Journal of Financial Planning: November 2024

NOTE: Please be aware that the audio version, created with Amazon Polly, may contain mispronunciations.

Executive Summary

- We find that innate, fundamental psychological needs such as autonomy, relatedness, and competence explain female financial planners’ happiness with their jobs and desire to stay in their current firms.

- The perceived happiness and attrition of women financial advisers can be influenced by offering female advisers the responsibility for client acquisitions, changing the perception of the meaningfulness of their work, and providing opportunities for self-advocacy.

- At the same time, women can be encouraged to stay with their firms when they are given the responsibility for client acquisition and when they see the firm focusing its efforts on female retention.

Inga Timmerman, Ph.D., CFP®, is an assistant professor of finance at the University of North Florida. Her research explores the state of the financial planning profession. Inga has a Ph.D. in finance from Florida Atlantic University, and she is a former president of the Academy of the Financial Services.

Laura Mattia, Ph.D., CFP®, is the senior vice president and financial adviser at Wealth Enhancement, as well as the host of the Money Matriarchs podcast, where she highlights women who use their financial expertise to make a positive impact. Her commitment to advancing women in financial services is reflected in her university mentoring program and her 2018 book, Gender on Wall Street: Uncovering Opportunities for Women in Financial Services, published by Palgrave Macmillan.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

Females in senior roles in the financial services industry are 20 to 30 percent more likely to leave their firms than females in other industries (Oliver Wyman 2016). This is of particular interest given that males in senior roles in the financial services industry are more likely to stay than males in other industries.1 According to Proudfoot, Corr, Guest, and Dunn (2009), the inability to retain females due to motivational challenges contributes to an employee turnover rate of more than 40 percent a year in the financial services field.

Gender imbalance in the financial advising field has been an issue that major industry and professional organizations like the CFP Board and the Financial Planning Association® (FPA®) have been trying to address for the last two decades. Despite this effort, the number of female CFP® professionals has held steady at around 20–25 percent for over a decade while the newest Cerulli Report (Zulz 2017) calculates that only 16 percent of advisers across all channels are female. Furthermore, as of September 2023, only 1.4 percent of assets under management in the United States were managed by women and people of color (Chiu 2023). In contrast, female clients control more than $5 trillion of investable assets (Krawcheck 2017), and this number is expected to increase as women outlive men. While women have wealth and increasingly accumulate more wealth, much of that wealth is managed by men.

Some of the explanations given for the gender imbalance are the long working hours as well as the culture and barriers of entry associated with the financial advising profession. Adams, Barber, and Odean (2016) point out gender barriers that women have in the profession. Hooker (2019) argues that women are generally not attracted to quantitative professions, that many women are not interested in competitive work environments, and that finance is a profession that disproportionately rewards those who work long and inflexible hours. This, in turn, leads to the inability to achieve work–life balance, especially at the beginning of one’s career when small children may be present. Despite conventional thought predicated on social constructs, Metz (2011) argues that family responsibilities are not the primary reason women leave financial service organizations. Women voluntarily left because of discrimination (including sexual harassment), unsupportive environments, and overall declining job satisfaction. Neck (2015) similarly exposes dissatisfaction causing women to exit senior financial roles, debunking the notion females leave due to work–life balance issues. Neck argues that while family obligations are the often-cited excuse for female underrepresentation in financial services, this is just a red herring that detracts from more complicated explanations. The women interviewed in Neck’s study spoke less about work–life issues and more about unsupportive corporate cultures, barring them from assignments that could develop their skills, give them visibility, or serve as a stepping-stone to promotion.

Based on the research to date, we argue that promoting job satisfaction is critical to retaining female financial planners as financial services firms strive to achieve gender parity. Focusing on job satisfaction, employers can offer tools that can incentivize females to stay in their firms and in the field. In this study, we explore an alternative explanation for the lack of women in financial services.

Financial planning is a subset of financial services, which is a traditionally male occupation. We start from the assumption that women working in the profession hold similar innate needs for job satisfaction as men, yet men may have their innate needs met more often due to social norms and traditional cultures. No prior study has investigated which innate needs motivate female financial planners to determine if they are being satisfied. The purpose of our study is to explore which innate fundamental psychological needs motivate and provide female job satisfaction and how these needs can explain the happiness with the job/profession and the desire to continue working in their respective firms and the field of financial planning. We focus on two main topics: the factors that make women happy/satisfied in their financial services careers and the innate factors that contribute to women staying in their current position and in the profession.

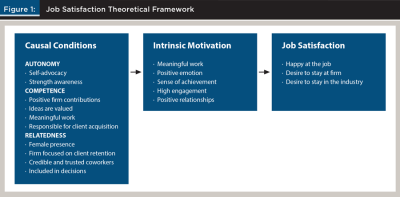

We explore the “female” problem in the financial services industry within the context of positive psychology. We used self-determination theory to assess the factors that contribute to female advisers’ self-perceived happiness and commitment to stay in their job. We incorporate the theory into a framework that accounts for education, demographic characteristics, and the type of firm and pay. Specifically, we investigate the three parts of positive psychology that might explain why women do not stay in their firms and in this profession.

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a human motivation approach to ensuing well-being with strong applications to the workplace (Ryan and Deci 2000). Since the 2000s, psychological research in SDT indicates that intrinsic motivation initiates positive behavior cultivating well-being and happiness in the workplace (Manganelli, Thibault-Landry, Forest, and Carpentier 2018; Martins Nunes, Proenca, and Carozzo-Todaro 2023). Related studies expose negative perceptions of managerial support for basic psychological needs associated with emotional exhaustion, turnover intention, and absenteeism (Williams et al. 2014). Utilizing personal strengths to achieve goals promotes capability (competence) and the ability to influence outcomes (autonomy) at work, two innate needs described in SDT (Gradito Dubort and Forest 2023). Work relationships (relatedness), the third innate need vital to well-being according to SDT, influence how employees utilize their strengths, eliciting job satisfaction (Deci, Olafsen, and Ryan 2017; Williams et al. 2014).

Our study is important to the financial services industry because it provides evidence that financial services executives can learn to satisfy the universal needs of their female employees, thereby fostering increased female job satisfaction. We find that the more a woman belongs in her job/profession, the happier she will be and the more likely she will stay at her firm or in the financial services industry. In line with prior findings from Mattia, Mattia, and Timmerman (2023) and Neck (2015), we find that women leave their jobs and even consider leaving the industry for a combination of professional and personal reasons; one of the main ones is not being valued or appreciated at work.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Job satisfaction has been widely researched as a multidimensional variable prompting how employees feel about their job. Locke (1969) defines the concept of job satisfaction as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences.” Warr (2008) shows that it is derived not from pleasurable experiences but from involvement in worthwhile activities and self-validation. Job satisfaction measurements and theories vary, but, generally, experiencing positive emotions at work is associated with happiness, job satisfaction, and the decision to stay with a firm (Robertson, Birch, and Cooper 2012).

Research on the happiness of employees in the financial services industry can be found in an international context. Among these is a study identifying the attributes influencing how employees in India define a good job (Kumari, Joshi, and Pandey 2014); another similar study involves a U.K. financial firm (Clark 1997). The results show that men are generally more satisfied when compared to women (Kumari, Joshi, and Pandey 2014) and that when financial advisers receive training to reinforce their strengths and skills, it results in greater happiness, increased job satisfaction, and a lower turnover (Clark 1997). Mattia, Mattia, and Timmerman (2023) find no difference in the tools that can be used for motivation and job commitment between genders among financial planners. Proudfoot, Corr, Guest, and Dunn (2009) find a high correlation between positive emotions and job satisfaction and a negative correlation between positive emotions and intention to quit.

Other financial services studies demonstrate that focusing on strengths in one’s job produces a sense of achievement and a positive self-concept, leading to job satisfaction and job retention (Elston and Boniwell 2011). These findings are echoed in a study involving a Netherlands banking organization where employees whose basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness were met; they felt greater value and purpose in their jobs and experienced greater enjoyment overall in their work (Jungert, Van den Broeck, Schreurs, and Osterman 2018).

Relative to job preferences, men and women in most industries are similar, and where differences exist, research claims appear overinflated or driven by gender stereotypes (Hyde 2005). For example, in a meta-analysis exploring gender differences, males are found to value promotion, challenge, and power more than females, while women value relationships and helping others more than males (Konrad, Ritchie Jr., Lieb, and Corrigall 2000). Numerous studies focus on the value women place on supportive colleagues and supervisors, substantiating women’s preference for good relationships (Warr 2008; Clark 2005). Alternatively, more men than women rate autonomy and competence as important (Konrad, Ritchie Jr., Lieb, and Corrigall 2000). These findings are consistent with social constructs rather than innate values. Yet women working in traditionally male occupations, who have not restricted themselves to social norms, have similar preferences as men (Konrad, Ritchie Jr., Lieb, and Corrigall 2000). The attitudes of these non-conforming women validate women to be just as ambitious and committed to their careers as men (Jurik and Halemba 1984). These women, even more than men, emphasize intrinsic preferences for the challenges of their chosen profession, which go beyond salary, job security, and benefits.

SDT in the context of work motivation focuses on psychological needs that are the basis for intrinsic motivation and internalization of job satisfaction (Gagne and Deci 2005). The theory assumes three universal and innate needs must be satisfied to achieve well-being and positive work outcomes: (1) autonomy, (2) competence, and (3) relatedness. These needs are assumed to be universal and required by all to achieve true job satisfaction resulting in engagement and commitment (Ryan and Deci 2000). In research involving work environment experiments, the satisfaction of these fundamental needs yields important work outcomes including job satisfaction and the desire to stay with the organization (Deci et al. 1981).

The concept of autonomy relates to experiencing choice and having agency in one’s actions (Deci et al. 1981). Autonomy support involves the employer understanding and acknowledging the employee’s perspective, offering opportunities for self-initiation (Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, and Leone 1994). Using a longitudinal design and external ratings of job conditions, Grebner et al. (2003) find that feelings of control over one’s work correlates with greater well-being on the job, and job stressors correlate with lower well-being on the job. Studies in two financial organizations show how employees’ perception of management support for their autonomy predicted job satisfaction (Baard, Deci, and Ryan 2004). Job autonomy has also been shown to moderate unhealthy effects of job demands, reducing emotional exhaustion and other burnout dimensions (Fernet, Guay, and Senécal 2004). Work environments that promote or undermine control impact behavior, sense of competence, and overall motivation (Skinner 1995).

The second dimension, competence, refers to feelings of accomplishment and mastery of challenging tasks, and is a strong predictor of motivation and positive outcomes (Gagne and Deci, 2005). Studies show challenging activities increase motivation because employees feel responsible for successful outcomes (Ryan 1982). Competence is not the actual skill but the feeling of effectiveness and a sense of confidence (Deci and Ryan 2002). Positive feedback increases a feeling of competence, motivation, and the desire to seek challenges and increase skills. In an experiment where previously motivated students with perceived competence received negative feedback, their perceived competence and motivation decreased after the feedback (Vallerand and Reid 1984).

Finally, relatedness involves establishing mutual respect, trust, and support with others as fundamental to motivation and well-being (Baumeister and Leary 1995). A study of 221 Swiss career officers revealed a high correlation between belonging to the general staff and work satisfaction (Proyer et al. 2012). Another study of Norwegian elementary and middle school teachers demonstrated a significant correlation between feelings of belonging and job satisfaction and a correlation between the lack of belonging and the motivation to leave (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2011).

These studies demonstrate that creating a work environment that incorporates autonomy, competency, and relatedness leads to increased job satisfaction. Intervention techniques used to teach managers from a major U.S. corporation to support employees by providing non-controlling positive feedback, minimizing controls, supporting autonomy, and acknowledging the subordinate’s perspective and feelings improved work attitudes (Deci, Connell, and Ryan 1989). Although the literature demonstrates evidence of autonomy, competency, and relatedness as universal antecedents to motivation and wellness for both men and women, gender influence on SDT is sparse and reveals inconsistent findings. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness are universal needs of both genders, but each gender experiences these needs differently. A study involving women working in financial services revealed they were less satisfied with autonomy, competency, and relatedness needs than the men at the institution, resulting in less job satisfaction (Baard, Deci, and Ryan 2004). The study showed women perceived their managers as being less autonomy-supportive, they were less satisfied with their relatedness, and received lower performance evaluations. The result is that the women displayed less job satisfaction.

This study explores the extent to which the lack of satisfaction of innate needs related to factors of autonomy, competency, and relatedness explain the low number of women present and retained in the financial advising industry. There might be a way to increase women’s participation and interest in the financial planning profession by creating a work environment in which women feel like they belong and have autonomy. By adding a psychological component to the possible explanations for the lack of gender diversity, we expand the literature and offer an explanation that can change the commitment and presence of women in the profession.

Data and Methodology

We designed and administered a survey of women in the financial planning industry through social media channels like Facebook and LinkedIn. A total of 302 women started the survey. Out of these, 281 completed the survey. The surveys were collected through social media networks/groups for financial advisers. The survey has a total of 75 questions and includes questions about the current (or last) job in the financial services field.2 We collected demographic and educational information, along with data about the type of firm and compensation. Additionally, we collected information about marital status, care of elementary school children, and the percentage of housework done by women to conduct robustness checks and rule out alternative theories.

The questions related to psychological needs are presented as a list of statements to which the women respondents agree/disagree. We asked one to three questions about each of the three dimensions of the self-determination theory. For example, to test autonomy, we asked the respondents to assess if they agree with statements such as “I advocate for myself” or “I am responsible for client acquisition.” To assess the degree of relatedness, we asked the respondents to assess statements like “The firm [I work at] is focused on retaining women” or “I am given equal and interesting opportunities at my firm.” Similarly, to measure competence, we asked the respondents to think of a statement such as “Others seek my input and ideas.”

To code the information, we translated the categorical independent variables as follows: Years in Industry is a code that corresponds with the years worked in the industry, with 1 representing less than one year and 5 representing more than eight years. Relationship is equal to 1 if the respondent is married/coupled and 0 otherwise. Education is equal to 1 if the respondent has a high school diploma, 2 for some college, 3 for a college degree, and 4 for a graduate degree. Income ranges from 1 if the respondent makes less than $50,000 per year to 5 if making more than $250,000 per year. Solo practice is 1 if the respondent is running a solo practice and 0 otherwise. Percent Female>50 represents a 1 if more than 50 percent of the employees at the firm are female (it also includes solo practices) and 0 otherwise. Children is 1 if the respondent has any children of elementary school age and 0 otherwise. CFP is equal to 1 if the respondent holds a CFP® certification and 0 otherwise. CPA or EA is equal to 1 if the participant has a CPA or EA designation and 0 otherwise. The Other Designations variable is equal to 1 if the respondent has any other designation outside of CFP®, CPA, or EA and 0 otherwise. Happiness with Job is measured on a scale of 1–5 where 1 is very unhappy and 5 is very happy. Stay with Firm is equal to 1 if the respondent indicates that she plans to remain in the financial planning firm for the foreseeable future and 0 otherwise. Stay in Profession is 1 if the respondent indicates that she plans to remain in the financial planning industry for the foreseeable future and 0 otherwise. Advocate for Myself ranges from 1 (yes) to 3 (no). Perceived Work is equal to 1 if the respondent believes she works more than a man in the same position and 0 otherwise. Included in Outings is equal to 1 if the perception is that the respondent is included in social events and 0 otherwise. Ideas Overlooked is a 1 if the respondent perceived that her ideas are not taken into consideration and 0 otherwise. Left Out of Decisions is 1 if the respondent perceives she is left out of work-related decisions and 0 otherwise. Responsible for Client Acquisition equals 1 if the respondent is responsible for bringing in new clients and 0 otherwise.

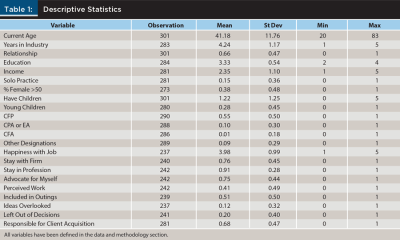

We present the demographic information for the sample in Table 1. The average female adviser respondent is 41 years old and has been in the industry between one and 10 years. Sixty-six percent of respondents are married, and all respondents have somewhere between some college and a graduate degree. Fifty-five percent have a CFP® designation, 10 percent have a CPA or EA designation, and 9 percent have other designations. Only 1 percent have a CFA designation.

Compensation-wise, 47.2 percent are compensated with a salary, 24.5 percent in fees only, 16 percent in commissions or fees and commissions, and 12.4 percent in some other way. For salaries, 22.8 percent of respondents make less than $50,000 per year while 39 percent make more than $100,000 per year. Sole practitioners made up 15.3 percent of respondents, 44.7 percent work in small organizations between two and 14 people, and 25.6 percent in organizations larger than 50 employees. Most respondents, 61.3 percent, work in an RIA environment, 15.4 percent in a broker–dealer environment, and the rest are associated with other types of organizations (for example, banks).

One of the most surprising answers in our sample is the distribution of genders, specifically, who female advisers find themselves working alongside. Ignoring the sole practitioners, 5.49 percent of women work in firms with multiple employees who are 100 percent women, while an additional 15.4 percent work in firms where more than half of the employees are women. By comparison, 35.2 percent of females work in firms where most employees are male. This can be explained by the sample being mostly drawn from the RIA environment. When asked about gender preference in the workplace, 52.3 percent claim to be indifferent between working with men or women, and only 11.5 percent express an explicit preference for working with other women.

The distribution of our construct variables is as follows: 75 percent of respondents believe they advocate for themselves, and 68 percent are responsible for client acquisition. Eighty-eight percent of women believe that the firms they work at (or the last firm worked at before becoming a sole practitioner) focus on retaining women, while 77 percent believe that others in the firms are/were seeking input and ideas. Nevertheless, only 38 percent state that there are other non-administrative staff females in their firms to connect with. Fifty-one percent feel like they are included in social events, like after-work outings. Twelve percent believe that their ideas are overlooked, and 20 percent believe that they are left out of important firm decisions.

The average self-reported happiness level is 3.98 out of 5.00. Seventy-six percent of respondents see themselves staying in their current jobs and 91 percent staying in their profession.

Multivariate Results

We focus on two main factors that measure work satisfaction: (1) self-reported happiness with the job and (2) desire to stay in the job. We present the results in Table 2. In preliminary analysis (not presented here), we verified that the results are not driven by control variables and that the majority of the explanatory power of the model comes from the variables of interest and the variables related to autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

We find no relation between self-reported happiness at work and most of the demographic characteristics such as relationship status, children, or education, including professional designations. We do find a direct relation between the presence of other females in the office and self-reported happiness. Women report they are happier at work when they are surrounded with female coworkers. For the variables of interest, we find that when female advisers advocate for themselves, are responsible for client acquisition in their workplace, and see their work as meaningful and interesting as the work of others, they also report being happier in their position. Additionally, when they perceive their firm to be fostering female retention, they report higher happiness.

In summary, the psychological variables that measure all three types of variables—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—explain about 35 percent of the satisfaction level female advisers experience in their workplace. This number is much higher than found by prior models focused on demographic information or work–life balance.

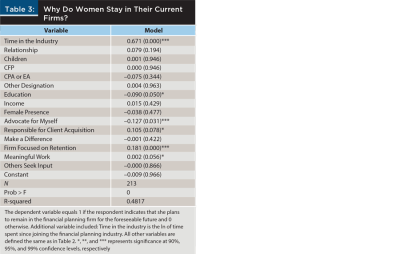

To further decompose the intention of commitment to financial planning, we look at how the individual variables of interest differ between the two dimensions: staying in the current role and staying in financial services. Tables 3 and 4 display the results, respectively. Several variables are associated with the desire to stay in the current firm.

There is a strong direct relation between time spent in the industry and the desire to remain in the same firm. There is also a marginal inverse relation between education and the desire to stay. More education could be translated into more opportunities and, therefore, more employment options outside the current firm. We find that female advisers who consider themselves capable of advocating for themselves are less likely to stay in their job. These results also relate to the positions where women are unhappy. A female adviser who is not happy and who sees herself as able to advocate for herself is most likely to leave and seek a better working environment. But if the women see the firm as trying and focusing on female retention, they are more likely to stay. Marginal results also exist between the willingness to stay and the responsibility for client acquisition, as well as the presence of meaningful work.

We find that being responsible for client acquisition is the strongest predictor of the desire to stay in the current firm. These results do not necessarily contradict the idea that women are not interested in a competitive environment and long working hours. Moreover, they point out that having the autonomy to be responsible for your client acquisition increases the commitment to stay. This is an important result that can be used to increase female adviser retention by financial advising firms. Additionally, women who perceive that their firms are specifically focused on retaining females are also more likely to indicate they are willing to stay with those firms. Focusing on and making it clear that female retention is important to the financial advising firm is a tool that could be used for gender retention. Moreover, it is retention that is focused on client acquisition positions and meaningful work rather than administration positions that matters to female financial advisers.

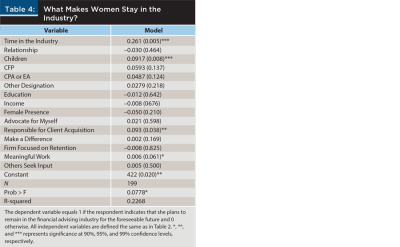

We further look at the results separately by analyzing the factors that are associated with the desire to stay in the industry altogether.

Once again, there is a strong association between the time already spent in the industry and the desire to stay. This is not surprising, as many years in, there is expertise and a career that is perhaps hard to give up. There is the potential for survivor bias (we only survey women who are still in the profession), but the bias is alleviated by the sample, which includes women from their first year in the industry. Additionally, in preliminary analysis, designations like the CPA/EA or other types of non-CFP® designations contribute to the desire to stay. Again, there is an entrenchment that comes with extra designations; women who are on the fence about staying in a field most likely do not pursue additional designations. The designation significance disappears when we add additional variables, which may indicate that it is a proxy for the length of time spent in the industry.

When isolated, the self-determination characteristics associated with the desire to stay in the industry are responsible for client acquisition and the feeling of meaningful work. Women who are responsible for client acquisition and who derive the feeling that their work is meaningful are more likely to indicate that they are planning to stay in the financial advising industry for the foreseeable future. We find that the longer the time in the industry, the more meaningful the work perceived, and the greater the responsibility for client acquisitions, the more likely the women respondents are to see themselves in the same industry in the foreseeable future (in other words, they are not planning to leave the industry). The presence of young children is also positively associated with the desire to stay in the industry. Although initially surprising, the results may hint at the efficiency that is required to work and balance the care of small children, which in turn focuses the female adviser on engaging with the profession in the most satisfying way possible. This also points out that the work–life balance argument may not necessarily apply to this industry.

Next, to further expand our understanding of why women decide to stay or leave other firms, we incorporate the social and integrative aspects of belonging to the firm with questions such as “I feel included in work events” and “I feel included in social events” as well as the perceived effort women put in their jobs compared to men. Table 5 presents the results. Model 1 introduced alternative explanations to the desire to stay in the firm, and Model 2 brings back the variables that represent autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as found in previous results.

Women who view their work to be harder than equivalent work for the men at the same firm are less likely to indicate they are willing to stay in their current positions. Similarly, when women feel they are left out of firm decisions, they are less likely to want to stay in their roles. Conversely, there is a slight indication that women who see their coworkers as trustworthy and credible are more likely to want to stay in their jobs. However, when we reintroduce the variables of interest we found to be significant earlier in the study, specifically responsibility for client acquisitions and focus on female retention, we observe that most of the prior relationships have been absorbed into variables that represent autonomy, competence, and relatedness. This is an important finding that documents self-determination variables have a strong influence on the willingness and plan of female financial advisers to stay in their firms. These are the primarily explanatory variables for why women stay or leave their firms and the industry, rather than social and cultural explanations.

We conclude that in addition to the perception of one’s work as being meaningful, which still holds, the variables that influence and relate to the determination to stay or leave are psychological. Women who feel that they are working more compared to men are less likely to stay in their firms. Women who are responsible for client acquisition and have the perception that their firms are specifically focused on gender retention are more willing to stay in their jobs. This is the first time that we are aware that these findings are documented in the literature for financial advisers.

Conclusion and Implications

Using self-determination theory and focusing on the psychological needs of female financial advisers, we find that the happiness with a financial advising job and the desire to stay in that job, and the profession, is driven by several factors that have not been explored. The presence of other women in non-administrative roles and the perception that the firm fosters female retention have a strong positive association with the perceived happiness in the job. Intrinsic need satisfaction for autonomy, competence, and relatedness provides a framework for empirical exploration of job satisfaction for females in the financial services field. These variables explain much more of the variation in happiness with the job and desire to stay in the job, and within the profession in general, than demographic characteristics alone. Overall, we can enhance the working environment for women financial advisers by teaching them how to advocate for themselves, making them responsible for client acquisition, increasing the perception of the meaningfulness of their work, and focusing firm efforts on explicit female retention. The happiness with a position can increase as the number of females in non-administrative roles increases. Although this may be a slow process, these factors are associated with the self-reported happiness of female financial advisers in the United States.

Using a few alternative specifications, we always find the same results: the more value women feel in their jobs, the more important they feel their role is, and the more they feel like part of the team (both socially and professionally), the happier they are and the less willing they are to quit their roles and leave the profession.

To incentivize women to stay with their firms, employers can, once again, offer the opportunity for women to directly be responsible for client acquisition and increase the explicit retention efforts of the firm. Although other factors are also associated with the propensity of staying/leaving the same job, such as time in the industry and education, firms have less control over those factors. Instead, they can focus on the efforts that may directly promote an environment in which women feel they have autonomy, competence, and can relate to their colleagues and firms.

Finally, some factors can also be honed to keep women in the financial planning profession. Leadership training to help women develop goals and identify strengths could help build employee autonomy. Encouraging women to participate in firm decisions, the client acquisition process, and meaningful work can help them feel more competent. By employing effective team building to engender credible and trustworthy teams, a firm can demonstrate its commitment to retaining all (particularly female) employees and create a feeling of relatedness and belonging. These initiatives could help women find meaning in their jobs and keep them in the industry and retain them at a firm.

When firms keep in mind the needs of their financial planners, they can provide environments that address the needs leading toward job satisfaction and other positive work outcomes including overall performance and retention. In the end, it is not the work–life balance, the math orientation of the profession, or the possibility of a promotion that matters. It’s the autonomy to make decisions, the competence they feel they have, appreciation, and the relatedness with the job and colleagues that matter.

Citation

Timmerman, Inga, and Laura Mattia. 2024. “Why Are There So Few Women in the Financial Services Industry?” Journal of Financial Planning 37 (11): 70–84.

Endnotes

- See www.oliverwyman.com/our-expertise/insights/2016/jun/women-in-financial-services-2016.html.

- Not all participants see all questions. The questions are adaptive to prior answers. A copy of the survey is available upon request.

References

Adams, R. B., B. M. Barber, T. and Odean. 2016. “Family, Values, and Women in Finance.” Retrieved from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2827952 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2827952.

Baard, P. P., E. L. Deci, and R. M. Ryan. 2004. “Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis of Performance and Well-being in Two Work Settings.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34 (10): 2045–2068.

Baumeister, R. and M. R. Leary. 1995. “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin 117: 497–529.

Clark, A. E. 1997. “Job Satisfaction and Gender: Why Are Women So Happy at Work?” Labor Economics 4 (4): 341–372.

Clark, A. 2005. “What Makes a Good Job? Evidence from OECD Countries.” In Job Quality and Employer Behavior. Palgrave Macmillan: United Kingdom: 11–30.

Chiu, B. 2023, November 16. “Outperforming Female Fund Managers Still Struggle to Access Capital.” Forbes. www.forbes.com/sites/bonniechiu/2023/11/02/outperforming-female-fund-managers-still-struggle-to-access-capital/.

Deci, E. L., G. Betley, J. Kahle, L. Abrams, and J. Porac. 1981. “When Trying to Win: Competition and Intrinsic Motivation.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 7 (1): 79–83.

Deci, E. L., J. P. Connell, and R. M. Ryan. 1989. “Self-determination in a Work Organization.” Journal of Applied Psychology 74 (4): 580.

Deci, E. L., H. Eghrari, B. C. Patrick, and D. R. Leone. 1994. “Facilitating Internalization: The Self-determination Theory Perspective.” Journal of Personality 62 (1): 119–142.

Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2002. “Overview of Self-determination Theory: An Organismic Dialectical Perspective.” Handbook of Self-determination Research: 3–33.

Deci, E., A. Olafsen, and R. Ryan. 2017. “Self-determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 4: 19–43.

Elston, F., and I. Boniwell. 2011. “A Grounded Theory Study of the Value Derived by Women in Financial Services through a Coaching Intervention to Help Them Identify Their Strengths and Practice Using Them in the Workplace.” International Coaching Psychology Review 6 (1): 16–32.

Fernet, C., F. Guay, and C. Senécal. 2004. “Adjusting to Job Demands: The Role of Work Self-Determination and Job Control in Predicting Burnout.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 65 (1): 39–56.

Gagne, M., and E. L Deci. 2005. “Self-determination Theory and Work Motivation.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 26 (4): 331–362.

Gradito Dubort, M-A., and J. Forest. 2023. “Focusing on Strengths or Weaknesses? Using Self-Determination Theory to Explain Why a Strengths-based Approach Has More Impact on Optimal Functioning Than Deficit Correction.” International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 8: 87–113.

Grebner, S., N. Semmer, L. L. Faso, S. Gut, W. Kälin, and A. Elfering, A. 2003. “Working Conditions, Well-Being, and Job-Related Attitudes among Call Centre Agents.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 12 (4): 341–365.

Hooker, B. 2019. A. Lusardi interview of Dr. B. Barber. UC Davis Graduate School of Management. Retrieved from https://gsm.ucdavis.edu/post/why-so-few-women-finance.

Hyde, J. S. 2005. “The Gender Similarities Hypothesis.” American Psychologist 60 (6): 581.

Jungert, T., A. Van den Broeck, B. Schreurs, and U. Osterman. 2018. “How Colleagues Can Support Each Other’s Needs and Motivation: An Intervention on Employee Work Motivation.” Applied Psychology 67 (1): 3–29.

Jurik, N. C., and G. J. Halemba. 1984. “Gender, Working Conditions and the Job Satisfaction of Women in a Non-Traditional Occupation: Female Correctional Officers in Men’s Prisons.” The Sociological Quarterly 25 (4): 551–566.

Konrad, A. M., J. E. Ritchie Jr., P. Lieb, and E. Corrigall. 2000. “Sex Differences and Similarities in Job Attribute Preferences: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 126: 593–641.

Krawcheck, S. 2017. “The Future of Business.” CNBC. www.cnbc.com/the-future-of-business-sallie-krawcheck/.

Kumari, G., G. Joshi, and K. M. Pandey. 2014. “Analysis of Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of the Employees in Public and Private Sector.” International Journal of Trends in Economics Management & Technology 3 (1).

Locke, Edwin A. 1969. “What Is Job Satisfaction?” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 4 (4): 309–36. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(69)90013-0.

Mattia, M., L. Mattia, and I. Timmerman. 2023. “Why do Wealth Advisors Stay or Leave Their Firms?” Financial Planning Review 7 (1).

Manganelli, L., A. Thibault-Landry, J. Forest, and J. Carpentier. 2018. “Self-Determination Theory Can Help You Generate Performance and Well-Being in the Workplace: A Review of the Literature.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 20 (2): 227–240.

Martins Nunes, P., T. Proenca, and M. Carozzo-Todaro. 2023. “A Systematic Review on Well-Being and Ill-Being in Working Contexts: Contributions of Self-Determination Theory.” Personnel Review 53 (2): 376–408.

Metz, I. 2011. “Women Leave Work Because of Family Responsibilities: Fact or Fiction?” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 49 (3): 285–307.

Neck, C. 2015. “Disappearing Women: Why Do Women Leave Senior Roles in Finance? Further Evidence.” Australian Journal of Management 40 (3): 511–537.

Proyer, R. T., H. Annen, N. Eggimann, A. Schneider, and W. Ruch. 2012. “Assessing the “Good Life” in a Military Context: How Does Life and Work Satisfaction Relate to Orientations to Happiness and Career Success among Swiss Professional Officers?” Social Indicators Research 106 (3): 577–590.

Proudfoot, J. G., P. J. Corr, D. E. Guest, and G. Dunn. 2009. “Cognitive-Behavioral Training to Change Attributional Style Improves Employee Well-Being, Job Satisfaction, Productivity, and Turnover.” Personality and Individual Differences 46 (2): 147–153.

Robertson, I. T., A. Jansen Birch, and C. L. Cooper. 2012. “Job and Work Attitudes, Engagement and Employee Performance: Where Does Psychological Well-Being Fit In?” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 33 (3): 224–232.

Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68.

Ryan, R. M. 1982. “Control and Information in the Intrapersonal Sphere: An Extension of Cognitive Evaluation Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 43 (3): 450.

Skaalvik, E. M., and S. Skaalvik. 2011. “Teacher Job Satisfaction and Motivation to Leave the Teaching Profession: Relations with School Context, Feeling of Belonging, and Emotional Exhaustion.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (6): 1029–1038.

Skinner, E. A. 1995. Perceived Control, Motivation, & Coping. Volume 8. Sage.

Vallerand, R. J., and G. Reid. 1984. “On the Causal Effects of Perceived Competence on Intrinsic Motivation: A Test of Cognitive Evaluation Theory.” Journal of Sport Psychology 6: 94–102.

Warr, P. 2008. “Work Values: Some Demographic and Cultural Correlates.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 81 (4): 751–775.

Oliver Wyman. 2016. “Women in Financial Services: Time to Address the Mid-career Conflict.” www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/global/en/2016/june/WiFS/WiFS_2016.pdf.

Williams, G., H. Halary, C. Niemiec, O. Sorebo, A. Olafsen, and C. Westbye. 2014. “Managerial Support for Basic Psychological Needs, Somatic Symptom Burden and Work-Related Correlates: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” Work and Stress 28 (4): 404–419.

Zulz, E. 2017, January 18. “Only 16% of Advisors Are Women: Cerulli.” ThinkAdvisor. www.thinkadvisor.com/2017/01/18/only-16-of-advisors-are-women-cerulli.