Journal of Financial Planning: April 2025

Edward F. McQuarrie is professor emeritus at the Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University. His research focuses on market history and retirement income planning; working papers can be found at https://ssrn.com/author=340720.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge the seminal work by Allan Roth on TIPS ladders and their application within the safe withdrawal rate literature.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION: Discuss this article with fellow FPA Members through FPA's Knowledge Circles.

FEEDBACK: If you have any questions or comments on this article, please contact the editor HERE.

NOTE: Click on the images below for PDF versions.

Existing strategies for decumulation can be grouped into two major categories: the life annuity, which pays out a fixed sum each year for life, versus a systematic approach to withdrawals, the best known of which is the 4 percent rule (Bengen 1994). Each of these approaches has important drawbacks.

I discussed problems with the life annuity in the December 2024 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning. Most notably, current annuity offerings in the United States do not adjust the payout for inflation. If inflation runs hot, the longer the client lives, the greater the erosion in the spending power of the annuity payout. That article showed how to hedge the annuity with a TIPS ladder to maintain real income, but had to acknowledge that the hedge could not be sustained for more than 30 years.

Bengen showed that in the United States, a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds had always been able to sustain 4 percent withdrawals, adjusted for inflation, for at least 30 years. However, the Bengen rule has not aged well. Pfau (2010) showed that it would have failed over and over again internationally, with failure defined as running out of money before the planned 30 years. McQuarrie (2025) showed that the 4 percent rule would have failed U.S. investors in the 1960s if transaction costs were included.

Few planners today find it useful to set a fixed and unvarying withdrawal rate like 4 percent. The field has moved toward systems of flexible withdrawals (Blanchett 2007, 2023). A flexible program of withdrawals can always be sustained, but to achieve that outcome, the client must be willing to decrease their withdrawals to what might be a very low level, especially after adjusting for inflation, and stick with that diminished income for as long as necessary. In short: under a flexible scheme, the money never runs out, but, same as the life annuity, spending power can drop a long way should market returns on the portfolio go through a bad stretch.

This article takes a different tack. It considers how a fixed rate of withdrawal on the order of Bengen’s 4 percent might yet be sustained for 30 years by drawing on a financial innovation not available when Bengen wrote in 1994. Roth (2022) has already shown how to arrange TIPS bonds in a ladder to sustain a fixed real rate of withdrawal—but only up to 30 years. This report goes further by showing how TIPS might provide the foundation for sustaining a fixed real rate of withdrawal for more than 30 years.

TIPS and TIPS Ladders

TIPS were introduced in 1997. These bonds, guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. Treasury, promise to return at maturity the inflation-adjusted value of the principal. During their term, they pay a coupon, with each coupon payment adjusted for inflation to that point. As the 30th anniversary of this financial innovation approaches, a TIPS bond is available for almost every year out through 2055.1

It is important to acknowledge that the expected real return on a nominal Treasury is roughly the same as on a TIPS; the nominal bond yield will be shaped by expectations for inflation over the course of its term, and its nominal yield will exceed the real yield on a comparable TIPS bond by about that expectation. Moreover, a long TIPS bond suffers the same duration risk as any other long Treasury, as some clients found to their consternation in 2022, when the negative impact of duration overcame the unexpected inflation of that year to produce a double-digit loss for TIPS ETFs and mutual funds.

Roth’s (2022) insight was to dispense with TIPS bond funds and instead to purchase individual TIPS ranging from one to 30 years in maturity and arranged in a ladder. For each future year, sufficient bonds are purchased maturing in that year such that, together with the coupon payments from all the unmatured bonds, a target sum can be realized. To maintain that targeted sum, the number of bonds bought at each subsequent maturity slowly increases, as fewer and fewer coupon payments get paid because of the declining number of bonds remaining. The result of this careful construction is a constant rate of real dollar withdrawals—precisely the outcome that can no longer be obtained from a life annuity, and an exact equivalent of what Bengen hoped to extract from returns on a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds.

In his proof of concept, Roth accepted the withdrawal rate that could be obtained based on TIPS yields in Fall 2022. This worked out to be somewhat more than 4.3 percent, rather better than Bengen felt could be promised using a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds, and far above the safe level of withdrawal determined by Anarkulova et al. (2023).

It has to be emphasized that withdrawals funded from a TIPS ladder are absolutely safe and pre-determined in real terms.2 It doesn’t matter how much duration risk is carried by the longer bonds in the ladder; these bonds will not be tapped until they mature, and their real value at maturity is guaranteed by the Treasury. The ladder holder is never forced to sell at the bottom in order to make their scheduled withdrawal for a year. That’s the beauty of a TIPS ladder, relative to the balanced stock and bond fund portfolios considered by Bengen, and an important advantage of the TIPS ladder over systems for flexible withdrawals.

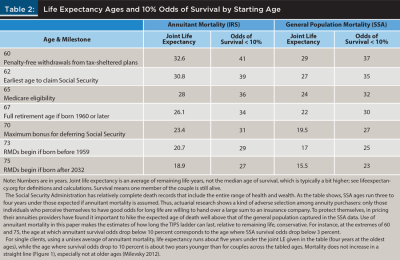

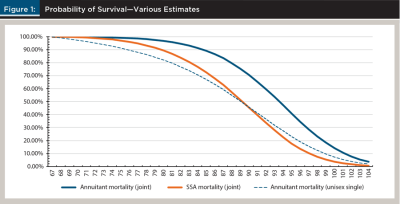

There remains one problem: no TIPS bond with a maturity greater than 30 years is on offer in the United States. The maximum length of a standard ladder is therefore limited to 30 years. That’s probably not enough today for a 65-year-old couple in good health; the IRS projects their joint life expectancy to be 28 years, with about a 50 percent probability that one member will survive past that date, and a 10 percent probability that one will still be alive after 36 years. Only a life annuity can provide income for an unlimited span bounded only by death. When a standard TIPS ladder reaches its end, the money is gone, even if life is not.

This article describes a hybrid structure founded on TIPS, focused on the goal of sustaining a fixed real withdrawal rate for longer than 30 years. Where McQuarrie (2024b) assumed the client would purchase a life annuity and then add TIPS as a hedge against inflation, this paper starts with TIPS and examines what might be accomplished without taking out a life annuity. Legacy outcomes are central to the analysis. The Achilles heel of the life annuity is that it lasts only for life, however short that life turns out to be. When life ends, the legacy value of the funds annuitized is zero.

The Strategy: TIPS Ladder Plus Side Fund

As noted, Roth (2022) accepted the 4.3 percent withdrawal rate afforded by the average yield across the TIPS maturity spectrum in Fall 2022, a bit more than 1.75 percent. The present effort begins with the question, “How much of the client’s $1 million would have been left over if their advisor had instead arranged the TIPS ladder to fund withdrawals of only and exactly 4.0 percent for the 30 years?” If withdrawals at 4.0 percent are accepted as adequate when 4.3 percent could have been obtained, then there will be a surplus.3

The general formula for the amount required for the ladder is [1 – (required withdrawal rate / TIPS funded rate)], where the TIPS funded rate represents the withdrawal rate if all the funds available were placed in the ladder. For example, with 4.00 percent / 4.31 percent, the set aside amount works out to 7.2 percent, or $72,000 on $1 million, with only $928,000 having to be put into the ladder to get an initial withdrawal of $40,000.4

If TIPS were issued with maturities greater than 30 years, then the adviser could have promised the client almost 32 years of 4.0 percent withdrawals, given TIPS yields at the time ($72,000 / $40,000 = 1.8 years). But no such 31-year or 32-year maturity is offered on TIPS in the United States. The $72,000 surplus must be invested some other way.

Two possibilities are explored: either heavy up on the 30-year TIPS to fund later withdrawals or invest the surplus in some other asset. The criterion for success will be an extension that reasonably hedges against longevity. “Reasonable” will be defined as extending the ladder to an age where there is only a 10 percent chance that one member of a married couple will still be alive when the ladder runs out. That translates to 36 years for a 65-year-old couple, and a rather shorter span for clients in their early and mid-70s, as developed below. Put another way, success will mean a ladder extension that takes the survivor out to about age 101.

Translating TIPS Yields Into Withdrawal Rates

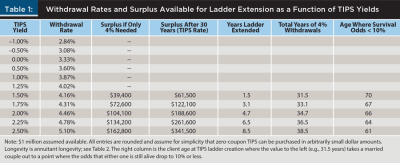

The yield on TIPS fluctuates with interest rates and with current inflation expectations. TIPS yields were more than high enough to fund 4 percent withdrawals in late 2022 when Roth wrote, but that need not always be the case. Table 1 looks at the sustainable real withdrawal rate that can be achieved across various levels of TIPS yields for periods of 30 years. The top end of the yield range, at 2.5 percent, corresponds to TIPS yields seen briefly in early Fall 2023 and late in 2024. Practically speaking, it approximates a best-case scenario. The negative yields at the bottom of the range were seen after the pandemic in 2020 and 2021 and were also approached in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–09. Future yields could go lower still, but these values provide a plausible worst-case scenario.

Table 1 makes it apparent there is a large range of plausible TIPS yields—anything below 1.25 percent—that cannot support a withdrawal rate of 4 percent over 30 years. Hence, the strategy described in this report will not always be available. Planners perform a service to their clients by keeping track of when TIPS yields are high enough to make the strategy effective.

Ladder Extension Using TIPS

The simplest and arguably the safest approach to ladder extension is to heavy up on the 30-year TIPS issue, using all the surplus to purchase extra amounts of this issue beyond what was required for the ladder. An extra $40,000 placed in the 30-year TIPS guarantees that the real equivalent of $40,000 will be available at the end of 30 years,5 thus funding the required 4 percent withdrawal for another year.

Table 1 shows the number of years the ladder can be extended for each level of surplus on the assumption that, 30 years out, TIPS with a yield of at least 0.0 percent are available over the stated term.6 To the right, the final column incorporates information from the life expectancies given in Table 2. It shows the client age at which the available surplus, funding that much extension, takes the ladder to the point where the odds are 10 percent or less that either member of the couple is still alive.7

Here are two illustrations drawn from Table 1. Consider the case where TIPS yields are a relatively favorable 1.75 percent. About $72,000 in surplus will be available in this case. Assume the 30-year TIPS yields the same as the average yield across the curve. Invested at 1.75 percent, that $72,000 will produce a real $122,100 30 years hence. Harvesting that invested surplus will extend the ladder three more years. In turn, a married couple age 67 has only a 10 percent chance of having a survivor after 33 years, when they would be 100.

To take a more favorable case, suppose the TIPS yield is 2.25 percent, a level frequently touched in 2024, albeit on the high side historically. That will produce a surplus of $134,200, which, invested at 2.25 percent, will give $261,600 in 30 years, funding the ladder for over six extra years, making it suitable for a 64-year-old couple as it provides withdrawals out to about age 101, where the odds are less than 10 percent that one of them will still be alive.

It is important not to stop with life expectancy in evaluating ladder extension strategies. Obviously, about half of clients will still have a surviving member after joint life expectancy is reached. A ladder that runs out at life expectancy will thus fail many clients. And mortality is not linear, as can be seen from Figure 1, which shows various estimates for the odds of survival at each age through 110. The “odds < 10 percent” metric is arbitrary, but usefully supplements the life expectancy estimates, in showing just how long a TIPS ladder must be extended if it is to offer a competitive alternative to a life annuity.

Summary

Table 1 shows that ladder extensions will often be feasible. When TIPS yields are adequate, more than 1.5 percent, it is a simple matter to extend a TIPS ladder past 30 years by purchasing extra amounts of the 30-year TIPS bond. For clients well into their 60s, and at more favorable yields, the ladder can be extended to the point where the odds are less than 10 percent that either of the clients will still be alive. These extensions using TIPS are almost as guaranteed as the base ladder itself.8

However, somewhat younger clients, and clients generally when TIPS yields are only moderate, may require a longer extension than can realistically be provided by extra purchases of the 30-year TIPS. A second alternative for ladder extension provides a potential solution.

Ladder Extension with Stocks

Planners may be familiar with Jeremy Siegel’s book, Stocks for the Long Run, initially published in 1994 and now in its 6th edition (Siegel 2022). Siegel analyzed U.S. stock returns from 1802 to the present, drawing on multiple sources, and found that over those two centuries, U.S. stocks had returned between 6 percent and 7 percent after inflation. However, Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton (2024), looking at about two dozen markets outside the United States and measured back to 1900, found lower real returns on international stocks, closer to 4.5 percent.

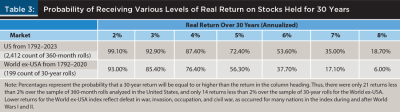

As any planner schooled in the Bengen tradition will recognize, the most important fact is not the average return but the range of returns likely to be experienced over the holding period of interest. McQuarrie (2024a), who updated Siegel’s work by compiling a broader and more complete sample of 19th century U.S. returns from primary sources, also computed 30-year rolls. In the most recent iteration, McQuarrie looked at 360-month rolls beginning with January 1793 to January 1813, through the roll ending December 2023, or 2,412 of these 360-month rolls in all. This sample allows determination of the probability that holding a broad stock index fund for 30 years will produce a real return of any given level, and also, the plausible range of returns that might be expected over 30-year holding periods—i.e., the maximum length of a TIPS ladder without extensions.

Using a sample from Global Financial Data, McQuarrie (2024a) also computed 30-year rolls on the GFD World ex-USA index, beginning with the roll from December 1792–December 1822, through rolls ending December 2020 (these rolls were annual rather than monthly). This analysis provides an out-of-sample test for the U.S. experience, which was characterized by very favorable outcomes in the century after World War I, when the United States assumed the role of global hegemon. The international sample gives some sense of returns received by investors in ordinary nations that were not blessed with the success enjoyed by investors in the United States, providing a chastening perspective, were U.S. markets not to continue to be favored by history.

Table 3 shows the probability of receiving a given real return, in the United States or in the World ex-USA, over a 30-year span. In the United States, 2 percent real returns were about the floor, with only 21 rolls out of 2,412 recording a lower return. Perhaps more importantly, these sub-2 percent returns were clustered at two points: during and before the Civil War, and in the 1930s. In other words, outside of a terrible conflict that rent the nation or a Great Depression, U.S. stock investors have always compounded their wealth at better than 2 percent real returns per year over 30-year periods. That favorable experience does not have to continue, of course. But it can be used to set reasonable expectations for a stock investment intended to extend a TIPS ladder.

Turning to the international record, the story is not quite so positive. Only 93 percent of 199 rolls showed a return greater than 2 percent. But here again, the sub-2 percent returns are clustered in one period. All 14 were booked for rolls ending 1919–1932—the aftermath of the Great War, as it was then called. The other 185 rolls, beginning with the 30 years ending 1822, all saw real returns greater than 2.0 percent.

Here the planner needs to be prepared for a heart-to-heart talk with their more risk-averse clients. Stocks are always risky. By definition, the worst market return in the historical record had never been seen before that point. Just because the U.S. stock market has never suffered a real decline over 30 years—as the World ex-USA index in fact did for rolls ending in 1920, at minus 0.64 percent—is no reason such a decline cannot occur over precisely this client’s time horizon. If the client expresses deep misgivings that an investment in a broad stock market index can’t really be expected to have a healthy return over 30 years, then this ladder extension strategy is closed to them. They must take whatever extension can be squeezed from the TIPS yield curve of the time, as discussed above.

Only clients with some appetite for risk can attempt a ladder extension using stocks. Accordingly, a 3 percent real return will be taken as the lowest reasonable floor on a 30-year stock investment intended to extend a TIPS ladder. That return was exceeded in 93 percent of U.S. rolls, and again, all the shortfalls were associated with the Civil War and the Great Depression. The next question is the highest real return on stocks that can reasonably be expected over 30 years. That would appear to be 6 percent, which has been exceeded just over half the time in the United States, and which is close to the geometric mean of the entire 231-year U.S. stock market record. The international record confirms that 6 percent real is at the high end of expectations; outside the United States, fewer than 40 percent of rolls recorded a return that high.

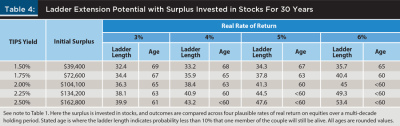

With boundaries of 3 percent to 6 percent set on stock market real returns, Table 4 examines how long a 30-year TIPS ladder might be extended, as a joint function of the surplus generated from TIPS yields above 1.5 percent, and the level of stock market return to be expected when that surplus is invested for 30 years.

To begin, consider a modest surplus, as expected from TIPS yields about 1.75 percent, and a very conservative assumption for stock returns, of 3 percent real. That should fund a 4.4-year extension, and 34.4 years will take a couple as young as 67 out to the 10 percent survival age. That is only modestly better than could have been achieved with an extra allocation to the 30-year TIPS. The power of compounding does not amount to much at low rates of return such as 3 percent, even over a period as long as 30 years.

Next, consider a more favorable circumstance, where TIPS yields are at 2.25 percent, as in much of 2024, and stock returns are projected at 5 percent, as seen in about 70 percent of U.S. rolls historically. This produces a dramatically stronger outcome: an extension of 17.6 years, or a ladder of 47.6 years in all, more than adequate even for a couple as young as 60 years old. And that outcome may be an under-estimate; it assumes that all the stock investment, about $700,000 real, out in 2055, will be sold and placed in TIPS bonds maturing over the following 17.6 years and yielding 0.0 percent. If TIPS have positive yields in 2055, or if the stock portfolio is only slowly run off, then the extension may cover 20 years or more.

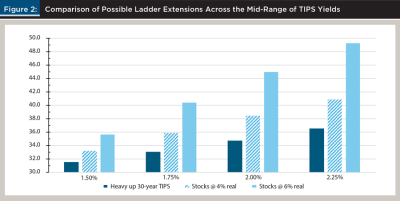

Summary

Figure 2 brings together the range of possibilities for ladder extension, from the minimal amounts to be expected from modest TIPS yields with the small surplus placed in 30-year TIPS, to the much more substantial extensions possible when TIPS yields are on the high side and a larger surplus is placed in stocks delivering moderate to high returns. At the left end of the chart, for younger ages near 60, a life annuity remains competitive, especially for clients with a great fear of longevity who can imagine themselves requiring payments through age 105 or beyond, an age that will not be reached by most TIPS ladders despite extension. But these clients should be cautioned about the likely effect of inflation on nominal annuity payments 40 years out.9 At the right side of the chart, for clients in their upper 60s or older who are not very risk averse, it is hard to see how nominal annuity payments can compete with an extended TIPS ladder, especially given the greater counterparty risk on top of the vulnerability of fixed payments to inflation. In fact, when TIPS yields are high and the clients are over 70, planners might even explore a shorter ladder of 25 years and a withdrawal rate of 4.5 percent or even 5 percent, which will still leave some surplus for an investment in stocks, which give a high likelihood of extending even that shorter 25-year span out to an age where the odds of survival are less than 10 percent.

As the last example shows, there is nothing magical about either a 4 percent withdrawal rate or the 30-year span; these values were adopted to connect with the Bengen literature on safe withdrawal rates. The formula was deliberately stated in general terms: whenever [(desired withdrawal rate / TIPS funded rate) < 1], there will be a surplus available for investment. Both the desired withdrawal rate and the span of the ladder should be part of the planner’s conversation with clients. The tables in this article show the planner how to construct an illustration for any desired combination of the two and how to project a range of outcomes when the surplus is invested in stock.

Legacy Considerations

All affluent clients who enter the decumulation phase must decide the importance of legacy. The poles among the alternatives are to maximize income while alive, without regard for whether any money is left behind for others upon their eventual demise, or to satisfice income now, unlocking a surplus that can fund some amount of legacy. The life annuity encapsulates the first pole. During 2024, when TIPS yields fluctuated between about 1.9 percent and 2.5 percent, SPIA payouts fluctuated around 7.5 percent to 8 percent of the principal for couples in their early 70s—much higher than the 4.5 percent to 4.75 percent withdrawal rate that a 30-year TIPS ladder with no extension could fund (Table 1). But the legacy potential for an SPIA, once any guarantee period lapses, is always zero.

The ladder extension strategies considered in this article epitomize the second pole. When TIPS yields are favorable and could fund a real withdrawal rate of more than 4 percent, then accepting only 4 percent produces a surplus that can be invested elsewhere; and of course, the ladder itself is drawn down at the rate of only 4 percent real the first year and through each subsequent year. If joint demise occurs after 10 years and a day (following the lapse of the most common guarantee on a life annuity), the legacy from the TIPS ladder alone will be about 65 percent of the starting value, even as the legacy from the life annuity goes to zero.

To extend a ladder past 30 years, for most couples in their upper 60s or older, means enabling withdrawals to an age where 90 percent of couples will have passed away. That was the threshold set for success: an age where the odds were 10 percent or less that a survivor would remain. A joint demise prior to the end of the extended ladder necessarily creates a legacy and, reversing the logic, some such legacy is likely in 90 percent of cases for the starting ages given in Tables 1 and 4.

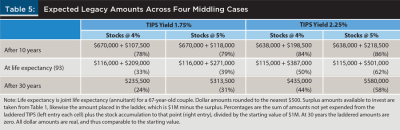

That legacy is likely to be greater when the surplus is invested in stocks intended to be held for 30 years. Table 5 was constructed to give planner and client a feel for the size of the legacy that might result. Because the permutations of possible outcomes are very numerous, only selected middle cases are included. These cases span TIPS yields of 1.75 percent or 2.25 percent and stock returns of 4 percent or 5 percent. Clients are considered to be in the middle of the age range considered in this paper, at 67, giving them an (annuitant) joint life expectancy of 93. For these cases, legacy amounts are estimated at 10 years, at life expectancy and at 30 years upon the ladder’s exhaustion. The dollar amount of the surplus at the time the ladder is set up is taken from Table 1. The legacy dollars are expressed in real terms and split into funds remaining in the TIPS ladder versus stock wealth accumulated to that point. Their sum is expressed as a percentage of the starting value of $1 million.

At 10 years, legacy amounts range from 78 percent of the starting sum at the low end, to 86 percent on the high end, or $860,000 (real) on the running example of $1 million. At life expectancy of 93, after having sustained real payouts for well over two decades, legacy dollars are of course much reduced but still range from 33 percent of the starting value to 62 percent. At 30 years, when the ladder is exhausted, only stock wealth remains, but this is still 24 percent to 58 percent of the starting sum.

Again, all the amounts in Table 5 are in real dollars. If inflation ran at 3.5 percent over those 30 years (per the historical average rate in the United States since 1934), then the dollars given in the bottom row of Table 5 can be multiplied by about 2.8 to get nominal values. In the best of these middle cases, where TIPS yields of 2.25 percent generated a substantial surplus to start, the client would have maintained a real withdrawal rate of 4 percent for 30 years, while still having available for legacy purposes (or ladder extension) more nominal dollars than they had at the outset.

Finally, although the preceding discussion has been pitched in terms of legacy, the same analysis shows the amounts available in what might be called residual funds, available to address late-in-life emergencies. Sometimes, before death can intervene, clients may be subject to unexpected and substantial costs, most notably medical expenses not reimbursable under Medicare, expenses for assisted living, and nursing home expenses. No such reserve is available upon annuitization, except as taken from other funds. Rather, the signal advantage of a life annuity is the acceleration of income it confers, without fear of exhaustion while alive. Where the TIPS ladder generated $40,000 (real) for a couple, a life annuity, given a reasonable crediting rate of 5 percent would, at the 21-year joint life expectancy of a 73-year-old couple, provide a (nominal) payment of about $78,000, almost twice as great as the initial income from the TIPS ladder (in the early years, before inflation begins to bite). But the money annuitized is all gone; nothing remains for unexpected expenses except the ongoing payments.

The planner renders a valuable service by helping clients think through these various aspects of decumulation. There is no one right answer; the issues are as complicated as the needs and desires of the human beings who must weigh their options for decumulation and decide the importance of legacy (Statman 2024).

Conclusion

Planners face two general options when advising clients on how to decumulate savings. They can recommend some form of life annuity or propose a systematic approach to regular withdrawals. The annuity is simple: once and done. Payments are fixed and guaranteed for life on the credit of the insurance company. There are no further decisions to be made. As originally conceived by Bengen (1994), systematic withdrawals were also simple and fixed: historical tests showed that an initial withdrawal of 4 percent, adjusted for inflation each year, taken against a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds, had always been safe and sustainable over a period of 30 years.

When the Bengen historical test foundered under further examination by Pfau (2010) and Anarkulova et al. (2023), withdrawals ceased to be simple. Any rate that could be deemed safe historically was achingly low and starved the client of income they could probably have enjoyed, even as it would have produced a hefty legacy in most historical cases. In the decumulation space, that defines an ineffective strategy: too little income while alive, too much left over at death.

Accordingly, strategists focused on withdrawals gradually abandoned the quest for a safe fixed rate in favor of more flexible strategies in which withdrawals could be dynamically increased or decreased (Pfau 2019), providing more income in the go-go years while lowering the risk of premature exhaustion of funds (Blanchett 2014, 2023). The price of this new set of solutions was complexity and the accompanying fees to manage this more complex process. There can be no once-and-done under a system of variable withdrawals. Success, defined as never running out of money, is made likely by a system of rules and checkpoints, but the program must be monitored continually.

Planners need to appreciate that the advent of TIPS has fundamentally changed the available options for withdrawal strategies. Most important, the prospect of a safe, fixed withdrawal strategy has reemerged, with a guarantee stronger than any private insurance firm can offer, and more certainty than a portfolio of risk assets could ever provide. The TIPS ladder offers the simplicity of a life annuity with a reasonable prospect of leaving some legacy, even as a substantial real income can be secured for decades, extending well past life expectancy. Just two elements are required for success: TIPS yields must be high enough—generally, above 1.5 percent across the curve—and the client must be satisfied with an income of about 4 percent of the amount placed in the ladder.

These two requirements also highlight the limits of the TIPS strategy. First, it won’t always be available, as in 2020–2021 when TIPS yields were far too low. Second, either a life annuity or a flexible withdrawal strategy will almost always be able to provide more (nominal) income in the initial years. The annuity liquidates principal to achieve an initial withdrawal rate on the order of 7.5 percent to 8 percent. The TIPS ladder at 4 percent will catch up in real terms after a dozen years or so (McQuarrie 2024b), but not all clients will want to eschew the higher initial payments. Flexible withdrawal strategies can often promise initial rates of 5 percent or 6 percent nominal, again accelerating income into the go-go years, but cannot guarantee the duration and consistency of that rate nor any given level of real income, as they remain hostage to market returns.

In conclusion, this article shows the planner how to implement an extended TIPS ladder that can rival the life annuity in terms of handling longevity risk, even as it guarantees more safety and certainty than any program of flexible withdrawals from a portfolio of risk assets.

Endnotes

- There is currently a gap between January 2035 and February 2040, consequent to the Treasury having shifted from 30-year issues to 20-year issues and back again. I ignore that gap in this treatment.

- Absent nuclear disaster and similar catastrophes in which the full faith and credit of the United States Treasury would no longer avail.

- For an alternative formulation, see Stocker (2022).

- The TIPS funded rate can be estimated from the PMT or similar spreadsheet formula, entering the average real yield across the TIPS curve. Thus, PMT(1.75 percent, 30, $1,000,000) results in $43,100, just under the 4.36 percent rate booked in Roth (2022), while PMT(1.75 percent, 30, $928,000) results in $40,000 (rounded), or 4 percent. Numbers in the paper use the PMT formula and are idealized; actual results for any real-world ladder, given heterogenous coupons, uneven spacing of maturities, and gaps in issuance, will vary by a few basis points, on average, and across individual years.

- Or somewhat more, if a positive real yield is available; see examples below.

- If short TIPS in 2055 yield a negative 1 percent, as seen several times after 2010, a real equivalent of only $39,600 will be available after a year. If a surplus sufficient to fund three years was set aside, payouts would be a real $39,600, $39,204, and $38,812. The count of years given in the table is thus overstated if TIPS yield less than 0 percent and understated if TIPS in 2055 yield more than 0 percent, with the effect most visible for longer extensions of five or more years.

- Measured in terms of life expectancy for annuitants. Life expectancy for the general population tends to be lower; see note to Table 2.

- Almost, because the yield on TIPS of any particular maturity, three decades from now, cannot be predicted. See note 6 above for a numerical example.

- Figure 2 in McQuarrie (2024b) tells the sorry tale.

References

Anarkulova, A., S. Cederburg, M. S. O’Doherty, and R. W. Sias. 2023. “The Safe Withdrawal Rate: Evidence from a Broad Sample of Developed Markets.” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4227132 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4227132.

Bengen, W. P. 1994. “Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial Planning 7 (4): 171–80.

Blanchett, D. 2007. “Dynamic Allocation Strategies for Distribution Portfolios: Determining the Optimal Distribution Glide Path.” Journal of Financial Planning 20 (12): 68–81.

Blanchett, D. 2014. “Exploring the Retirement Consumption Puzzle.” Journal of Financial Planning 27 (5): 34.

Blanchett, D. 2023. “Redefining the Optimal Retirement Income Strategy.” Financial Analysts Journal 79 (1): 5–16.

Dimson, E., P. Marsh, and M. Staunton. 2024. Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2024. Zurich: UBS AG.

McQuarrie, E. F. 2024a. “Stocks for the Long Run? Sometimes Yes, Sometimes No.” Financial Analysts Journal 80 (1).

McQuarrie, E. F. 2024b. “Help Clients Hedge Their Life Annuity with TIPS.” Journal of Financial Planning 37 (12): 78–90.

McQuarrie, E. F. 2025. “How the 4% Rule Would Have Failed in the 1960s: Reflections on the Folly of Fixed Rate Withdrawals.” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5126013 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5126013.

Milevsky, M. A. 2012. The 7 Most Important Equations for Your Retirement. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Pfau, W. D. 2010. “An International Perspective on Safe Withdrawal Rates from Retirement Savings: The Demise of the 4 Percent Rule?” Journal of Financial Planning 23 (12): 52–61.

Pfau, W. D. 2019. Safety-First Retirement Planning. Virginia: Retirement Researcher Media.

Roth, A. 2022, October 24. “The 4% Rule Just Became a Whole Lot Easier.” Advisor Perspectives.

Siegel, J. J. 2022. Stocks for the Long Run. 6th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

Statman, M. 2024. A Wealth of Well-Being: A Holistic Approach to Behavioral Finance. New York: Wiley.

Stocker, A. 2022. “Using Inflation-Linked Bond Ladders to Increase Retirement Portfolio Survivabi