Journal of Financial Planning: June 2016

John Burke, CFP®, is the president of Burke Financial Strategies. He has been named one of the top 400 financial advisers by Financial Times for 2015 and 2016. His work has been published in the Journal of Financial Planning and he has also appeared on Fox Business, CNBC, Yahoo! Finance, BNN, and The Street.

Financial planners have a more difficult job in portfolio construction than non-client-facing money management professionals for many reasons. The most obvious one is that clients have a tendency to let their emotions affect their decisions. But intricate technical issues, such as tax management, especially around foreign investments, can challenge financial planners in particular.

Most foreign governments require U.S. brokerage firms to withhold tax on dividends that companies based in their countries pay to U.S. citizens. Through tax treaties, however, individual investors can usually get the tax back if the asset is held in a taxable account—but not if the asset is held in a nontaxable account, like an IRA or a qualified plan.

Astute financial planners should therefore place foreign stocks or foreign stock funds in taxable accounts. There are, however, complications in both getting the tax back and in figuring out which foreign stocks have tax withholding.

Details on Tax Withholding on Foreign Stocks

Most countries tax dividends that their companies pay to foreign investors. This may cause U.S. investors with foreign-based holdings to be taxed twice—once by the foreign country, and once by the U.S. To avoid this double taxation, the U.S. and an array of foreign governments have signed tax treaties.

The following countries have tax treaties with the U.S. that allow for favorable tax treatment of dividends earned by U.S. investors abroad: Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belgium, Canada1, China, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela.

The following countries do not tax company dividends for U.S. investors: Argentina, Bahrain, Columbia, Croatia, Cyprus, Egypt, Estonia, Hong Kong, India, Jordan, Mauritius, Oman, Qatar, Singapore, Slovakia, South Africa, Tunisia, United Kingdom, UAE, and Vietnam.

When taxes are withheld from foreign-stock dividends, U.S. tax rules let you use those taxes as a write-off on your U.S. income tax return. An investor can choose between using the foreign taxes paid as either a tax deduction if you itemize deductions, or a tax credit to reduce your final income tax bill (note: the credit is only applicable when the foreign stocks are held in a taxable account; IRAs and qualified plans are not eligible for this credit). The deduction option reduces your taxable income, while the credit is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in your taxes.

If your taxes on foreign stock dividends are your only foreign taxes paid, and the taxes withheld are less than $300 if filing single or $600 if filing jointly, you can enter the taxes paid directly onto your tax return as a credit. If you do not meet these requirements, a Form 1116 must be completed to claim the credit. The IRS recommends the second method, because it almost always results in lower tax liability.

Some key points related to the foreign tax credit include:

The amount is a credit against any U.S. taxes. Thus, in a situation where foreign taxes are withheld but the taxpayer owes no U.S. taxes, no refund can be claimed. This may not be important for most investors with active employment and a salary, but could be serious for retired investors living on Social Security income.

IRAs and qualified plans are not eligible for this credit, because it only applies to taxable income. Therefore, holding foreign stocks in a retirement account is generally not advisable.

The foreign tax credit cannot be more than the total U.S. tax liability multiplied by a fraction. The fraction is (income from foreign sources) / (total taxable income from U.S. and foreign sources). For example, here is the calculation if one has a total of $1,000 in foreign tax withholding from $5,000 in foreign dividends, and U.S. tax liability is $20,000 on $100,000 of income: $5,000 / $100,000 = 5%; 5% of $20,000 = $1,000.

A taxpayer could claim the entire $1,000 as a tax credit, which is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in taxes, and the tax would become $19,000. In this example, if the tax bill was less than $20,000, one could not get the entire tax credit and would not fully recover the foreign taxes withheld. If the tax bill was $20,000, the taxpayer would get a full recovery of the foreign tax credit—again, if the foreign stocks were not held in an IRA or qualified plan.

The tax rates in the table should be considered the norm for U.S. investors, but the table is a simplification. Belgium, France, and Switzerland have two brackets. In most cases, Swiss securities withhold at a rate of 15 percent with no paperwork requirements for U.S. residents. French securities allow for a 15 percent withholding on individuals, corporations, traditional IRAs, charities, and pension funds, while trusts, banks, partnerships, Roth IRAs, and SEP IRAs are withheld at 30 percent. The French government continues to not recognize a favorable treatment for Roth IRAs and SEP IRAs under their tax laws.

A number of countries, like Germany and Norway, offer a lower withholding rate for individuals but require the investor to certify U.S. tax residency. Germany, for example, has a 26.375 percent rate but also offers a reduced rate of 15 percent. Investors must first file a Form 8802 to have the IRS deliver Form 6166, which is for certification of U.S. tax residency. The user fee to file Form 8802 is $85 and the form is available at IRS.gov. Applicants are advised to request all the 6166 Forms they need (for stocks from multiple countries) on a single Form 8802 to avoid paying more than one user fee. And that form must be given to the investor’s brokerage firm to get the reduced rate.

The details may seem trivial, but the numbers are not. Nestle, for example, is the largest foreign stock trading in the U.S. with a market capitalization of $242 billion. Nestle does not release figures for how much of the company is owned by U.S. investors, but if 30 percent of the company is held by U.S. investors, then $274 million was withheld from dividends and paid to the Swiss government. (See the top 10 largest foreign stocks trading in the U.S. in the table on page 40.)

How Mutual Funds Handle Foreign Tax Withholding

Most U.S. mutual funds that invest in foreign stocks will pass on the foreign tax credit to the shareholders of the given stock. The dividends are reported in Box 1 of IRS Form 1099-DIV, and in Box 6 the foreign tax paid is listed.

Like with foreign tax credits from foreign stocks, one can choose to take the foreign tax amount as a foreign tax credit or as an itemized deduction. The foreign tax credit is almost always a better choice, and it can be reported directly on Form 1040 if the foreign taxes are less than $300 ($600 if married, filing jointly) and if foreign taxes are all reported on 1099s. Otherwise, taxpayers must file Form 1116 to claim the credit.

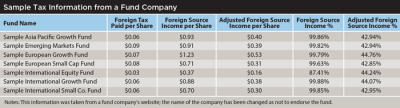

The table above is taken from the website of a fund company. The name of the company was changed in this sample so as not to endorse the fund. The fund company provides this information to investors so they can check their 1099s, which would be issued by the investors’ brokerage firm.

While the brokerage firms handle the withholding on foreign stocks, the mutual funds handle the withholding on foreign stocks in their funds. Both generally rely on information from the transfer agents handling the depository receipts to determine the correct withholding rates for foreign stocks for U.S. investors. The main difference is that with mutual funds, the investor never actually sees the withholding take place in the account. Rather, it is done at the fund level, with the fund passing along a net dividend to investors.

As is the case for foreign stock investors, mutual funds holding foreign stocks should not be held in an IRA or qualified plan. IRA or qualified plan investors who hold funds investing in foreign stocks will not receive a 1099 and will not even know what they missed out on.

Effect on Returns for Individual Investors

Most investors who aim to diversify will end up owning foreign stocks or foreign stock funds. Nestle, Royal Dutch Shell, Siemens, Bayer, Canon, and L’Oreal are all widely recognized stocks, considered by many to be “blue chip,” but they are also foreign stocks that pay dividends and their respective governments require taxes to be withheld.

Investors who hold these issues in an IRA or qualified plan are realizing a lower after-tax return than if they placed them in a taxable account. This is also true if they own these stocks in a mutual fund.

Let’s take a couple of examples to show what can be lost:

Equity portfolio with international holdings. It would not be unusual for an investor to allocate 30 percent of his or her equity holdings to foreign stocks. The U.S. stock market capitalization is approximately 55 percent of the world market capitalization. Most U.S. investors have a home bias, so few have 55 percent of their equity holdings in U.S. stocks and 45 percent in foreign stocks. Therefore, let’s use 30 percent as an example. Further, let’s assume that 75 percent of the 30 percent is in foreign stocks from countries that require withholding and let’s assume an average dividend yield of 3 percent (a reasonable assumption, as foreign stocks pay higher dividends than their U.S. counterparts).

At an average withholding rate of 20 percent, the investor who improperly places their foreign stocks is losing 14 basis points or 0.14 percent of after-tax return, if they can claim the full foreign tax credit.

30%*75%*3%*20% = 0.14%

In an era of low returns, what investor wouldn’t benefit from an extra 14 basis points of return? Income-oriented investors and investors who have a higher allocation to foreign stocks will experience an even greater benefit to placing foreign stocks in their taxable accounts.

Mutual fund portfolio with international holdings. The calculation should be similar for a portfolio constructed with 30 percent in international mutual funds, except that fund investors cannot be sure what their funds will hold throughout the year. Because of portfolio turnover, a mutual fund investor can only guess what their foreign dividends will be until they receive their 1099s. Similar to stock investors, fund investors stand to benefit from placing their international funds in taxable accounts.

Foreign dividend tax withholding differs by each mutual fund depending on the foreign stocks they invest in. It only applies to dividends—not capital gains. Unlike stocks, where an investor can see the foreign withholding as transactions during the year, mutual funds are not as transparent. The foreign tax paid is listed on the 1099 Div under Box 6, and the specific breakdown can be viewed in the “Detail for Dividends and Distributions” that accompany the 1099.

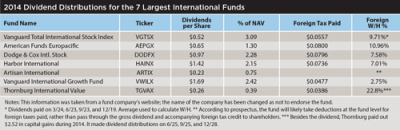

A sampling of the 2014 distributions from the seven largest international funds shows that foreign dividend tax withholding ranges from a low of 2.75 percent for the Vanguard International Growth Fund to a high of 22.8 percent for the Thornburg International Value Fund (see the table above). Some funds, like Artisan International, choose to take deductions at the fund level for foreign taxes paid, rather than pass through the gross dividend and accompanying foreign tax credit to shareholders.

The effect on investors is more clear if we use one of the funds in the table as an example. In 2014, Vanguard Total International Stock Index Fund paid a dividend equal to 3.09 percent of the Net Asset Value (NAV). Of that, 9.71 percent was withheld and sent to foreign governments. It works out to a loss of exactly 0.3 percent for fund investors. Investors who owned the fund in an IRA or qualified pension account were out of luck. On the other hand, investors who held the fund in a taxable account could qualify to get the withholding back in the form of a tax credit as previously explained.

Emerging market investors face the same issue. Once again, investors would be wise to hold these funds in a taxable account.

Investors will not necessarily benefit from placing their foreign stocks or stock funds in their taxable accounts, but it cannot hurt. Taxation on the dividends of foreign stocks for U.S. investors is complicated, but if the investor qualifies for the tax credit and if the investor owns the stocks or stock funds in a taxable account, it does not matter; they will get the full economic benefit of the dividend.

If investors have no choice but to own foreign stocks in an IRA or qualified pension plan, or if they generally do not qualify for the foreign tax credit, they should be aware of the withholding rates of the stocks they are considering or of the foreign tax credit policy of the mutual fund they are buying, as they may be able to reduce the withholding rate.

Endnote

- Canada taxes U.S. investors using cash accounts with Canadian stocks in them and has a tax treaty allowing for a tax credit. Canada, however, does not tax Canadian stocks held by U.S. investors in IRA or qualified accounts.