level of assets, their young age, their high income, and their objective of retiring at a young age. Daniel and Amy are relatively young, with plenty of time to accumulate wealth derived from Daniel’s high salary. They would benefit from having a comprehensive financial and estate plan with a focus on implementing a retirement cash flow analysis.

Case Study 2: John and Judy Delillo, Business Owners with High Net Worth

John and Judy are both 58 years old. They own a successful business selling hardware supplies to contractors and industrial builders. They each work for the company, and their combined annual income is high ($480,000). Their overall net worth is also high (approximately $8 million) but much of that net worth (85 percent) is tied up in the equity for their business.

The couple is relatively conservative, preferring to preserve what they have instead of trying to aggressively increase returns. They do not anticipate selling their business, and they would like to leave it to their children when they die. They anticipate retiring at age 70, at which time the children will either run the business or hire someone else to do so. They currently have no life insurance and only basic health insurance. When both have passed away, they would like to leave $2 million to charity.

Following the procedure outlined in the first case study, the calculated allocation to investment assets is 61 percent. If it is again assumed that caps will be employed, the final recommendation is 85 percent in investment assets and 15 percent guaranteed income products. The guaranteed assets would have 10 percent in variable annuity products and 5 percent in immediate annuity products. A further cap is included in the model for highly conservative high net worth individuals that would limit the percentage of assets exposed to risk through variable investment and guaranteed products.

John and Judy’s situation is affected by their concentrated equity position within the business. Although they have substantial time to continue to gather assets (12 years), their plans have substantial business risk—perhaps more risk than is consistent with their determined risk objective. They are further hampered by their lack of life and health insurance, both of which pose significant threats to their financial position. Accumulating guaranteed income resources between now and retirement seems appropriate.

Case Study 3: James Morris, Widower with Moderate Net Worth

James is a 73-year-old widower with a moderate net worth of about $1.5 million. He enjoys a good pension from his former job as a schoolteacher, a smaller survivor pension from his late wife, and his Social Security benefits. His expenses currently exceed his income, requiring him to use his savings to a certain extent. He has two children, both of whom are grown and financially independent. He does not anticipate having to support his children or grandchildren. He is moderate in risk tolerance and enjoys watching the market, occasionally buying stocks and bonds.

The Morris family is known for its longevity; James’ parents and grandparents lived well into their 90s. He is therefore concerned that his assets may not last. Although James has long-term-care insurance from his former employer that he continues to pay for, he does not have any life insurance and would like to leave $500,000 to a foundation he established years before in the name of his wife. The calculated results for James are 85 percent in investment assets and 15 percent in guaranteed income products. No caps are required, and the 15 percent in guaranteed income products should be invested in variable annuities.

This example is a fairly typical situation for many present retirees, with a defined benefit program providing much of James’s needed income. Given that James has a moderate risk tolerance and a concern with longevity, placing some of his assets in a variable product with income guarantees for life makes sense. With the family history of longevity, and the excess of James’s expenses over his income, it is probable that he may see principal declines in his assets. However, as much of his income is currently covered by sources guaranteed through life, increasing his investment portfolio’s allocation to higher return assets, such as equities, may help offset his long-term usage of his principal assets.

Conclusions

Establishing an ideal portfolio for a client planning for retirement can be a significant challenge, for which there are few existing comprehensive solutions. This paper has introduced a method for constructing a retirement income portfolio using a combination of decision matrices.

After segmenting clients based on age and asset level, additional variables to determine the portfolio allocation to guaranteed assets, such as annuities, can be considered. The remainder of the portfolio can be allocated to investment non-guaranteed assets, including equities and fixed-income securities. Subjective judgment, mean-variance analysis, or other approaches can then be used to determine specific asset class weights.

The advantages of employing this strategy in designing client portfolios is that the baseline characteristics and other criteria may be adjusted to suit the strategies, tactics, and product platforms of the planner and his or her firm. The strategy also can be adjusted to address individual client situations.

Finally, the successful navigation of retirement for an investor requires a dynamic approach that incorporates a systematic method for monitoring and adjustment. The method described in this paper facilitates such an approach, and is designed to incorporate the relevant elements of a client’s financial situation into a holistic recommendation.

References

Ameriks, John, Robert Veres, and Mark J. Warshawsky. 2001. “Making Retirement Income Last a Lifetime.” Journal of Financial Planning 14 (12): 60–76.

Basu, Somnath. 2005. “Age Banding: A Model for Planning Retirement Needs.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 16 (1): 29–36.

Bengen, William P. 1994. “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial Planning 7 (4): 171–180.

Cooley, Philip L., Carl M. Hubbard, and Daniel T. Walz. 1999. “Sustainable Withdrawal Rates from Your Retirement Portfolio.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 10 (1): 39–47.

Crawford, Malik, Jonathan Church, and Darren Rippy. 2011. “CPI Detailed Report Data for December 2011.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor. www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid1112.pdf.

Jones, Becca. 2003. “Executive Summary—Population Glossary.” Population Resource Center, February. Accessed June 19, 2013. http://economistindia.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/population_glossary.pdf.

Kaplan, Paul D. 2006. “Asset Allocation with Annuities for Retirement Income Management.” Journal of Wealth Management 8 (4): 27–40.

Miccolis, Jerry A., and Marina Goodman. 2012. “The Extended Influence of ‘Safe Withdrawal Rate’ Research.” Journal of Financial Planning 25 (9): 28–29.

Milevsky, Moshe A., and Huaxiong Huang. 2011. “Spending Retirement on Planet Vulcan: The Impact of Longevity Risk Aversion on Optimal Withdrawal Rates.” Financial Analysts Journal 67 (2): 45–58.

Pfau, Wade D. 2012. “Withdrawal Rates, Savings Rates, and Valuation-Based Asset Allocation.” Journal of Financial Planning 25 (4): 34–52.

Pye, Gordon B. 2000. “Sustainable Investment Withdrawals.” Journal of Portfolio Management 26 (4): 73–83.

Salsbury, George. 2006. But What If I Live? The American Retirement Crisis. Cincinnati, Ohio: National Underwriter.

Spitzer, John J., and Sandeep Singh. 2006. “Extending Retirement Payouts by Optimizing the Sequence of Withdrawals.” Journal of Financial Planning 19 (4): 52–61.