Journal of Financial Planning; August 2013

Jon J. Gallo, J.D., chairs the Family Wealth Practice Group of Greenberg Glusker Fields Claman & Machtinger LLP in Los Angeles, California. Together with his wife, Eileen Gallo, Ph.D., he is a founder of the Gallo Institute and the author of two books on children and money. Their website is www.galloconsulting.com.

On June 2, 1897, the New York Journal announced the death of Mark Twain. The announcement came as quite a surprise to Twain, who was alive and well, and resulted in the oft-quoted comment: “The report of my death was an exaggeration.”

Recent reports of the death of the bypass trust at the hands of portability are similarly exaggerated. Prior to enactment of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which made permanent the portability of a deceased spouse’s unused exclusion amount, married couples were faced with a straightforward issue—the estate tax exemption was a use it or lose it proposition. To avoid losing it, estate plans typically provided that the first spouse to die would leave assets equal to his or her exemption to a bypass trust, which would provide the surviving spouse with lifetime benefits but was drafted so that it was not included in the survivor’s taxable estate. In larger estates, the deceased spouse’s assets in excess of the amount left to the bypass trust would be left to a marital trust designed to qualify for the federal estate tax marital deduction.

In some situations, relying on portability offers clear advantages. For example, if the value of the family’s assets is less than twice the exclusion amount, portability offers a way to make use of the deceased spouse’s exclusion amount while obtaining a tax-free step-up in the income tax basis of 100 percent of the family’s assets at the survivor’s death. This step-up is not available for assets held in a bypass trust. Similarly, there may be income tax savings from not having a portion of the income taxed at trust rates.

There are, however, numerous reasons why the bypass trust will continue to be used by many families.

A bypass trust provides protection from the claims of the surviving spouse’s creditors, bankruptcy, and remarriage. It also permits the first spouse to pass away to specify the beneficiaries for whom the bypass trust will be administered following the death of the surviving spouse. In larger estates, a marital trust typically will be combined with a bypass trust to provide these protections during the lifetime of the surviving spouse coupled with the ability to control the disposition of both trusts at the surviving spouse’s death.

Increased Protection Equals Technical Compliance

Unfortunately, this increased protection comes at a cost in terms of technical compliance with an IRS Revenue Procedure that will soon be celebrating its 50th anniversary—Revenue Procedure 64-19. In several recent engagements, it appears that neither the drafting attorney nor the estate’s accountant understood the impact of this Revenue Procedure on the process of actually allocating assets between the bypass trust and the marital trust.

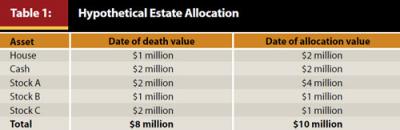

To illustrate the issue, let us look at a hypothetical estate consisting of only five assets—a house, cash, and three stocks. Assume that the decedent passed away in December 2011 when his estate tax exemption was $5 million and that his full exemption was available. In mid-2013 the estate receives an estate tax closing letter, accepting the estate tax return as filed and we are now faced with allocating the assets between the bypass trust and the marital trust. Set forth below is a summary of the assets consisting of a family home, cash, and three stocks. As you will notice in Table 1, the family home doubled in value as did one of the three stocks. The cash and another issue of stock did not change in value, and the third stock fell in value by half.

Estate plans that employ a marital trust/bypass trust arrangement use either a fractional share formula clause or a pecuniary amount formula clause to describe the division of assets between the bypass trust and the marital trust. A fractional share formula clause provides that there is to be allocated to each of the bypass trust and the marital trust a fractional share of every asset in the deceased spouse’s estate.

In this example, as of the date of death, the estate tax exemption was $5 million and the marital deduction would have been $3 million. If a fractional share formula was used, the bypass trust would be entitled to 5/8ths of each and every asset ($5 million/$8 million) available for allocation today, or $6.25 million ($10 million x 5/8th), and the marital trust would receive the remaining 3/8ths ($3 million/$8 million) or $3.75 million ($10 million x 3/8ths) of such assets.

When a fractional share is used, Revenue Procedure 64-19 does not apply and we need not be concerned with the date of allocation values of the assets. We only need to know values as of date of death to determine the fraction of each and every asset that is to be allocated between the bypass and marital trusts. However, easy as they are to describe, fractional share formulas are extremely difficult to administer on an ongoing basis. Each time the trustee sells or distributes a portion of any asset owned in common by both trusts, it becomes necessary to re-determine the percentage interest held by each trust in that asset.

Pecuniary Formula Clause and Revenue Procedure 64-19

Unlike a fractional share clause, a pecuniary formula clause is subject to Revenue Procedure 64-19. A pecuniary share formula identifies a specific amount that is to be allocated to either the bypass trust or the marital trust. The other trust is treated as receiving the residue of the estate.

For example, a pecuniary formula clause might provide that the bypass trust is to be funded with that amount of the deceased spouse’s estate that could pass tax-free as the result of the deceased spouse’s unused exclusion amount, and that the balance of the estate is to be allocated to the marital trust. Applying such a pecuniary formula to the previous example would result in the bypass trust being entitled to receive $5 million (the amount of estate tax exclusion available at date of death). In this example, the $5 million to be allocated to the bypass trust is the pecuniary amount, and all appreciation in the value of the assets in excess of $5 million would belong to the marital trust.

If a pecuniary formula is used, Revenue Procedure 64-19 requires the executor or trustee to satisfy the pecuniary amount in one of two ways: (1) by funding the pecuniary amount using assets valued as of the date of allocation; or (2) by funding the pecuniary amount using date-of-death values but requiring that the assets allocated to the marital trust and the bypass trust are fairly representative of appreciation and depreciation in all assets available for allocation as of the date of allocation. Both of these options mean the estate must incur the cost of updating the appraisals of all assets, and the first option may generate an unexpected income tax liability.

Beware of Income Tax Problems

In our example, an income tax problem exists if the executor decides to allocate assets between the bypass trust and the marital trust using values as of the date of allocation. Satisfaction of the pecuniary amount (whether it is the marital trust or the bypass trust) using assets that have appreciated in value since the date of death will be treated as a sale or exchange between the estate and the trust being funded.

Using the previous example, assume that the estate plan employed a pecuniary amount formula clause that treated the bypass trust as the pecuniary amount. As of the date of death, the pecuniary amount to be allocated to the bypass trust was $5 million. The estate has $3 million of assets that have not appreciated in value between the date of death and today, namely $2 million of cash and $1 million of Stock B. Stock C has fallen in value from $2 million at date of death to $1 million today. This provides $4 million of assets that may be allocated to the bypass trust without recognizing gain. Both the house and Stock A have doubled in value, meaning that allocating $1 million of current value of either asset to the bypass trust will result in recognition of $500,000 of gain. To add insult to injury, IRC Section 267 treats the estate and the bypass trust as related entities and prevents us from offsetting the loss suffered by Stock C against the $500,000 gain.

Alternatively, consider using the fairly representative test. Looking back at our hypothetical estate, we see (1) that the house and Stock A together represented 3/8ths of the total asset value at the date of death, and together they doubled in value as of the date of allocation; (2) that the cash and Stock B together also represented 3/8ths of the total asset value at the date of death, but they remained at that same total value as of the date of allocation; and (3) that Stock C by itself represented the final 1/4th of the total asset value at the date of death, and it dropped to half of that value as of the date of allocation.

To allocate assets fairly representative of appreciation and depreciation as of the date of allocation to fund the $5 million pecuniary bequest to the bypass trust, we would fund 3/8ths of that amount using interests in the house and Stock A (in any proportion we select), another 3/8ths of that amount using cash and Stock B (in any proportion), and the final 1/4th using Stock C.

Trusts that are funded using pecuniary amount formula clauses are far easier to administer because they need not own fractional interests in each and every asset. However, the use of such clauses comes with a potentially significant compliance and tax cost, and failure to comply with Revenue Procedure 64-19 could result in denial of the marital deduction.