Journal of Financial Planning: February 2015

Randy Gardner, J.D., LL.M., CFP®, CPA, is a professor of tax and estate planning at the University of Missouri and a practicing attorney. He is co-author of 101 Tax Saving Ideas and co-founder (with Leslie Daff) of OnlineEstatePlanning.com Inc. Email author HERE.

Leslie Daff, J.D., is a state bar certified specialist in estate planning, trust, and probate law, and founder of Estate Plan Inc. Email author HERE

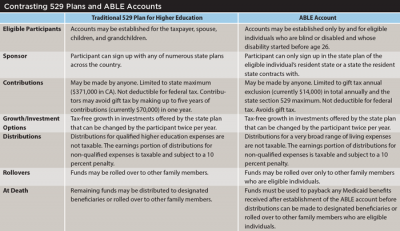

On December 16, 2014, Congress passed the Achieving a Better Life Experience Act of 2013 (ABLE Act) with the strong backing of both political parties and dozens of nonprofit organizations supporting programs for the disabled. The ABLE Act allows an individual, starting in 2015, to establish an ABLE account if they have a disability that started before age 26. Although similar to Section 529 higher education program accounts with regard to the tax benefits provided, ABLE accounts, when established, create a Medicaid lien for Medicaid benefits received after that date.

Understanding ABLE Accounts

An “ABLE account” is an account established by an “eligible individual,” owned by such eligible individual, and maintained under a “qualified ABLE program.”

An eligible individual, also referred to as the designated beneficiary and owner of the account, meets the requirements if, during the taxable year, the individual is entitled to Social Security benefits based on blindness or disability, and such blindness or disability occurred before the date on which the individual attained age 26.

Alternatively, the eligible individual, or the parent or guardian of the individual, may file a disability certification, which is a signed statement by a physician acknowledging that: the individual has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that causes severe functional limitations that can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months, or is blind and such blindness or disability occurred before the individual attained age 26.

A qualified ABLE program is established and maintained by the state in which the eligible individual resides, or another state if the state has a contract with the eligible individual’s resident state.

Although the state can choose whether to start an ABLE program and may establish its own investment limits, the state must operate its program under federal guidelines. These guidelines include: a $14,000 annual limit on non-deductible cash contributions from all contributors to the account; restrictions on excess contributions; one account per eligible individual; separate accounting for each eligible individual’s account; and limiting investment changes by the account holder to twice per year. (Note: the ABLE Act provides for this “twice-per-year change” rule for Section 529 higher education plans, as well.)

Observation: Because of these restrictions, particularly the residency restriction, it is unlikely that states will compete with each other as they do in the Section 529 higher education plan environment.

The ABLE account is exempt from tax; earnings on the contributed amounts grow tax-free. If the contributions and earnings are distributed for qualified expenses, the amounts are not subject to tax. If they are distributed for non-qualified expenses, the pro-rata portion of the earnings attributable to the non-qualified expenses are subject to tax plus a 10 percent penalty. In these respects, ABLE accounts are similar to Section 529 higher education accounts.

One of the differences between 529 and ABLE accounts is the breadth of the qualified expenses. Unlike the qualified expenses of traditional 529 accounts, which are limited to higher education expenses, ABLE account qualified expenses include: education, housing, transportation, employment training and support, assistive technology and personal support services, health, prevention and wellness, financial management and administrative services, legal fees, expenses for oversight and monitoring, and funeral and burial expenses.

Restrictive Environment for Beneficiaries

Many disabled beneficiaries receive public assistance from sources such as Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits. These programs contain numerous restrictions that if violated, could lead to the loss of benefits for the beneficiary. For example, under Medicaid and the SSI program, benefits may be lost if an individual’s assets exceed $2,000, and SSDI benefits may be reduced if the family provides basic support, such as housing and groceries, to the beneficiary.

The ability of disabled individuals to accumulate wealth for future needs is severely impaired. Perhaps the main attraction of the ABLE Act is it allows disabled individuals to accumulate up to $100,000 of assets without the loss of SSI benefits, and up to the state’s Section 529 threshold without losing Medicaid benefits. (For example, California’s Section 529 threshold is $371,000, and New York’s is $375,000). If the $100,000 limit is exceeded, SSI benefits are suspended not terminated; when the account balance falls below $100,000, SSI benefits are restored. Medicaid benefits are not affected.

However, when the eligible individual dies, all amounts remaining in the qualified ABLE account, not in excess of the amount equal to the total medical assistance paid for the eligible individual after the establishment of the account, shall be distributed to the state. In other words, the state is a creditor of (has a lien on) an ABLE account. Any amount remaining after reimbursing the state may be distributed to the eligible individual’s designated beneficiaries. This Medicaid payback requirement is a significant drawback to ABLE accounts and puts them at a significant disadvantage compared to special needs trusts and traditional 529 higher education plans—both of which may also be used to accumulate wealth for disabled children without being considered an available resource to the child.

ABLE Account vs Special Needs Trust

ABLE accounts offer tax benefits and the opportunity to stretch the available resource threshold to $100,000, but special needs trusts can be much more beneficial. Third parties, such as parents or grandparents, can create an irrevocable trust for a special needs dependent. The special needs trust may provide disbursements only for supplemental needs to avoid interfering with Medicaid and SSI benefits, but:

- the trust can be set up for any age beneficiary during life or at the grantor’s death;

- there are no dollar limits on the amounts that can be contributed to or accumulated in the trust;

- there is no Medicaid payback required when the beneficiary passes away; and

- if the special needs trust meets the “qualified disability trust” requirements, up to $14,300 (in 2015) of taxable income may avoid tax.

In conclusion, ABLE accounts are an option for financial advisers to consider when working with families trying to save for a disabled child’s future. Used in conjunction with other tools, such as traditional 529 plans and special needs trusts, ABLE accounts provide a way to save money for a disabled child without interfering with federal and state benefits.

Thanks to Stephen Dale, Esq., LL.M., of Pacheco, California, for his insights and dedication to the needs of the disabled.

Sidebar:

ABLE Account in Action: An Example

Bob is 33 years old. He has Down Syndrome (a disability that started before age 26), and receives a modest income from a job. He also receives Medicaid and SSI benefits, and his parents provide supplemental support. Concerned about Bob’s future, his parents contribute $10,000 and Bob contributes $4,000 to create an ABLE account in 2015. The contributions are not deductible by Bob or his parents, and the parents are not subject to gift tax.

In 2015, the account earns $1,000 of investment income, and Bob uses $3,000 in distributions from the account to pay transportation expenses to and from work. The earnings are not taxable, and the distributions are for qualified expenses, and thus not taxable to Bob. Most importantly, the $12,000 remaining balance in the account does not disqualify Bob for Medicaid or SSI benefits.

After several years, Bob has accumulated $60,000 in his ABLE account ($50,000 of contributions and $10,000 in earnings). He takes a distribution of $6,000 to take a vacation, which is not a qualified expense. Bob is taxed on the $1,000 ($50,000/60,000 x $6,000) earnings portion of the distribution and must pay a 10 percent penalty on the $1,000 of taxable earnings.

Prior to his death, Bob has $90,000 in his ABLE account ($70,000 contributions and $20,000 earnings). He received Medicaid benefits of $40,000 over his lifetime ($30,000 since the establishment of his ABLE account). The ABLE account must repay the State the $30,000 of Medicaid benefits before distributing the remaining balance to Bob’s designated beneficiaries.