Journal of Financial Planning: February 2011

Jeff Whitworth, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of finance in the School of Business at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. He teaches in the areas of corporate finance and investments.

Joseph McCormack, Ph.D., CFA, is an associate professor of finance in the School of Business at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. He teaches in the areas of corporate finance and international finance.

Executive Summary

- This paper presents a tax-efficient stock investing strategy whereby investors who regularly contribute to charity can earn after-tax returns that on average exceed their pre-tax returns. This is accomplished by realizing tax losses on stocks that have declined, while simultaneously using appreciated stocks in lieu of cash to make planned charitable donations.

- Expected returns can be increased further by using more volatile stocks to implement this strategy. Risk can be controlled by diversifying across multiple stocks. Diversification does not reduce the strategy’s tax benefits because accrued gains on donated stocks are never realized and therefore are not offset against capital losses.

- The improvement in after-tax returns may be smaller if the investor has some long-term gains in the same year, if the stock incurs a loss exceeding $3,000, and/or if the stock’s value grows to an amount larger than the planned charitable donation. Even in these cases, however, the investor’s expected return will be higher as a result of implementing this tax-efficient stock investing strategy.

One of the most important services financial planners and tax accountants provide is to help clients understand and comply with the tax laws while minimizing the adverse effect of taxation on their investments. Because taxes can significantly reduce the effective returns on a portfolio, good planning in this area is essential. Tax planning is also important for the many individuals who regularly donate to charitable organizations. While the motive for giving is normally philanthropic, it is always a good idea to make the most tax-efficient gift possible, assuming all other factors are equal. Most contributions are made in cash, but a donor can alternatively give stocks, bonds, or other assets to a charity, and in many cases one method of donation can result in a greater tax benefit than another.

The purpose of this article is to present a simple but effective stock investment strategy for individuals who regularly make charitable donations. We illustrate via a series of examples that a stock’s expected after-tax return is increased when the possibility exists that it might be used as part of a planned charitable donation. We then discuss ways investors can increase their returns by maximizing the tax benefits of this strategy, while simultaneously limiting risk. Finally, we discuss potential limitations on the strategy’s effectiveness.

Exploiting the Asymmetric Taxation of Gains and Losses

It has long been recognized that stock investors have a “tax-timing” option (Constantinides 1983, 1984). Stockholders can sell shares that have gone down in value to take advantage of the capital loss deduction. Losses are netted first against any gains realized that year, and then against up to $3,000 of ordinary income. Tax-savvy investors can also delay the sale of appreciated stocks, at least until the investment has been held for one year, thereby qualifying for the lower long-term capital gains tax rate.

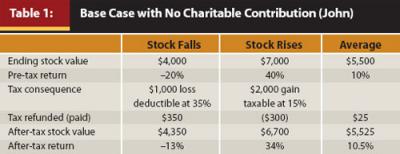

To illustrate this, consider the following example. Suppose that John, a client in the 35 percent income-tax bracket, invests $5,000 in a stock today. For simplicity, assume that after one year the stock will be worth either $4,000 or $7,000 with equal probability, at which time the position will be liquidated and the proceeds invested in another stock. Before taxes, the stock has an expected return of 10 percent, given that its average payoff is ($4,000 + $7,000) / 2 = $5,500. However, John can actually achieve an expected after-tax return higher than 10 percent, as shown in Table 1. If the stock’s value declines to $4,000, he can deduct a loss of $1,000 against ordinary income, resulting in a tax savings of 0.35 × $1,000 = $350 and a net after-tax loss of only $650. On the other hand, if the stock’s value rises to $7,000, John can sell just after the one-year holding period requirement is met, realizing a long-term gain of $2,000. Under current law, he will owe taxes of 0.15 × $2,000 = $300, resulting in a net after-tax gain of $1,700. His expected after-tax profit on the investment is therefore ($1,700 – $650) / 2 = $525, or 10.5 percent of the original investment. As this example demonstrates, exploiting the differential tax treatment of short-term losses and long-term gains can improve an investor’s expected return.

Combining Tax-Loss Selling with the Use of Appreciated Stocks for Charitable Donations

For those who regularly make charitable contributions, the tax code provides a means to pay even less in capital gains taxes. In lieu of donating cash, a person may donate appreciated stock or mutual fund shares (presumably with value comparable to the planned cash donation). If the shares have been held for at least one year, the donor realizes a double benefit: (1) the capital gain is excluded from the donor’s taxable income, so no capital gains taxes are paid, and (2) the donor is allowed to deduct the full market value of the shares—including both the original basis and the gain—against ordinary income, even though the gain was never included as part of his or her gross income.

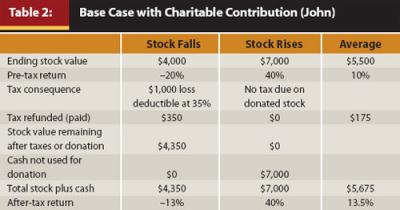

To better understand this, suppose that John has made a $10,000 pledge to his favorite charity, with the actual donation to occur one year from now. John knows that he will have enough cash (separate from his investments) to fulfill his pledge, so the donation is certain to occur. However, if the value of John’s stock rises to $7,000, he can use the appreciated shares plus $3,000 cash to make his planned $10,000 donation. The tax deduction for his charitable contribution is unaffected by the method of donation, and neither John nor the charity incurs a capital gains tax liability. After making his donation ($7,000 in appreciated stock plus $3,000 cash), John now has $7,000 in additional cash remaining that he had planned to donate but is now available to be invested. Since there are no further taxes due on this $7,000, he has effectively realized a tax-free gain of $2,000. Of course, if the stock had fallen to $4,000, John still could have sold the shares, deducted the $1,000 loss (realizing an after-tax loss of $650), and contributed the $10,000 in cash as planned. In this case, he would not use the $4,000 in depreciated shares as part of his donation because he would not be able to deduct the $1,000 capital loss. The expected after-tax profit using this strategy is effectively ($2,000 – $650) / 2 = $675, or 13.5 percent. (See Table 2.)

Reichenstein (2007) notes that a stockholder’s effective return is equal to the pre-tax return when the stock will be donated to charity (making the gains tax-exempt), but less than the pre-tax return when the capital gains will be subject to taxation. In view of this, it seems impossible at first that John’s average after-tax return could exceed his average pre-tax return. This surprising result occurs because capital gains and losses are taxed asymmetrically. Although he cannot predict in advance whether the stock will rise or fall, John can dispose of it after the fact in the manner that creates the greatest tax benefit or the smallest tax liability. Capital losses can be offset against ordinary income (which would have been taxed at 35 percent), while capital gains are taxed at only 15 percent if the asset is sold after one year or zero percent if it is donated to charity.

For charitable contributions, it is important to realize that the preceding analysis is valid only if the donation is treated as a “sunk cost.” In other words, John is fully prepared to make the contribution with cash, but substituting appreciated shares simply results in a further tax benefit. The incremental benefit of this strategy would be reduced or eliminated if John had planned to donate less (or not at all) should the stock investment not perform well. Related to this point, note that in our calculations above, we did not consider the $3,500 reduction in taxes due to John’s $10,000 charitable donation, because this occurs whether the contribution is made with cash, stock, or some combination of the two. Note also that the charity is indifferent to the method of donation; it receives $10,000 and pays no taxes in either case.

The Positive Effect of Volatility on After-Tax Returns

So far, we have shown that investors who regularly make charitable contributions can achieve expected after-tax returns greater than their pre-tax returns using standard taxable investment accounts. This occurs because of the asymmetric tax treatment of gains and losses. In this context, the fact that an investment’s value rises in some periods while falling in others is beneficial. In fact, the strategy is actually more effective when the investor chooses higher-volatility stocks.

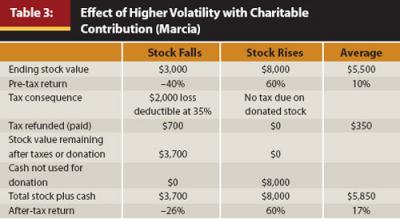

To illustrate this, suppose that Marcia is in a situation identical to that of John described in the previous section, except that she invests her $5,000 in stock that will rise to $8,000 or fall to $3,000, with equal probability. The expected pre-tax return on this investment is still 10 percent as before, given that its average payoff is ($8,000 + $3,000) / 2 = $5,500. However, this stock is clearly more volatile than John’s, because the potential gain or loss is greater.

While investors usually prefer to avoid higher volatility, in this case it creates an important tax benefit. As shown in Table 3, if the stock falls to $3,000, Marcia will recognize a $2,000 loss, resulting in a tax savings of 0.35 × $2,000 = $700. Her after-tax loss will therefore be $2,000 – $700 = $1,300. On the other hand, if the stock rises to $8,000, Marcia can use it (along with $2,000 cash) to make her planned $10,000 donation. This would leave her with $8,000 cash remaining and no taxes due—a gain of $3,000. Therefore, Marcia’s expected after-tax profit would be ($3,000 – $1,300) / 2 = $850. This represents a return of 17 percent, which is superior to John’s expected return of 13.5 percent.

Getting the Best of Both Worlds by Diversifying

As noted, volatility enhances the outcome of our tax-based strategy. The preceding example illustrates that, holding the pre-tax expected return constant, a more volatile stock has a higher after-tax expected return. This is consistent with prior findings (Constantinides 1983, 1984; Dammon et al. 1989) that volatility affects an investor’s optimal trading strategy and the value of the tax-timing option. In spite of this, investors still may be reluctant to take on higher-volatility stocks because of the added risk. This is understandable. Fortunately, there is a way to reduce this risk without sacrificing the higher expected after-tax return.

In the example above, Marcia invested $5,000 in a single stock that would be worth either $3,000 or $8,000 after one year. However, she could have made several smaller investments in stocks with similar risk-return profiles. It is not likely that all of the stocks will rise or fall simultaneously. A more probable scenario involves some of the stocks experiencing gains while others suffer losses. In such cases, Marcia could strategically sell all stocks that have declined in value while using those that have increased for her pre-planned charitable contribution. No long-term capital gains are actually realized for tax purposes, so the fact that some stocks have risen in value does not reduce the deduction from tax-loss selling. Thus, Marcia is able to take advantage of both tax benefits simultaneously. In the end, diversification does not affect her expected after-tax return, but it reduces her risk because of the portfolio effect.

To demonstrate this, suppose Marcia divides her $5,000 investment equally between two stocks. Each investment of $2,500 is equally likely to be worth $1,500 or $4,000 at the end of the year. To simplify the analysis, we will assume that the returns of these two stocks are independent.1 In this situation, there is a 25 percent probability that both stocks will fall in value. This outcome is identical to that of a $5,000 investment that declines to $3,000; as previously shown, the after-tax loss is $1,300. There is also a 25 percent probability that both stocks will rise, resulting in a tax-free gain of $3,000 when the shares are used for Marcia’s planned charitable donation. However, there is a 50 percent chance that one stock will rise to $4,000 while the other falls to $1,500. In this case, the first stock could be substituted for part of her planned cash donation, while the second stock is sold to realize a deductible loss. The first stock’s $1,500 gain is tax-free because the asset is donated to charity, while the second stock’s $1,000 loss is reduced to only $650 after taxes. The net result for this outcome is an after-tax gain of $1,500 – $650 = $850.

Considering the three possible outcomes, the expected after-tax profit is (–$1,300 × 0.25) + ($3,000 × 0.25) + ($850 × 0.50) = $850, which is still a return of 17 percent. This is the same average outcome Marcia would have if she invested all $5,000 in a single stock. However, her standard deviation is only 30.4 percent with the two-stock portfolio, compared to 43 percent investing in the single stock. While this risk reduction is certainly beneficial, it is important to note that Marcia could achieve even lower levels of risk by diversifying across a larger number of securities.

Potential Limitations to the Strategy

At this point, a word of caution is in order given the complexities of how capital gains and losses are taxed. Short-term losses are deducted first against short-term gains realized in the same tax year, then against long-term gains in that year, and finally against up to $3,000 of ordinary income. If the investor already has a significant amount of short-term gains, our strategy’s effectiveness is not reduced because any losses would offset these gains (which would have been taxed at the full ordinary rate). Likewise, if the investor has no realized gains (short-term or long-term) and if the loss is unlikely to exceed $3,000, our strategy is fully effective because the entire loss could be deducted against ordinary income. However, after-tax returns from our strategy will be lower if: (1) the investor has realized little or no short-term gains but a significant amount of long-term gains, (2) the potential short-term capital loss (minus any realized gains from the same year) exceeds $3,000, or (3) the stock’s value may grow to an amount larger than the planned donation.

To better understand these limitations, suppose Steve invests $5,000 in stock that is equally likely to be worth $4,000 or $7,000 in one year. If the securities increase in value to $7,000, he can use the appreciated shares for a pre-planned charitable donation, making the entire $2,000 gain tax-free. So far, this situation is identical to that of John illustrated in Table 2. However, assume further that Steve has no short-term gains this year but has already realized a sizeable long-term gain on a different investment, which is taxable at 15 percent. If the new stock’s value declines to $4,000, the loss of $1,000 is offset not against ordinary income but instead against the long-term capital gain. As shown in Table 4, this results in a tax savings of only 0.15 × $1,000 = $150 and an after-tax loss of $850. Therefore, Steve’s expected after-tax profit would be ($2,000 – $850) / 2 = $575, a return of 11.5 percent. Note that even though this is a reduction from John’s 13.5 percent average return, it still exceeds the investment’s pre-tax return of 10 percent. Therefore, our strategy still increases the investor’s expected after-tax return (albeit to a lesser extent), even when other long-term gains have been realized.

Another potential problem is the $3,000 limitation on capital loss deductions against ordinary income. To see what effect this might have, suppose that Katie is in a situation comparable to John’s, but with larger investments and planned donations. Specifically, Katie plans to make a $35,000 charitable contribution in one year, and she invests $25,000 today in shares that may be worth either $35,000 or $20,000 with equal probability. If the investment rises in value to $35,000, Katie can use it for her charitable donation and therefore enjoy a tax-free $10,000 gain. However, if her investment falls to $20,000, she incurs a $5,000 pre-tax loss. In the event that she has realized no offsetting gains, she may deduct only $3,000 of this loss against ordinary income, for a tax benefit of 0.35 × $3,000 = $1,050. Therefore, her after-tax loss would be $3,950. Averaging both cases, we see that her expected after-tax profit is ($10,000 – $3,950) / 2 = $3,025, a return of 12.1 percent. (See Table 5.)

Obviously, this is less than John’s 13.5 percent return because Katie is unable to deduct all of her potential capital loss. However, 12.1 percent is still greater than the investment’s assumed 10 percent average pre-tax return. In reality, Katie’s effective return may be considerably higher than 12.1 percent because the unused portion of her capital loss deduction can be carried forward to offset gains or ordinary income in future years. Even in the extremely unlikely case where she has no future gains or ordinary income to offset, Katie’s expected after-tax return will still be greater than her pre-tax return because: (1) she can still deduct part of her loss, and (2) she is taxed on none of her gains so long as the value of her appreciated stock does not exceed her planned donation.

The size of the investor’s planned charitable donation can have a dramatic impact on his after-tax return. Suppose that Larry, like John, invests $5,000 today in securities that may rise to $7,000 or fall to $4,000. However, Larry is planning to donate only $1,000, a considerably smaller amount. If his $5,000 investment falls to $4,000, Larry still should sell the securities, realize the full capital loss deduction, and make his planned cash donation as usual, resulting in an after-tax loss of $650. However, if his investment’s value rises to $7,000, not all of the gain is tax-free. Assume that Larry uses $1,000 of his appreciated stock to make his planned donation and sells the remaining $6,000 just after meeting the one-year holding-period requirement. The gain on the $6,000 in securities is taxable at the long-term rate of 15 percent, but the basis is not the full $5,000 originally invested. Because 1/7 of the shares were given to charity, the basis is now $5,000 × (1 – 1/7) = $4,285.71. Therefore, Larry’s taxable gain is $6,000 – $4,285.71 = $1,714.29, which creates a tax liability of $257.14. The amount of cash left is $6,742.86, including the $6,000 from the stock sale, minus $257.14 paid in capital gains taxes, plus the $1,000 cash that otherwise would have been donated. The after-tax gain is therefore $1,742.86. Considering both cases, Larry’s average after-tax profit is ($1,742.86 – $650) / 2 = $546.43. This represents a return of 10.93 percent. (See Table 6.)

Conclusions and Recommendations

Tax-efficient investing requires careful planning, and this is one area where advisers and accountants can help their clients retain as much wealth as possible in their portfolios by minimizing the amount lost to taxes.

In this article, we illustrate a simple strategy for investors who regularly donate part of their income to charity. A client has the opportunity to deduct a capital loss if it occurs, or to donate an appreciated stock in lieu of cash, effectively enjoying its entire gain tax-free. Employing this strategy can boost average after-tax returns without a corresponding increase in risk. Ideally, the stocks chosen should be among the more volatile assets in the investor’s overall portfolio. To reduce risk, it is also helpful to select multiple stocks that are not highly correlated with each other.

It is important to note that there are limits to how much the strategy can boost after-tax returns. Returns may be moderated somewhat if short-term losses are offset against more lightly taxed long-term gains, if capital losses exceed the $3,000 maximum that can be deducted against ordinary income, or if the value of the stock grows larger than the planned contribution. Nevertheless, these obstacles do not eliminate the advantage of combining tax-loss selling with the use of appreciated stocks for planned charitable donations. Investors who are regular charitable donors should make full use of all available benefits permitted by the tax laws.

Endnote

1. In reality, there is usually some co-movement between any two stocks in a portfolio, but this serves only to reduce, not eliminate, the benefits of diversification.

References

Constantinides, George M. 1983. “Capital Market Equilibrium with Personal Tax.” Econometrica 51, 3: 611–636.

Constantinides, George M. 1984. “Optimal Stock Trading with Personal Taxes: Implications for Prices and the Abnormal January Returns.” Journal of Financial Economics 13, 1: 65–89.

Dammon, Robert M., Kenneth B. Dunn, and Chester S. Spatt. 1989. “A Reexamination of the Value of Tax Options.” Review of Financial Studies 2, 3: 341–372.

Reichenstein, William. 2007. “Calculating After-Tax Allocation Is Key to Determining Risk, Returns, and Asset Location.” Journal of Financial Planning 20, 7: 44–53.