Journal of Financial Planning; August 2013

Executive Summary

- Two unconventional strategies for claiming Social Security benefits (“claim and suspend” and “claim now, claim more later”) have the potential to pay higher lifetime benefits to some individuals and increase costs within the Social Security system.

- “Claim and suspend” allows an individual who has reached full retirement age to claim benefits and then immediately suspend them, either to put his or her own benefits on hold if reentering the workforce, or to allow a spouse to claim a spousal benefit while the individual continues to work and earn delayed retirement credits. The beneficiaries are either one-earner couples or those in which one spouse’s earnings are small relative to the other’s.

- In the “claim now, claim more later” strategy, a married individual at or past full retirement age claims a spousal benefit while delaying claiming his or her own retired-worker benefit to build up delayed retirement credits. The more equal the lifetime earnings of the spouses are, the more they have to gain. Using this strategy, couples can potentially gain between 2.6 and 3.1 percent of their base lifetime Social Security benefits.

- We estimate the potential cost of allowing couples the option of “claim and suspend” to be about $0.5 billion dollars a year, while that of “claim now, claim more later” to be around $10 billion a year. It is possible that policymakers may evaluate these strategies as they look to trim expenses by reducing cost increasing provisions to ensure they are consistent with the basic goals of the Social Security program.

Alicia H. Munnell, Ph.D., is the Peter F. Drucker Professor of Management Sciences at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management and the director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. (munnell@bc.edu)

Alex Golub-Sass is a senior analyst at FI Consulting in Arlington, Virginia. He holds an M.A. in economics from the University of Virginia.(agolubsass@gmail.com)

Nadia S. Karamcheva, Ph.D., is a research associate at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C. She holds Ph.D. and M.A. degrees in economics from Boston College. (nkaramcheva@urban.org)

Note: The research reported herein was pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement Research Consortium (RRC). The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of SSA, any agency of the federal government, the RRC, Boston College, or the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders.

When to claim Social Security is one of the most important decisions Americans make when approaching retirement, as the claiming age can have a significant impact on lifetime benefits and overall retirement security. The dependable stream of income provided by Social Security is particularly valuable at a time when global financial market uncertainty has underscored the risks associated with 401(k) plans. In this climate, financial planners and their clients may more closely consider the best way to utilize Social Security.

This paper evaluates two Social Security claiming strategies that have rarely been used but recently have received more attention (Hershey 2008; Ruffenach 2012). The two strategies are: (1) “claim and suspend” in which an individual claims benefits but then suspends them, either to put his or her own benefits on hold if he or she decides to reenter the workforce or simply to allow the spouse to claim a spousal benefit; and (2) “claim now, claim more later” in which an individual initially claims a spousal benefit while delaying claiming his or her own worker benefit to build up delayed retirement credits.1 Each of these unconventional claiming strategies has the potential to pay higher lifetime benefits to some individuals and increase system costs.

The number of households adopting these strategies could increase for several reasons, including (1) increased publicity, (2) the need to maximize retirement resources, (3) the growing number of older Americans in general and two-earner couples in particular, and (4) the recent advent of an actuarially fair delayed retirement credit. At the same time, however, the Social Security program faces a long-term financing challenge, so any claiming strategies that could increase costs to the system should be carefully evaluated to ensure that they serve a compelling policy objective. In addition to identifying the type of individuals who can potentially benefit from these strategies, this paper also addresses the policy issues by estimating the costs of a widespread adoption of the two strategies.

Background

Currently, retired workers can choose between claiming benefits at their full retirement age (FRA)2 and receiving full benefits, claiming as early as age 62 but receiving reduced benefits, or delaying retirement to as late as age 70 and collecting higher benefits. The reductions and the delayed retirement credits are approximately actuarially fair for a person with average life expectancy. Early retirement benefits are lowered by an amount that offsets the longer period for which they will be received. The delayed retirement option offers higher benefits but for a shorter remaining lifetime. Thus, on average, workers will receive the same lifetime benefits regardless of when they claim between the ages of 62 and 70. A recent study (Sun and Webb 2009) has explored a further consideration that could factor into the claiming decision—the longevity insurance value provided by Social Security.

For married households, the situation is more complicated, because different types of benefits are available and the claiming behavior of one spouse often affects the benefits of the other. In addition to retired worker benefits, married households can potentially receive spousal benefits and/or survivor benefits. A spousal benefit, if claimed at or after the FRA, is equal to half of the worker beneficiary’s base benefit. A survivor benefit provides a surviving spouse with the full amount of the decedent’s actual benefit. The amount can be lower if the individual chooses to receive either the retired worker benefit or the spouse’s benefit before the FRA. However, spouses’ benefits are not affected by the age at which the worker beneficiary claims benefits.

Given the variety of options, previous research has examined what claiming strategies households could use to maximize the expected present value of their benefits (EPVB). Looking at prototypical households, Munnell and Soto (2005) showed that the maximizing claiming ages depend on the age difference between the spouses and the relative sizes of each spouse’s primary insurance amounts (PIAs), which is defined as the monthly benefit individuals receive at the FRA. In general, if the wife’s PIA is more than 40 percent of her husband’s PIA, the household’s Social Security wealth is maximized if the woman claims as soon as possible and the husband delays until 69. If the wife’s PIA is very small, lifetime benefits are maximized if the wife claims at the same time as her husband, usually after the husband has reached the FRA. Similarly, Coile et al. (2002) found that in the case of one-earner couples, the household maximizes its lifetime benefits if the husband claims at 65, assuming the wife claims at the same time.

While both of the above studies found that couple’s lifetime benefits are generally greatest if the husband claims at 65 or later, the majority of married men actually claim earlier. Using administrative data from the Social Security Administration’s New Beneficiary Data System for mid-1980 to mid-1981, Coile et al. (2002) noted that most men claimed as soon as they became eligible or soon thereafter. Sass, Sun, and Webb (2007) examined households in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and compared the EPVB from households’ actual claiming behavior to the EPVB of optimal claiming behavior. The authors found that the couple’s lifetime benefits are almost always greater if the husband claims benefits several years later. The resulting loss from this suboptimal behavior is around 4 percent of a household’s EPVB.

To help explain claiming behavior, other studies have looked at differences in subjective mortality beliefs. Hurd, Smith, and Zissimopoulos (2004) found that people with very pessimistic subjective mortality beliefs claimed earlier, but that the effects were not large. Like previous studies, they concluded that most households leave money on the table by claiming earlier than the ages that would maximize lifetime benefits. Other authors have relied on the structural approach to explain the effects of Social Security rules on claiming ages and retirement behavior (see Gustman and Steinmeier 2004, 2005, 2009).

This paper builds on the previous literature by analyzing how “claim and suspend” and “claim now, claim more later” may affect a household’s optimal claiming strategy. As in the earlier studies, we assume that an individual will choose to claim at an age that maximizes EPVB, and that a couple will behave cooperatively and choose each spouse’s claiming age so as to maximize the couple’s joint EPVB. As a result, for each household in the HRS, we are able to compare the maximum EPVB under conventional claiming behaviors to the maximum EPVB using these strategies. The difference is the additional Social Security wealth that the household can gain from using these strategies. The gain to the household is the cost to the system. Using the actual number of eligible households allows us to also calculate the potential cost to Social Security and its distributional implications.3

Methodology and Data

To understand the benefit and cost implications of the two strategies on the actual population of retirees, rather than hypothetical workers, we use data from the 2006 HRS and focus on the joint claiming decisions married couples must make when the eldest member is 62. Using life tables that vary by gender, race, and education, we calculate the total expected benefits, including survivor benefits, paid to each household at each possible combination of claiming ages under conventional claiming strategies. The goal is to compare the lifetime benefits of couples when they can take advantage of each of the two strategies with the lifetime benefits under conventional claiming rules. We assume that under each scenario the household will choose their claiming ages to maximize the expected present discounted value of their lifetime Social Security benefits. (For a detailed explanation of how each household solves the benefit maximization problem, see the appendix at the end of this article).

Our calculations are based on the 1948 cohort life table. To find the expected lifetime benefits under the two scenarios, we use a 3 percent real discount rate and the socioeconomic survival rates from Brown, Liebman, and Pollet (2002), which determine relative survival probabilities for 12 race-gender-education groups. If an individual did not fall into one of the 12 groups, they were assigned gender-specific cohort mortality.

“Claim and Suspend” Strategy

The Great Recession wreaked havoc on retirement savings, forcing many Americans to reassess their retirement plans. For example, some decided to work longer or, if already retired, to re-enter the workforce.4 For those workers re-entering the labor force, the annual retirement earnings test and the claim and suspend option allow them to enhance future benefits by having benefits withheld while they work.

Those who have already claimed their Social Security benefits and are under the FRA will find their benefits automatically reduced when they go back to work. In 2013, for each dollar of earnings in excess of $15,120, benefits are reduced by $1 for each $2 earned. Many economic studies have shown that this annual earnings test discourages work because most beneficiaries are unaware that the reduction in benefits while working triggers an increase in benefits later. In fact, benefits foregone while working are in effect rolled forward to increase individuals’ Social Security benefits after they reach the FRA.

Consider the following example. Assume that a person started to collect Social Security at age 62, but she continued to work and only retired for good at 63. If that person earned so much that half her benefits were withheld, at the FRA the benefit would be raised to what it would have been if she had claimed at age 62½. On average, the benefit a retiree receives is equal to the amount he or she would have received if the annual earnings test were never applied.

In some instances, the annual earnings test causes individuals to be worse off than had they not claimed before the FRA. Consider an individual who claims benefits at 62 but continues working until age 63. If her salary is so high that her benefits are completely withheld, upon reaching the FRA she will be treated as if she claimed at 63. However, the recalculation will not take into account the fact that the she did not receive a higher benefit for the time between when she stopped working and the FRA.

Those over the FRA who go back to work have a much more flexible option. As a result of the Senior Citizens’ Freedom to Work Act of 2000, they are no longer subject to the annual earnings test but rather can voluntarily claim and suspend (U.S. Social Security Administration 2000). That is, they can either work and receive full benefits or voluntarily suspend payments. If they choose to suspend, they forfeit current benefits but earn delayed retirement credits for a permanent increase in their future monthly benefits. This strategy can be very helpful to those who earn enough to support themselves, because it allows them to increase the amount of future monthly Social Security benefits.

In essence, “claim and suspend” is a continuation of the annual earnings test. In both cases, the retiree forgoes benefits while working for an actuarially increased benefit in the future. In both cases, if the individual has a spouse, the survivor benefit is increased to the extent that it is based on the higher earner’s actual benefit. If the individual has a spouse, “claim and suspend” leaves the spousal benefit unaffected, but the annual earnings test will reduce spousal benefits that are based on the worker’s earnings record. The two strategies differ in that one is mandatory and one is voluntary. They also differ in the timing of the increase. Under the annual earnings test, higher benefits are provided only once the worker attains the FRA. Under “claim and suspend” higher benefits are payable as soon as the worker re-claims.

“Claim and suspend” for one-earner couples. As noted earlier, married individuals are entitled to a retired worker benefit based on their own earnings and/or a spousal benefit. In the case of one-earner couples where the wife did not work the necessary 40 quarters to qualify for a retired worker benefit based on her own record, she is eligible only for a spousal benefit. For her to start receiving a spousal benefit, however, her husband needs to have claimed his own retired worker benefit. The “claim and suspend” strategy allows a husband who reaches the FRA to claim and immediately suspend benefits, allowing his wife to receive a spousal benefit based on his earnings record. The husband is then free to continue working and receive delayed retirement credits, increasing not only his monthly benefit but also his wife’s survivor benefit. By using “claim and suspend” in this way, the couple can enhance the value of their lifetime benefits.

“Claim and suspend” for dual-earner couples. Prior research has shown that couples maximize their expected lifetime benefits by having the wife claim early and the husband claim late (Munnell and Soto 2005). The intuition is that the wife will receive her relatively low spousal benefit and/or benefit based on her own earnings only over the relatively short expected lifetime of her husband rather than over the relatively long expected life of the average woman. Therefore, the wife, like a beneficiary with an expected short life, should claim early. The wife’s survivor benefit, which she will receive after her husband dies, depends on her husband’s actual benefit. To get as high a survivor benefit as possible, the husband should continue working as long as possible. Thus, in many cases, the optimal claiming ages for the husband and wife are 70 and 62, respectively.

For the typical couple in which the wife is three years younger than her husband, this optimal claiming strategy is reasonably feasible with the “claim and suspend” strategy. The husband can claim his benefits at today’s FRA of 66, allowing his wife at age 63 to start collecting her spousal benefit. He can then suspend his benefit and increase the monthly amount by working to age 70. Without “claim and suspend,” however, the typical couple cannot achieve this optimal strategy. The wife would have to wait until age 67 before she could claim. Thus, the couple’s options would be constrained. Of course, if the wife is the higher earner and is older than the husband, the strategy can work in reverse. In addition, “claim and suspend” can be used by couples in conjunction with the “claim now, claim more later” strategy discussed later.

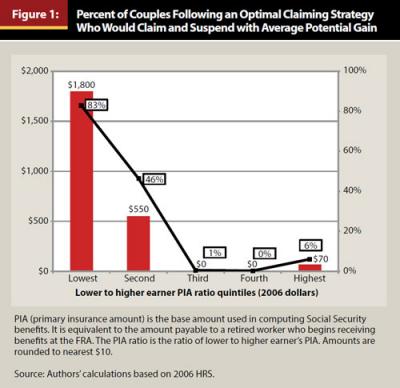

Overall, a relatively small portion (27 percent) of couples benefit from “claim and suspend.” The beneficiaries are either one-earner couples or those in which one spouse’s earnings are very small relative to the earnings of the other spouse, expressed as the ratio of lower to higher earner’s PIA (see Figure 1). Gains are concentrated mostly in the bottom and second PIA ratio quintiles (83 percent of those in the bottom and 46 percent of those in the second quintile can potentially benefit by using this strategy). However, even for those couples who benefit, the average lifetime gain is quite modest ($1,800 dollars on average for those in the bottom, $550 for those in the second quintile, and trivial amounts for the remainder).

“Claim Now, Claim More Later” Strategy

The second strategy, which is known as “claim now, claim more later,” is only available to married couples. As previously noted, married individuals are entitled to a retired worker benefit based on their own earnings and/or a spousal benefit. Prior to reaching FRA, when a married individual files for benefits, he or she is subject to a “deemed filing” provision. Under this provision, it is assumed that the individual is filing for both the spousal benefit and the benefit based on his or her earnings record. The Social Security Administration then compares the two benefits and awards the higher. After reaching the FRA, deemed filing no longer applies, giving the individual the ability to choose which benefit he or she receives. As a result, married individuals can claim a spousal benefit at age 66 and switch to their own retired worker benefit at a later date. This approach allows a worker to begin claiming one type of benefit while still building up delayed retirement credits, resulting in a higher worker benefit later.

Originally, we thought “claim now, claim more later” would involve the wife receiving the spousal benefit in two-earner couples with roughly equal earnings. For example, consider a two-earner couple in which the husband is three years older than the wife (the typical age difference according to the HRS). Both husband and wife had originally planned to delay claiming until age 70 to receive the highest possible monthly benefit. But, instead, once the husband claims his benefits at age 70, the wife (now age 67 and no longer subject to deeming) can file for just a spousal benefit. The wife then continues working and contributing to Social Security. At age 70, she files for her own retired worker benefit, which has now reached its maximum amount due to the delayed retirement credits, and she stops receiving the spousal benefit. In this situation, the wife gains three years of spousal benefits that she would not have enjoyed under the conventional claiming approach.

But it turns out that those most likely to receive a spousal benefit while using the “claim now, claim more later” strategy are the husbands in two-earner couples. As noted earlier, previous research has found that married women will maximize the couple’s expected lifetime benefits by claiming early. As a result, the way an optimizing couple would use “claim now, claim more later” is for the wife to claim at age 62 and, once her husband reaches age 66, he would claim a spouse’s benefit based on his wife’s earnings. At age 70, he would claim the maximum amount of his own retired worker benefit due to the delayed retirement credits and stop receiving the spousal benefit. Of course, if the woman is the higher earner, the story works in reverse.

The final issue is determining who gains from the availability of the option to claim spousal benefits and then claim their own. Some obvious criteria include: (1) the individuals must be married, (2) at least one member of the couple must be healthy enough to delay claiming until age 66, and (3) both spouses must have an earnings history.

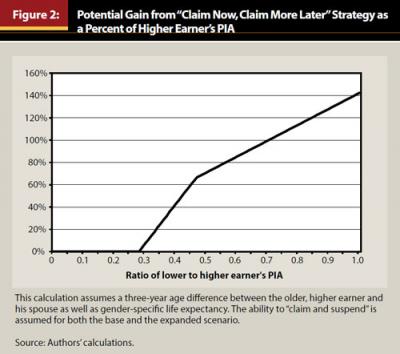

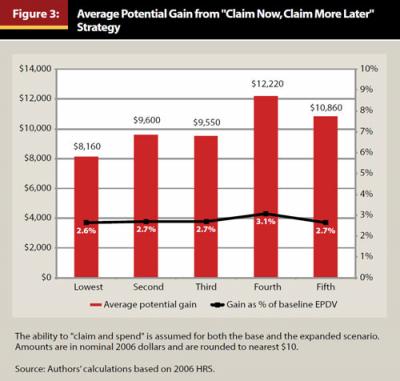

The higher and the more equal their earnings records, the more can be gained. Figure 2 shows the household’s potential gain as a monotonically increasing function of the lower to higher earner PIA ratio. Generally, the potential benefits from “claim now, claim more later” are relatively evenly distributed, though they somewhat favor households in the top two quintiles of the wealth distribution (see Figure 3). Overall, 83 percent of the couples in the sample can potentially benefit from the use of this strategy. Their average gain varies between 2.6 percent and 3.1 percent of their baseline EPDV of Social Security benefits, or between $8,160 and $12,220 in nominal 2006 dollars.5

Effects on the Social Security System

A net positive gain to a household as a result of using one of the strategies corresponds to a net loss, or cost to the Social Security system. To calculate the overall annual impact on the system’s costs, we apply HRS weights to the average gains made by couples using the strategies and then multiply those averages using the actual number of men and women age 62 in the 2006 Current Population Survey. (For details on the calculations see the online appendix at the end of this article).

Given the low average gains that we estimated, it is not surprising that the total cost of the “claim and suspend” strategy is relatively low (approximately $0.5 billion per year). Moreover, this estimate assumes that couples follow an optimal claiming strategy, even though evidence suggests that many do not. In addition, the “claim and suspend” option has a clear policy rationale. The Senior Citizens’ Freedom to Work Act, which authorized its use, was designed to help people work longer. “Claim and suspend” does just that. Individuals re-entering the workforce can use it to earn delayed retirement credits. Additionally, one-earner couples can use it to initiate a spousal benefit while the primary earner continues to earn delayed retirement credits.

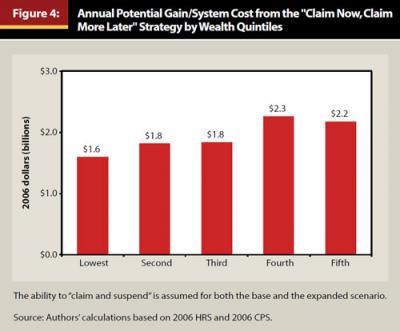

Next we calculated the annual system’s cost of “claim now, claim more later.” While conventional claiming behavior would have produced maximum benefits of $339.8 billion for married couples in 2006, the expanded options of “claim now, claim more later” would have resulted in maximum benefits of $349.5 billion. Therefore, the potential annual cost to Social Security is $9.7 billion. We assume that, under the conventional strategy, couples claim benefits at the optimal ages that maximize their expected lifetime benefits. In reality, as previously noted, they tend to claim early. If we use actual claiming behavior as the base case, rather than optimal behavior using conventional strategies, the potential cost would be about $23.3 billion rather than $9.7 billion.

Figure 4 shows that the Social Security system’s total costs associated with this strategy are relatively evenly distributed, with the top two wealth quintiles receiving roughly 45 percent of the total benefits.

Implications for Financial Planners

The takeaway for financial planners is that the use of these two unconventional strategies can potentially increase the overall expected Social Security wealth of their clients. The two strategies increase the claiming options of couples where spouses’ retirement decisions often interact. The “claim and suspend” strategy allows the higher earner to keep working and earning delayed retirement credits while the lower earner collects a spousal benefit. The “claim now, claim more later” strategy allows the higher earner to collect a Social Security spousal benefit while continuing to work and earn delayed retirement credits; at retirement, this individual then switches from claiming a spousal benefit to claiming a higher retired worker benefit. Under both strategies, working longer allows the higher earner to boost the size of the eventual survivor benefit that the lower earner will receive if the lower earner outlives the higher earner.

Conclusion

The financial crisis that began in 2008 underscored the importance of Social Security as the backbone of the retirement income system. However, with the aging of the population, Social Security is facing shortfalls that will require modifications to the current system. Therefore, policymakers will be looking for ways to trim costs. This paper examined two little-used provisions that recently have received more attention and that could potentially be used by households to increase their Social Security benefits.

The “claim and suspend” strategy allows individuals to claim benefits and then immediately suspend them, either to put his or her own benefits on hold if re-entering the workforce or to allow his or her spouse to claim a spousal benefit while continuing to work and earn delayed retirement credits. The beneficiaries are either one-earner couples or those in which the wife’s earnings are very small relative to the husband’s, and the average gain is relatively small. The annual cost to the system is about $0.5 billion.

In contrast, more than 80 percent of couples on the verge of retirement have the potential to gain from the “claim now, claim more later” strategy. The main beneficiaries are two-earner couples. A significant portion of the benefit goes to those with higher incomes and those with more equal lifetime earnings of the spouses. The potential cost in 2006 was about $9.7 billion. This cost will climb sharply as large numbers of baby boomer couples start retiring and the strategy gains popularity.

Endnotes

- A working paper version of this study examined one more strategy, “Free Loan from Social Security,” which we estimated to cost between $5.5 billion to $11 billion annually and pointed out the lack of clear policy rationale behind its existence (see Munnell et al. 2009). As a result, in December 2010 the Social Security Administration announced the suspension of the option. See Social Security Administration (2010).

- The FRA is scheduled to increase from age 65 to 67 by 2022. The increase began with individuals born in 1938, for whom the FRA is 65 plus two months, and increases two months per year until it reaches age 66. After a 12-year hiatus, the FRA again increases by two months per year until it reaches age 67 for individuals born in 1960 or later.

- The actual cost to Social Security could be higher or lower depending on how close actual claiming behavior is to “optimal” claiming behavior in the past and how that pattern changes due to the introduction of the unconventional provisions. This line of analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, but is an interesting avenue for future research.

- See Sok (2010).

- Given the low cost of the “claim and suspend” strategy and its clear policy rationale of encouraging work at older ages, when calculating the gains and costs of the “claim now, claim more later,” we assumed that the ability to claim and suspend is available under both the base case and the strategy.

References

Brown, Jeffrey R., Jeffrey B. Liebman, and Joshua Pollet. 2002. “Estimating Life Tables that Reflect Socioeconomic Differences in Mortality.” In The Distributional Aspects of Social Security and Social Security Reform, edited by Martin Feldstein and Jeffrey B. Liebman, 447–457. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press for NBER.

Coile, Courtney, Peter Diamond, Jonathan Gruber, and Alain Jousten. 2002. “Delays in Claiming Social Security Benefits.” Journal of Public Economics 84 (3): 357–385.

Gustman, Alan L., and Thomas L. Steinmeier. 2009. “How Changes in Social Security Affect Recent Retirement Trends.” Research on Aging 31(2): 261–290.

Gustman, Alan L., and Thomas L. Steinmeier. 2005. “The Social Security Early Entitlement Age in a Structural Model of Retirement and Wealth.” Journal of Public Economics 89 (2–3): 441–463.

Gustman, Alan L., and Thomas L. Steinmeier. 2004. “Social Security, Pensions and Retirement Behaviour within the Family.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 19 (6): 723–737.

Hershey, Robert D. Jr. 2008. “You Can Have Your Benefits and Defer Them, Too.” The New York Times, October 22. www.nytimes.com/2008/10/23/business/retirement/23REPAY.html?_r=0.

Hurd, Michael D., James P. Smith, and Julie M. Zissimopoulos. 2004. “The Effects of Subjective Survival on Retirement and Social Security Claiming.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 19 (6): 761–775.

Munnell, Alicia H., and Mauricio Soto. 2005. “Why Do Women Claim Social Security Benefits So Early?” Issue in Brief 35. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H., Steven A. Sass, Alex Golub-Sass, and Nadia S. Karamcheva. 2009. “Unusual Social Security Claiming Strategies: Costs and Distributional Effects.” Working Paper 2009-17. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/wp_2009-17-508.pdf.

Ruffenach, Glenn. 2012. “The Baby Boomer’s Guide to Social Security.” The Wall Street Journal. June 1. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119514459625294332.html.

Sass, Steven, Wei Sun, and Anthony Webb. 2007. “Why do Married Men Claim Social Security Benefits so Early? Ignorance or Caddishness?” Working Paper 2007-17. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. crr.bc.edu/working-papers/why-do-married-men-claim-social-security-benefits-so-early-ignorance-or-caddishness/.

Sok, Emy. 2010. “Record Unemployment Among Older Workers Does Not Keep Them Out of the Job Market.” Issues in Labor Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Summary #10-04. www.bls.gov/opub/ils/summary_10_04/older_workers.htm.

Sun, Wei, and Anthony Webb. 2009. “How Much Do Households Really Lose by Claiming at 62?” Working Paper 2009-11. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. crr.bc.edu/working-papers/how-much-do-households-really-lose-by-claiming-social-security-at-age-62/.

U.S. Social Security Administration. 2000. “The President Signs the ‘Senior Citizens’ Freedom to Work Act of 2000.’” Social Security Legislative Bulletin. April 7. www.ssa.gov/legislation/legis_bulletin_040700.html.

U.S. Social Security Administration. 2010. “Amendments to Regulations Regarding Withdrawal of Applications and Voluntary Suspension of Benefits.” Docket No. SSA 2009-0073. Federal Register 75 (235). www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-12-08/pdf/2010-30868.pdf.