Journal of Financial Planning: June 2021

Jon Luskin, CFP®, is an author and speaker in San Diego, Calif. He has been recognized as one of the financial planning industry’s top young advisers by InvestmentNews magazine.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

Early life experiences shape your lens of money throughout your life.1 If you grew up in the Great Depression, you thought of the stock market as risky. It’s the opposite for baby boomers. Boomers—who profited from the bull market of the 80s and 90s—had a relatively positive experience with stock market investing.

Millennials have their own distinct lens. They witnessed their boomer parents do well by real estate—at least for the most part. For many millennials, the investment returns on a personal residence are guaranteed (with the occasional bubble thrown in to keep you on your toes).

I recently thought of this millennial real estate investing paradigm when chatting with an old friend. We were talking about personal finance, of course. My friend was convinced that maxing out his 401(k) was completely unnecessary. That’s because he was planning to cash out on his personal residence in retirement, using the proceeds to fund his golden years.

Readers versed in personal finance know that such a plan is problematic. But try explaining that to my buddy. It can be challenging explaining to real estate aficionados that they should be less enamored with the asset class. Yet in this article, I attempt to do just that; I argue (with data from economist Robert Shiller2) that millennials aren’t going to earn the investment returns on their primary residence that their baby boomer parents did.

To begin, we’ll briefly cover the real estate bubble of decades past, examining the link between access to credit and housing prices. Then, we’ll look at the math behind loan terms. We’ll also briefly touch on the significance of dual-income households. With these variables in mind, we’ll examine how more recent housing returns are historically unprecedented, suggesting that future returns are bleak. We’ll wrap up our discussions with what this means for clients and what they can do about it.

The Housing Bubble: Ease of Credit Dictates Prices

In 1998, the real estate bubble began a meteoric rise, accelerated by easy credit. Via the growth of subprime lending, previously ignored consumers were now in the market to buy. With the number of subprime loans quadrupling, demand for housing increased. Housing prices were pushed upward.

The rise in housing prices didn’t last forever. As prices peaked and then declined, access to credit tightened; the number of new subprime mortgages fell. It was a vicious cycle; tight credit accelerated the drop in prices. The decline continued for years.

Eventually, this trend reversed: housing prices bottomed out. Then, prices recovered. Simultaneously, lending standards became more relaxed; credit was once again easier to come by, and thus, more people were in the market to buy.

If the housing bubble has come and gone, why discuss housing prices today? Because arguably, housing prices and access to money were—and continue to be—correlated.

Low Rates Inflate Housing Prices

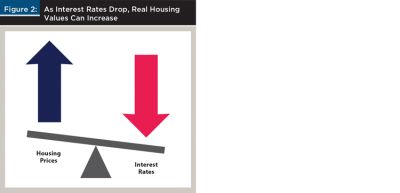

The phenomenon of speculative bubbles aside, easy financing undeniably impacts housing prices. The math behind this is simple: as interest rates drop, the monthly payment for a given mortgage balance decreases. Since homebuyers use affordability (i.e., the size of a mortgage payment) as their yardstick for what house they can afford—lower interest rates mean buyers can afford to purchase more (see Figure 2).

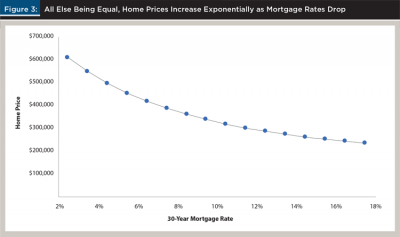

Imagine Joe Smith. Joe is in the market to buy a home. He has $100,000 saved for a down payment. Joe has a monthly budget of $2,000 for mortgage payments. What is the maximum home price that Joe can afford? It depends on the interest rate.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between mortgage rates and housing prices. For a fixed monthly mortgage payment of $2,000 and a $100,000 down payment, interest rates determine how much house one can afford. Looking at the figure, it’s clear that interest rates make all the difference.

Consider what a one percent drop in interest rates does to housing values: a house going for less than half a million dollars—assuming long-term (30-year) mortgage rates are 4.5 percent—is now worth 10 percent more when interest rates drop to 3.5 percent. And, for each successive interest rate drop, housing values increase that much more. The slope is exponential.

Historic Mortgage Rates

Recall Figure 3 showing home prices and interest rates. Notice that a house selling for close to half a million dollars is worth a third as much when long-term mortgage rates were as high as 17.5 percent.

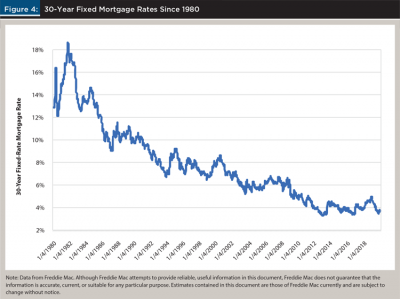

Millennials may scoff at the idea of a 17.5 percent 30-year mortgage rate. Yet, that’s what long-term mortgage rates were when rates peaked in the early 1980s.3 Since then, interest rates have dropped to historic lows.

Small Down Payments Drive Up Housing Prices

Yet housing price inflation doesn’t end with interest rates alone. Down payment requirements also drive housing values, with smaller down payments pushing up housing prices. All else being equal, smaller down payment requirements mean that a household can afford to spend more.

Consider hypothetical homebuyer Sarah Johnson. Unlike Joe, Sarah does not have $100,000 cash for a down payment. Perhaps she can only scrounge together $15,000. So, assuming 30-year mortgage rates of 3 percent, a $500,000 house is out of reach for Sarah because of the usual 20 percent down payment requirements. Yet, were Sarah to secure a lender requiring only 3 percent down, Sarah would now be in the market to buy that $500,000 home.

A long time ago, down payments were as high as 30 percent.4 Today lenders are offering down payments as low as 3 percent.5 With more buyers in the market, demand increases, pushing prices up.

Dual Income Households Drive up Housing Prices

In addition to interest rates and down payment requirements, one final variable influences housing prices: the advent of the dual-income household. In Irrational Exuberance, Robert Shiller writes: “Women joined the workforce in increasing numbers. This increased the availability of credit and home financing. Starting around the 1970s, mortgage lenders began to count the spouse’s income in qualifying a mortgage, expanding available mortgage credit. This helped propel home prices” (page 88).

We’ve now covered how subprime mortgages helped to push up housing prices during the real estate bubble. We’ve also covered the math of interest rates and down payment requirements and how it increases a buyer’s purchasing power. Finally, we touched on how dual-income households impacted increasing housing prices. With this in mind, let’s take a broader look at housing prices over time, examining more than just the real estate bubble of the 2000s.

Shiller on Historic Real Estate Appreciation

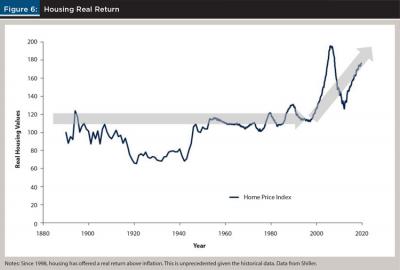

Figure 6 shows housing data from Shiller. From 1890 through 1998, the real return (after inflation) of housing was roughly 0 percent. Zero. That’s the investment return one could expect from buying a house: nothing. Housing kept up with inflation but did little more. What’s more, this calculation ignores the costs of ongoing maintenance.

Then things changed. In 1998, housing returns began their unprecedented rise. Figures peaked around 2006, crashed to a bottom in 2012, and have since rebounded.

And while interest rates began dropping as early as 1982, the slope of interest rates and housing prices means that a buyer’s budget increases exponentially the further interest rates drop. Recall Figure 3.

Of course, other factors can drive housing prices, such as building costs and population. Yet, Shiller notes in Irrational Exuberance that these variables have shown to be “steady and gradual” (population) and “not out of line with long-term trends” (building costs).6 That is, there isn’t compelling evidence that population and building costs are accelerating housing prices.

Expected Investment Returns on Housing

With interest rates and down payment requirements near historic lows and dual-income households increasingly common, what does this mean for future real estate appreciation? It likely means that for investment returns on housing over the last ~20 years to continue into the next 20 years, interest rates and down payment requirements need to keep declining. What’s more, a third income-producing household member is needed to expand a household’s purchasing power further. Short of widespread adoption of polygamy, this last variable is quite unlikely.

Therefore, if you think it’s unlikely that interest rates will decline over the next ~20 years—and if you’re bearish on the popularity of polygamy—then mathematically you think that the investment return we’ve seen in housing will not continue. Further, when interest rates normalize (i.e., increase) and if down payment requirements return to 20 percent, housing depreciation is likely.

Of course, housing prices could continue to grow indefinitely. Long-term mortgage rates could go to zero, or even negative. Down payment requirements could go to zero (again). And polygamy could be the next big thing. These things are possible—just not probable.

Save More Money

Whether the driver is the ease of financing (as I argued) or the speculative mania of crowds (as is argued by Shiller), past outsized real estate appreciation suggests that millennials will not earn the investment returns on their homes that their parents enjoyed. Instead, millennials will likely see their home’s value decrease as a reversion to the mean occurs.

So, for my friend who is betting that future housing values will provide for his retirement, what does this mean? It means that the plan to fund retirement on real estate appreciation likely won’t pan out. So, what should they do?

The solution—of course—is the tried-and-true boring solution when it comes to personal finance: spend less. Save more. It’s not a formula full of financial wizardry, but it certainly gets the job done.

When it comes to spending less, this likely means buying less house. Those living in densely populated areas where housing prices are highest should consider renting instead of buying.

Endnotes

- See cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/abs/aggregate-stability-and-individuallevel-flux-in-mass-belief-systems-the-level-of-analysis-paradox/49CBA021DF4F59475BF9B3BBB0756F9B.

- See econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm.

- See freddiemac.com/pmms/pmms30.html.

- See marketplace.org/2014/10/22/murky-origin-20-percent-down-payment/.

- See knowyouroptions.com/buy-overview/affordable-mortgage-options/3-down-payment-mortgage-for-first-time-homebuyers.

- See Irrational Exuberance: Revised and Expanded Third Edition by Robert J. Schiller.